May’s darkest comedy stands as her best and most daring film

Elaine May is one of the greatest filmmakers and comedic minds that America has ever been blessed with. Yet up until even a few years ago, the majority of people who knew her name would have considered such a statement to be, at least somewhat, outrageous. May began her career in improv comedy, finding success in the late 1950s by partnering with Mike Nichols, another soon-to-be filmmaker. Their comedy albums as Nichols and May reached the Billboard Top 40 and won Grammy awards; they accrued wild acclaim while their act transformed from buzzed-about comedy club performances to sold-out shows on Broadway. They split up in 1962 at the height of their popularity. To this day, they are recognized as figureheads in the history of modern comedy.

May’s career as a filmmaker was another story entirely. Her ex-improv partner came out hot as a director with the Oscar-winning hits Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and The Graduate (1967). Following his early success, Nichols’ film career had many ups-and-downs. He nonetheless worked within the studio system until his death in 2014. May, on the other hand, made four brilliant films, but her life behind the camera was plagued by conflict and discrimination. From her directorial debut, A New Leaf (1971), onward, she had regular creative and financial battles with producers, who were quick to stick her with a reputation for being difficult. With the exception of the Neil Simon-penned The Heartbreak Kid (1972), her films as a director were unsuccessful at the box-office. Her narratives, which focus largely on conniving, self-centered, and childish men — one plots to marry and murder a rich woman for an inheritance (A New Leaf), another falls in love with a beautiful college girl while on his honeymoon (The Heartbreak Kid) — were far from surefire crowdpleasers. When the financial letdowns mixed with her determination to stand up for herself as an artist, May was forced into extreme and desperate situations. She held footage hostage as a last ditch effort to maintain final cut privileges and, eventually, had to rely on favors from powerful friends to secure jobs after she was blackballed from Hollywood.

May’s final narrative film cast her reputation in stone for most moviegoers. It’s a not-so-little movie called Ishtar (1987), the strange and epic tale of two bozo nightclub performers (Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman) who become mixed up in Cold War espionage while attempting to work in Morocco. The film was cursed before it even reached theaters. The budget ballooned out of proportion, deadlines were not met, and rumors of May’s supposedly odd behavior on set spread like wildfire throughout the industry. Ishtar received historically negative press, leading many to believe the studio was trying to sabotage its own film. All of this led the movie to be one of the biggest box office and critical disasters of the Heaven’s Gate (1980) decade. It became known as a notoriously bad movie despite most people not even knowing what it was about. May has joked, “If all of the people who hate Ishtar had seen it, I would be a rich woman today.”

Of course, many of the best things in life take the longest time to be appreciated. The world is slowly coming to recognize Ishtar’s peculiar brilliance, and with home video releases available for all of May’s films, minus — frustratingly enough — The Heartbreak Kid, her work has never been as accessible and/or as beloved. The respect now being shown to her singular and challenging oeuvre is long overdue and has been hard earned. The promise of a potential upcoming film is news that even mainstream publications seem excited for.

