Prince stepped into the mouth of evil when he recorded The Black Album in 1987. A divine vision yanked him back out and the forbidden masterpiece has been shelved ever since

Ah, yes: the Dark Funk. It’s one of the great lost albums, and though it’s on Tidal and was briefly available in 1994, it’s, for the most part, still pretty lost. Even with Prince’s death opening up a trove of archival goodies, the reissue campaign has so far amounted to an expanded Purple Rain and a bunch of his Piano & A Microphone shit. Maybe that’s because all the really hardcore fans already have The Black Album. I got mine on Mediafire, that treasure trove of sketchy rarities whose loss was a crushing blow to everyone outside the music industry. But who wouldn’t want to hear “Bob George” on vinyl? Have three decades dulled the mystique of this forbidden masterpiece? Or is this thing just too damn evil to safely unleash on mere mortals? Would a vinyl pressing lead to a Ghostbusters-style plague, with little green things swooping around and stealing our hot dogs?

Prince might have suspected as much. The album, originally titled The Funk Bible, was recorded in 1987 but pulled and bulldozed a week before release, purportedly because Prince — while on Ecstasy pills that may have been provided by Anthony Kiedis — experienced a divine vision that informed him it was evil. He replaced it with Lovesexy, a solid album that’s just about the polar opposite of The Black Album. This event was the first of a series of blows for the Purple One that derailed his muse, with the ascent of hip-hop and his escalating woes with Warner Bros. being no less cataclysmic. The Black Album is arguably the last great album he recorded, coming after Sign O’ The Times and before the Graffiti Bridge and Batman soundtracks and his depressing descent into new jack swing.

Part of the The Black Album’s appeal is that it sounds forbidden. When I first stumbled across it in 2010 or 2011, still licking my wounds from that god-awful fake Cosmogramma and that Best Coast rip that was just a bunch of Seinfeld audio, I thought it might be a fake-out. “Is that your boyfriend? Huh! I don’t care!” he sniffs on “Le Grind.” The Purple One, a shy guy who likes to be seduced, is typically above such macho bullishness. Even once you’ve heard the industrial steel-trap funk of songs like “Housequake” and “Good Love,” The Black Album still feels like it scuttled in from somewhere else besides the psychedelic wonderland of Paisley Park. It’s so much darker and more disgusting than we’re used to. And so, so, so much funnier. Prince doesn’t get nearly enough credit for his sense of humor, probably because The Black Album still isn’t widely available.

Prince flipped through fashions and personas freely while remaining resolutely himself — or at least retaining vestiges of a sort of bedrock Prince persona. The Black Album sounds so uncanny because that bedrock is gone. We don’t get a lot of the tender, slightly dorky romantic with his head in the clouds. There’s no depth to this Prince, no turmoil between his sexual appetites and his desire to walk the righteous path, no conflict between his stammering neuroses and the sexy situations he seems to stumble into around every corner. He’s a deranged master of ceremonies, and when he wants he can be a Casanova (“Le Grind”), a cocky rapper (“Dead On It”), a gun-toting cuckold (“Bob George”), a mad scientist cackling beneath bolts of lightning (“Superfunkycalifragisexy”), a parody of his perception as the skinny motherfucker with the high voice (“When 2 Are In Love”).

Prince conceived The Black Album at least in part as a response to critics who charged he was too pop and too “white,” probably after the ridiculous Francophile fantasia of his Under the Cherry Moon film and accompanying Parade album. On no Prince album is the singer more self-aware of his effeminacy, his smallness, his status as one of the last great glam poppets. Most of the album is sung in his trembling low voice rather than his famous falsetto. The pitched-down protagonist of “Bob George” clearly sees Prince as an affront to his masculinity, leading to a great “ain’t that a bitch” pun. “When 2 R In Love,” so sincere on Lovesexy, here sounds like a parody of his own baby-making ballads (“the speed of their hips can be faster than a runaway tray-ay-ain”). It’s a cloud of steam in the middle of the Black Album’s polluted miasma, but it’s less a reprieve than another dirty joke.

No other Prince album is quite like this — none dance with the devil anywhere near as salaciously as this blazing lump of coal from hell.

It’s hard to say if the nods to hip-hop on The Black Album owe to a sincere effort to connect with listeners who were tuning into that music or simply Prince’s paranoia at potentially being replaced. “Dead On It” initially seems like a mean-spirited hip-hop parody — the equivalent of Marge Simpson rapping at Bart to discourage him from going to a 50 Cent show. “See, the rapper’s problem stems from him being tone-deaf,” he explains, as if gesturing at a PowerPoint. But the song features more than a few lines Lil Wayne would have cackled in ecstasy to have written: “Got a gold tooth, cost more than a house!” he flexes; “Got diamond rings on four fingers, each one the size of a mouse!” Maybe Prince is just such a good writer he can’t even make fun of rap without producing a great rap song. But he also carves out space for backing singer Cat to rap — badly — on “Cindy C.”