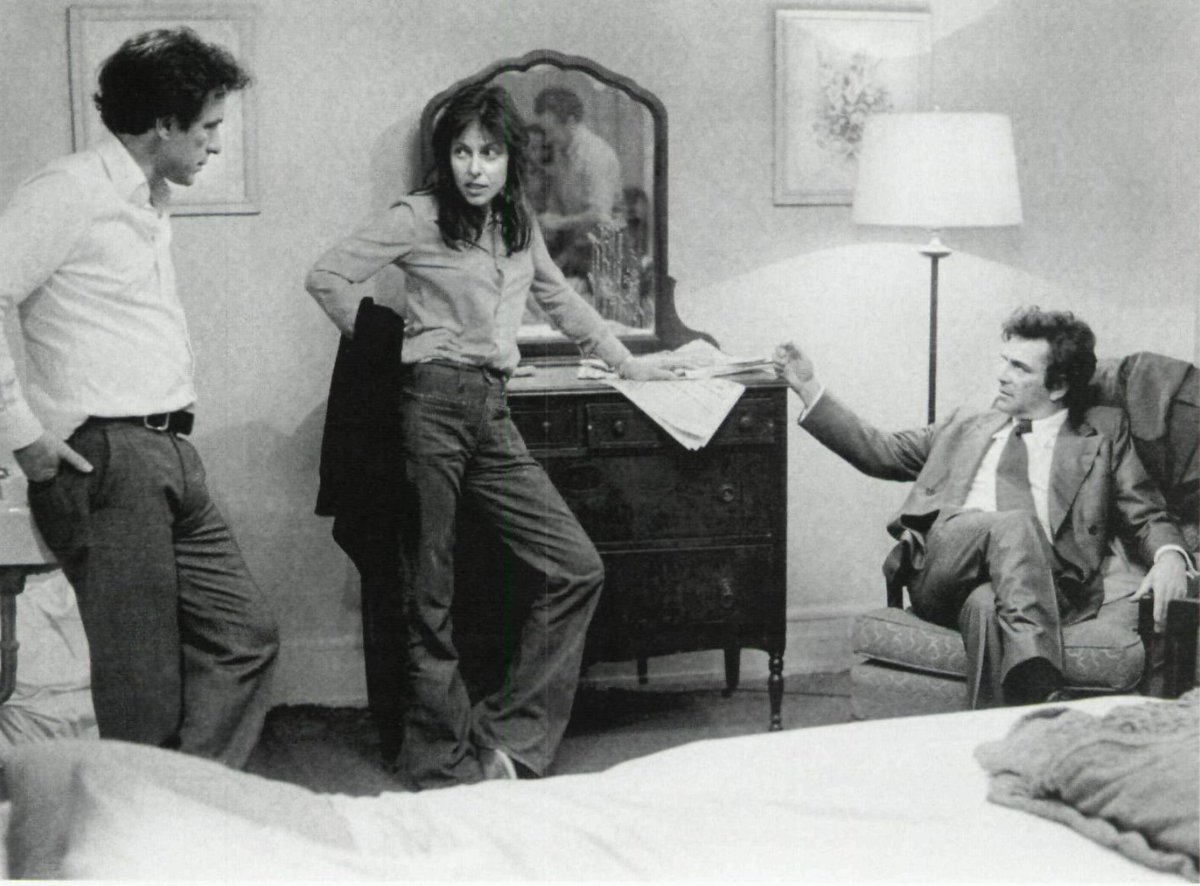

Mikey and Nicky (1976) is May’s best, and darkest, comedy. She began writing the script in the 1950s when she was a member of The Compass Players in Chicago. Based upon stories she heard while growing up in a family with mob connections in Philadelphia, Mikey and Nicky begins with a low-level gangster, Nicky (John Cassavetes), hiding out in a hotel room. He has received word that a contract is out on his life. He calls his oldest friend, Mikey (Peter Falk), for help while a hitman (Ned Beatty) searches the city for him. Mikey tells Nicky he will help him get out of town, but he holds lifelong grudges against his childhood friend and is secretly working with the hitman.

While it may not always feel like it, Mikey and Nicky is about love in its most extreme and confounding states. The film’s exploration of its central friendship dares to get very ugly. The mens’ night together is filled with as much affection and nostalgia as it is with mind games, paranoia, and jealousy. May sends us on a thousand journeys of spiritual reckoning as Mikey and Nicky wrestle with their perceptions of themselves, each other, and their complicated history together. She orchestrates each moment to tune viewers into the microscopic details being shared between her characters and she doesn’t let up on us until her film and their relationship have reached their ends.

Critics often discuss Mikey and Nicky within the context of a gangster film. But to focus on the strictures of genre with a work as wild as this only impedes one’s ability to recognize just how daring May’s film is. Even the grittiest gangster movies have a slickness about them. Think of those luscious slow-mo tracking shots washed over with neon in Mean Streets or how pristinely scripted Reservoir Dogs is. Sure, there’s more blood, profanity, and cruelty — and in the case of Mean Streets, a narrative rooted in its director’s personal, lived experience — but more than anything, these films are R-rated updates beholden to most of the same genre conventions established in the 1930s. May uses the gangster elements in her film to much different ends.