“Cindy C” is one of Prince’s creepiest songs, centered on his unrequited crush on supermodel Cindy Crawford, she of the beauty mark. On an album that blurs the line between irony and sincerity, this is the trickiest song to parse. Is it scaly Serge Gainsbourg-style horndoggery, unwholesomely objectifying a real person on a public platform? Is it a sequel to “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” an illustration of how useless the Prince character is at actually initiating romantic relationships? Was she in on the joke? “Come play with me, Cindy!” shrieks Prince. “Okay, uh… just a minute!” says a busy-sounding female voice. “WHY WON’T YOU PLAY WITH ME?!? AAAAAAAAAAAAAH!” replies Prince. It certainly sounds like a self-deprecating joke, but there’s still the ugly fact that Prince’s response to Crawford turning down his advances at a party was to pen an ode to her “furry melting thing.”

Sex seems a little less fun on this album than in most of his music. On “Rock Hard In A Funky Place,” his erection is a burden, and it’s only when he’s about to put it to use that he goes limp. On “Superfunkycalifragisexy,” he espouses the joy of squirrel meat as an aphrodisiac, inviting us to let him tie us to a chair and kiss his blood-stained mouth. Prince has always been kinky, but what he describes here is more primal than mere S&M. Unusually in his discography, The Black Album is about what he does to her, not what she does to him, and it’s telling Prince slips into a sort of puppet show when he’s writing these songs. This music isn’t about Prince but a greater truth of funk, a genre whose name springs from the strong odors of the body. This is a disgusting album, every bit as gross as There’s A Riot Goin’ On or the sweatiest stinkholes of the George Clinton catalog.

Perhaps to prove he has more to offer than a sweet falsetto, Prince pushes his voice into extremes of lopsided, psychedelic sewer-sludge. The exhortations on “Superfunkycalifragisexy” come from deep within his gut, and though opening songs with orgasmic bursts of soul noise is a common Prince trick, few are more deranged than the maniacal laughter that opens that song, or the petulant cry of penile pain that introduces “Rock Hard In A Funky Place” (pitch-shifted up, per his Camille persona). Even on “Cindy C” his falsetto feels grannyish, psittacine, a tough squawk designed for scrabbling over galvanized funk rather than the gentle birdsong of his ballads. He sounds a lot more masculine than usual, perhaps understanding the era of the bad-boy rapper and R&B star was soon to be upon us; at least he gives non-binary folks a refreshingly sincere shoutout on “Le Grind.”

The music, likewise, is light on the Blade Runner synth mist of Sign O’ The Times and miles away from the coquettish parlor pop of his latter Revolution records. This is a meat-and-potatoes funk album rendered in metallic, almost industrial tones, a machine so well-oiled the nuts and bolts slide right out. Prince’s beloved Linn LM-1 drum machine sounds like nothing more than the march of a marauding killer robot on songs like “Dead On It” and “Bob George,” and like the Bob George character, it’s pitch-shifted down, taking on its own dark-side alter-ego. This is funk, so chord changes are a luxury, but “Bob George” is rendered in a sparse twelve-bar blues that makes it even more frightening, situating it within the murder-ballad tradition as the song’s protagonist shoots up a bunch of cops and threatens the man who’s stolen his girlfriend (“I’ll kick your ass. Twice!”).

In a poem in the program for his 1988 Lovesexy tour, Prince claimed he was possessed by a malevolent spirit he called “Spooky Electric.” Given how often he evoked technology in his theology — remember the “de-elevator” from “Let’s Go Crazy” and the “dance electric” from “God” — it’s not hard to interpret this as a reference to Satan. No wonder he was so scared. Prince was a long way from the “Freak in the Pulpit” of his final years, but his religious songs shudder with awe. “4 The Tears In Your Eyes” and “God,” on which he pantomimed the birth of the universe through maternal screams, aren’t evangelical tracts but prayers from a speck on the wind who really seemed to fear the man upstairs. They’re a little like the koans of Brian Wilson’s Smile, which was likewise shelved after the reclusive, drug-blinded Beach Boys genius decided his music was somehow evil.