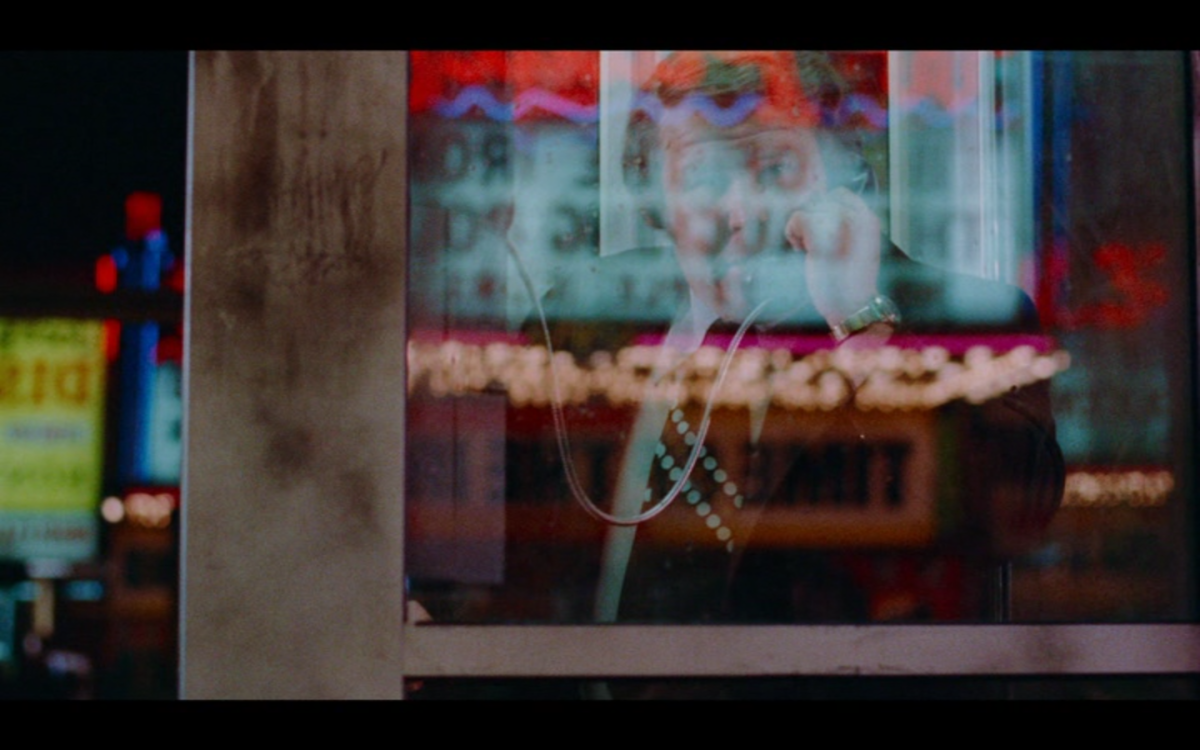

For one thing, nothing is slick about Mikey and Nicky. May’s vision is devoid of flashy tommy gun shootouts and backstreet romance; absent are the mythic dimensions of stars like Bogart or Cagney. Her characters might be connected to organized crime, but they are not movie gangsters. Nicky has a devilish charm about him, but May is more inclined to show him suffering from ulcers and bickering with old women on city buses. Ned Beatty’s hitman is clearly a professional, but he spends most of the night driving around lost and struggling to find parking. The climactic fist fight consists of Mikey and Nicky slipping on wet streets and failing to land their punches. May is more interested in watching her characters wriggle around in strange and humiliating social interactions than she is in the film’s mafia plot. In scripting the film, she ditched all notions of traditional gangster narratives for a more episodic and freewheeling structure that allowed her more freedom to explore with her actors. In showing her characters at their most petty and befuddled, May gives us what we lose with most movie gangsters: her gangsters are still real people. They know the myths and how they are supposed to act, but they are dangerous in a different way because they are so unpredictable and don’t follow the usual mobster script.

Within her unjustly small filmography, May’s filmmaking is at its strongest when she shows her roots as an improv comic. Like in her stage act with Nichols, in which audience members were often asked to suggest styles of famous literary icons to guide the duo’s improvisations, she is most powerful when she has something — another filmmaker’s style, a genre, or a specific narrative structure — to work against or build from within her films. She first did this in The Heartbreak Kid with its many allusions to Nichols’ The Graduate. Ishtar is modeled after the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby “Road” movies. Mikey and Nicky (its title believed to be another sly reference to Nichols) is her distortion of a gangster movie, but the film’s style is more crucially related to the films of star John Cassavetes.

Just to clarify, I am not suggesting that May’s films are in any way reductive or spoofs or merely “commenting on” these other works, especially as all of the above mentioned films were made by male artists or rooted in historically masculine genres. I want to highlight that May herself is encouraging her audience to make these comparisons.1 As if being one of the only female writer-directors of her time in Hollywood wasn’t enough, she fought to produce provocative works from within the studio system that stood as challenges to both long-held Hollywood traditions and the most up-to-date contemporary fashions of her era. Even when films like A New Leaf or Mikey and Nicky were taken away to be recut and tamed by the studios, they retained their particular satirical bite. But notice how May’s films go beyond satire by expanding, pushing further, and in nearly every case surpassing the above mentioned works by more popular or established artists (Nichols’ The Graduate and Simon’s Heartbreak Kid screenplay) or genres (the Hope and Crosby road movies and the gangster film) in terms of emotional complexity, aggressive social commentary, and dramatic risk taking.

The most overt displays of this tendency show throughout scenes in The Heartbreak Kid, which are clearly in conversation with Nichols and The Graduate. After they disbanded as a comedy duo, May and Nichols remained constant sources of inspiration for each other. But May often went a step further than sharing screenplay drafts for consultation or borrowing old improv gags: She appears to have brought aspects of their personal relationship and creative dynamic into her work. Part of what made their partnership so successful was that they were truly opposites. In their stage act, Nichols says, “Elaine would fill sketches, and I would shape them.” Nichols was a noted perfectionist, a polisher who would fine-tune every little detail and phrasing, especially once they landed on Broadway and had to refine most of their act to a repeatable set of dialogue. May wanted every performance to be fresh. She was interested in pushing herself and her collaborator into unknown territory and seeing what would happen.2 These divergent traits from their live performances translated into each of their filmmaking styles.

As examples, let’s take scenes from each film in which the lead male character must make a troubling confession to his romantic partner: In The Graduate, Benjamin (Dustin Hoffman) admits to his new love interest Elaine (Katharine Ross) that he has been having an affair with her mother (Anne Bancroft); In The Heartbreak Kid, Lenny (Charles Grodin) tells his wife, Lila (Jeannie Berlin, May’s daughter), that he has fallen in love with someone else on their honeymoon and wants a divorce. These scenes demonstrate the differences in May’s and Nichols’ styles, but also May’s willingness to dive into the roughness of her characters’ most brutally emotional moments in ways that most other films avoid.

Related: An Artist’s Nightmare: John Cassavetes, Horror Films And The Incubus by Brett Wright

In The Graduate, Nichols approaches his scene through an almost entirely visual presentation. His style is very cool — in 1967, critics were calling it “European.” The scene, as with the rest of the film, is staged entirely from Benjamin’s perspective. His confession takes place through a series of close-ups of the characters’ faces, yet most of the expressive work relating to their emotions and understanding of what is going on is done through camera work, eyeline matches, and character blocking. Elaine comes to understand what Benjamin is telling her through little more than a shifted glance as Ben looks from Elaine to her mother who stands behind her after mentioning “that older woman.” The blocking lines everything up so that when Elaine follows Benjamin’s gaze, the process of her realization can be charted beat-for-beat visually. All viewers have to do is connect the dots by way of a rack focus shot to Mrs. Robinson when Elaine turns to look at her in the background. This is then followed by a slow reversal of the focus shift, racking back to Elaine’s eyes welled with tears in close-up. The camera’s literal change in focus signifies that Benjamin’s meaning is becoming clear to Elaine. There is a purity to Nichols’ approach. It is beautifully done and the emotions are clearly conveyed, but in seeking such an efficient means of translating this devastating scene and what takes place between these characters, it comes off very clean for such a messy situation.

May’s Heartbreak Kid scene is built in the exact opposite fashion. May’s primary interest is in her actors’ performances. She keeps the camera at a distance, but only to create room to bring more perspectives into the scene. She holds within unrelenting long takes as Lenny fails to find an easy way of telling his new wife that he wants a divorce. She lets her characters squirm, not out of cruelty, but out of a fascination with what will rise to their surfaces as they struggle to articulate themselves. May stages the scene so that Lenny has to keep finding new ways of approaching the topic as he hesitates to speak directly to his wife. The date-night setting of a busy seafood restaurant plays a crucial part in the scene as well, causing Lila to misinterpret many of Lenny’s statements as romantic compliments, when he is actually trying to convince her that she will be fine without him when he leaves. The crowded restaurant also allows outside influences to impede upon Lenny’s focus. May builds layers and tangents into the interaction between the couple: Lenny stalls for time by throwing a tantrum over a slice of pecan pie, berates the waitstaff, and draws more and more attention from surrounding diners with his antics. Unlike Benjamin, Lenny must continually strive to regain control of the scene as he fails to be direct with his wife. He eventually blurts it all out. Compared to Lila, The Graduate’s Elaine has it easy — Lila is so shocked and confused by Lenny’s confession that she can barely breathe. Her panic then sends Lenny into unfortunate efforts to try and calm her down. This is mostly in order to quell her from “making a scene” but he’s also oddly caring in a way that only Charles Grodin could muster.

Unlike Nichols’ streamlined visual approach to The Graduate, May feeds on the chaos and the lack of understanding between her characters. For May, the emotions they are feeling and trying to convey or process cannot be neatly expressed through choreographed glances or virtuosic camera moves. Nichols’ approach is mannered and controlled in the style that became prevalent in many mid-to-late ’60s studio films. May, on the other hand, ruffles everything up. There is danger in her style.

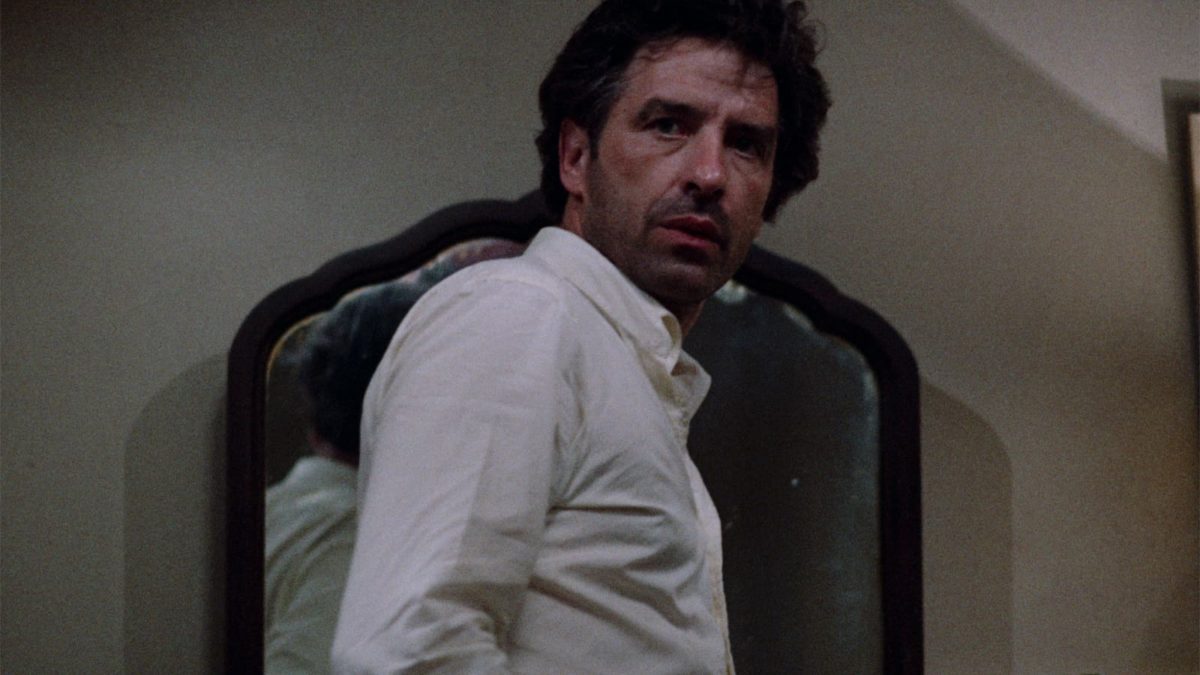

In Mikey and Nicky, Cassavetes seems to be the creative foil that May held of the highest regard. With Nichols, May was more interested in ribbing him through her films or joyfully one-upping him with more daring explorations of similar scenarios. In working with Cassavetes on Mikey and Nicky, she found a collaborator who would follow her where Nichols might not have. Like May, Cassavetes was another uncompromising force — in his everyday life and behind the camera. Within his own films, he offered his collaborators opportunities to join him in undertakings of profound self-exploration. For actors, working on a Cassavetes film was not about escaping into a character, but bringing yourself to the work, warts and all. His productions could last for years. He would shoot unbelievable amounts of footage and revise and retune his edits until he had explored every facet and every possible emotion within each scene. It is easy to see how his approach would be attractive to May, especially for a project she held as dear to her heart as Mikey and Nicky.

Cassavetes and Falk joined May’s production while A Woman Under the Influence was being edited in late 1973. They both worked with May on the script, but, in the words of the film’s producer Michael Hausman, Mikey and Nicky was “like a personal, private movie” between May and Cassavetes. Cassavetes was not only a creative collaborator, but stood by May when the production ran wildly over schedule and budget. According to Marshall Fine’s biography of Cassavetes, Accidental Genius (2005), he even stepped in to direct second unit photography when the production was at its most hectic, notably riding alongside Ned Beatty to shoot portions of his driving sequences. As her manager Jack Rollins said about her approach to live comedy, “Elaine would go on forever if you let her… She had no sense of when to quit.” His words hit on that restless urge to create that made her one of the world’s most innovative improv artists while also recognizing the habits that would later get her in trouble with profit-minded film studios. While making Mikey and Nicky, she famously kept cameras rolling well after her actors had left the set and shot three times more film than Gone with the Wind. Post-production went on for so long due to her indecisiveness while editing that Paramount took away her right to final cut. This is what led May to steal some of the footage and hide it until she reached an agreement with the studio. Unfortunately, this only caused further conflict and resulted in the film being cobbled together and released carelessly in a sloppy cut for Christmas 1976. May later bought the film back from Paramount in 1978 and re-edited Mikey and Nicky herself into the highly acclaimed version that is now available.

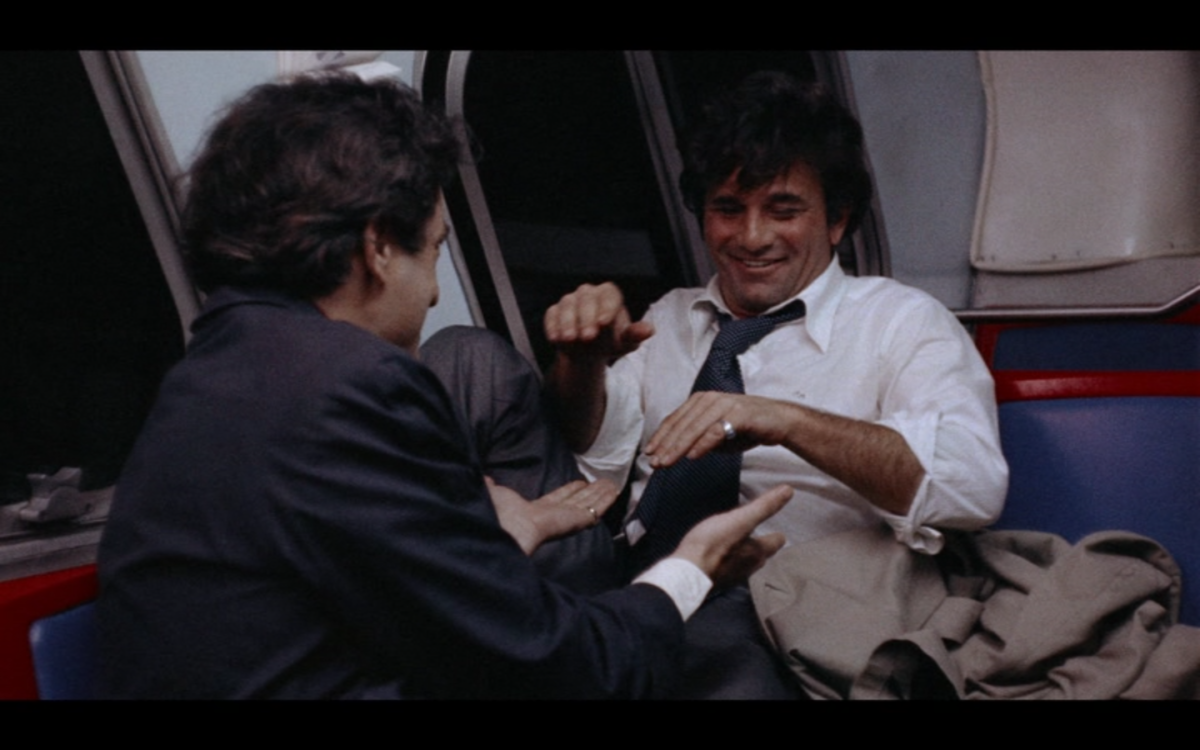

For anyone who knows Cassavetes’ own work up until Mikey and Nicky, many scenes in May’s film will feel familiar. For example, when Nicky tries picking up an African American woman in a bar and gets into an altercation with her boyfriend, one may recall a nearly identical, yet much briefer and far less severe encounter in Minnie and Moskowitz (1971); An extended sequence of the title characters sparring over Nicky’s mistress echoes back to the business men vying for the attention of Gena Rowlands’ call girl character in Faces (1968); and there are many scenes of Cassavetes and Falk running around and roughhousing in the streets like their characters do with Ben Gazzara in Husbands (1970).3 Casting Cassavetes himself in the film builds another layer of meaning upon what May is creating. It is fascinating to watch her direct him in scenes that resemble aspects of his own work that were so closely tied to his own personality and life experience. The public antics of Moskowitz (played by Seymour Cassel) are recognized as a form of self-portraiture from his days courting Gena Rowlands; the often petty and defensive businessmen in Faces share many of their creator’s greatest insecurities. It is no surprise that, under May’s direction, Nicky is the character that some consider to be the closest of Cassavetes’ own acting performances to what he was often like in real life.4

Like Shadows (1959) or Faces, Mikey and Nicky is deeply concerned with where identity and performance meet. May’s characters are constantly putting on acts and trading them out for each new audience or obstacle they encounter. Being lifelong friends, her small-time gangsters harbor deep-seated grudges and personal jealousies and they play against each other’s most private insecurities. As Ray Carney writes in American Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the American Experience (1985), Mikey and Nicky “use their considerable powers of performance not as vehicles, however imperfect, of self-exploration and tentative self-expression… but as strategies of self-concealment and self-protection.” They know exactly where to strike to get the reaction they want as their egos flare up and burnout in disturbing and often childish displays of emotional violence. May’s most inspired use of gangster film elements is in how her characters’ awareness of their roles as gangsters creates conflict within their interpersonal relationships. They try to act the part of cool, thick-skinned mafia men but the world keeps getting in the way. They slip between personas — tough guys, childish victims, buddy-buddy lifelong friends — on a dime, but the rate at which they switch them out feels more defensive than anything.

Their attempts at self-protection also take the form of self-deceptions: They trick themselves, putting on the most vicious acts to quell their own demons or bounce back from moments of vulnerability to build themselves up against each other. This is never more apparent than when outsiders are brought into their interactions, most notably women. Towards the end of the film, Nicky takes Mikey to see his mistress, Nellie (Carol Grace). He talks crudely about her, like anyone can seduce her with ease. When they arrive, Nellie proves to be gentle and thoughtful, completely unlike the picture Nicky painted for Mikey. She holds conversations about current events and respectfully fights off Nicky’s advances. That’s when he starts acting up. At this point, Cassavetes’ performance becomes its most intricately layered and kaleidoscopic: He begins his seduction like a frat boy, gleefully touching her and sneaking kisses. When this doesn’t work, he starts guilting her into showing him affection, before he shifts gears again into smothering her with lovey-dovey talk. Cassavetes moves and mixes his demeanor from charming to threatening to pathetic to cruel so swiftly that the distinctions blur. He eventually gets his way and makes love to her in front of a bewildered Mikey, who has been reduced to a third wheel. But Nicky’s performance isn’t over. Once he finishes, he urges Mikey into the room for his turn with Nellie. Mikey dopily accepts before failing in front of his friend, lashing out against her with reprehensible violence, and struggling through his own mess of humiliation and anger.

From the description of this scene, one might imagine these characters to be entirely repulsive — even unwatchable — due to their behavior. But May’s depiction of these self-centered, neurotic, and narcissistic men show them not to be just abrasive, but pained, ugly, vulnerable, and unstable in ways that plunge through to their core. Through the female characters, May confronts Mikey and Nicky with various challenges to drop their acts. Their later interactions with their wives (Rose Arrick and Joyce Van Patten) add further dimensions to the personas they cultivate for themselves and put on for each other. As night turns to morning, details about their home lives and the intimate bonds they have bragged about sharing with family are shown to be more fragile and illusory than they make them out to be. We see them desperate, even violent, for connection, while also unable to reconcile the gaps in their understanding of how they are perceived by their significant others. The moments Mikey and Nicky spend alone with their wives in the final act are just as, if not more, devastating than the death that ends the film. May doesn’t show either of the men coming to revelations of themselves or trying to really communicate with their wives, particularly Mikey as he deals with the shocking end of his longest friendship. Instead, she creates a sense that new acts are in the making: personal histories being rewritten, motivations being refined, and new characters forming from the wreckage.

Purchase Mikey and Nicky on Blu-ray/DVD here

Stream Mikey and Nicky on The Criterion Channel or Amazon

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)

- Richard Brody mentions one occasion where May explicitly stated it was her point for such a connection to be drawn in a 2016 appreciation of Ishtar. Regarding the genesis of the film and its multifaceted political intentions, he writes, “[May] said that she was inspired by a viewing of one of the ‘Road’ movies, starring Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, and that her original plan was to call the movie ‘The Road to Ishtar.’ Beatty was the one who wouldn’t allow the title, she said, because he worried that ‘they’ll compare us to Hope and Crosby.’ But that, May said, was exactly the point.”

- The quote from Nichols and many of the other details regarding Nichol’s and May’s stage act are sourced from Mark Harris’ 2021 biography, Mike Nichols: A Life, which grants some incredible insight into the duo’s approaches to comedy and art through interviews with Nichols, May, their manager Jack Rollins, and others who they shared the stage with.

- One might also notice that Mikey’s son is named Harry, the name of Gazzara’s character in Husbands. I have never read anything that supports this, but considering May’s tendency, or else consistent luck in having divine coincidence, to make jokes of characters’ names (beyond the Mike Nichols reference of the title, perhaps the slyest joke in the film is that Ned Beatty’s hitman is named “Warren,” though May only lists the character’s surname in the credits) it wouldn’t be farfetched to imagine her paying tribute to the only missing member of the Husbands trio by giving his name to a five year-old child.

- For a more detailed discussion of Cassavetes’ personality and similarities to the character of Nicky, see Ray Carney’s Cassavetes on Cassavetes (2001).