When Wilson finally completed Smile in 2004 and released the sessions in 2011, fans responded with adulation and glee. The missing piece of the puzzle was finally complete. So why is The Black Album largely unknown except to the reverent Prince fans, despite being the follow-up to a record widely regarded as Prince’s masterpiece and the final statement of one of the most untouchable runs in pop history? If I had to take a gander, I’d guess it’s that Wilson had a reputation as a genius with not much to show for it. You had to squint a little to hear a lot of the brilliance of the early Beach Boys singles, and it seems odd that they’d jump straight from Pet Sounds to paranoid late-’60s albums like Smiley Smile. The Brian Wilson story needs a climax, a towering explosion of genius to cement the beach bard as one of the preeminent auteurs of the psychedelic era.

If so much of what typically makes him great is absent here, the things that make The Black Album great — its black comedy, the depths of its sonic depravity, the thrill of hearing Prince behave so un-royally — are unique to it.

Prince, on the other hand, is one of the most frustratingly prolific of all pop stars. He released no less than 39 albums in his lifetime, and that’s not counting bootlegs, aborted projects, tour exclusives and all the shit still hiding in the Vault. Had The Black Album never been made, Prince’s reputation would still be secure. Sign O’ The Times — a flawed, sprawling, messy masterpiece — would serve as a perfect coda to his herculean peak. The Black Album isn’t a conclusion but a diversion. Prince was stepping into the mouth of evil, and a divine vision yanked him back out into another direction. No other Prince album is quite like this, save perhaps the bizarre Gold Experience from 1995 — by no coincidence the best album of the last quarter-century of his career — and that album doesn’t dance with the devil anywhere near as salaciously as this blazing lump of coal from hell.

I still have that same Mediafire rip of The Black Album eight years later, and it’s my go-to when I want to put on a Prince album — especially around friends, many of whom don’t care for Prince. Either they’re turned off by the ’80s gated-drum sound he pioneered or they’re daunted by the size of his discography. I suspect that, as many of them are straight men, some of them are simply turned off by the anti-manliness of Prince’s music and persona. There aren’t a lot of out-and-out queens on the charts right now, straight or otherwise, which is why I love the current crop of flamboyant rappers like Young Thug (whose guttural glossolalia isn’t far from what we hear on “Superfunkycalifragisexy”) or A$AP Rocky (who uses a pitch-shift effect a lot like on “Bob George”). Those artists at least temper their music with conventional masculinity, as if holding up an “I’m not gay!!!” sign.

Everyone I know responds positively to The Black Album, even while greeting my personal favorite 1999 with a disinterested shrug, and it makes me think Prince was right about this thing’s commercial prospects. This is a Prince album so markedly divergent from the pervasive cultural prejudices surrounding the singer that it’s probably the best album to play for people who don’t like him — that and Purple Rain, and The Black Album is so much more interesting. We don’t think of Prince as violent or twisted or deranged. We certainly don’t think of him as funny. Maybe we don’t even think of him as that funky. Compared to something like Funkadelic’s first two albums or even the Red Hot Chili Peppers, most of Prince’s stuff sounds almost vanilla. His music is (appropriately) Apollonian for a genre for which the body is the endgame and feral instinct is expected to prevail over logic.

This is a Prince album so markedly divergent from the pervasive cultural prejudices surrounding the singer that it’s probably the best album to play for people who don’t like him.

And hell, maybe The Black Album won’t seem that evil to you. It’s not that much filthier than mainstream pop albums like Beyoncé’s self-titled or Rihanna’s Talk That Talk. Maybe the album’s true evil is in its betrayal of Prince’s values. This is one of pop’s most idiosyncratic figures, a man nearly as synonymous as Bowie with flying your freak flag, consciously changing who he is to court an audience that might dismiss him because of his eccentricities. This is the fairy queen as black-clad avenger, the cerebral studio auteur as dancefloor dumbass. And it’s one of his best albums. If so much of what typically makes him great is absent here, the things that make The Black Album great — its black comedy, the depths of its sonic depravity, the thrill of hearing Prince behave so un-royally — are unique to it.

We love artists who think outside the box, but a greater challenge yet is to find a box and be as creative as possible within its confines. And when Prince finds a box, he fills it and splashes against its sides like the ocean against the shore. And Purple Rain, which will probably forever be his most beloved album, was the soundtrack to a Hollywood star vehicle; could there be anything more baldly commercial? The Black Album was made for compromised reasons. It was a response to baseless criticism. It was an attempt to appeal to young, hip, black music consumers who might have seen him as an embarrassing relic of a disappearing decade as their ears tuned to a chartscape that was mutating to make room for rap. But somewhere in the process of making an album for the kids, Prince let Spooky Electric take over and drag the kids down to hell with him.

Follow Daniel on Twitter

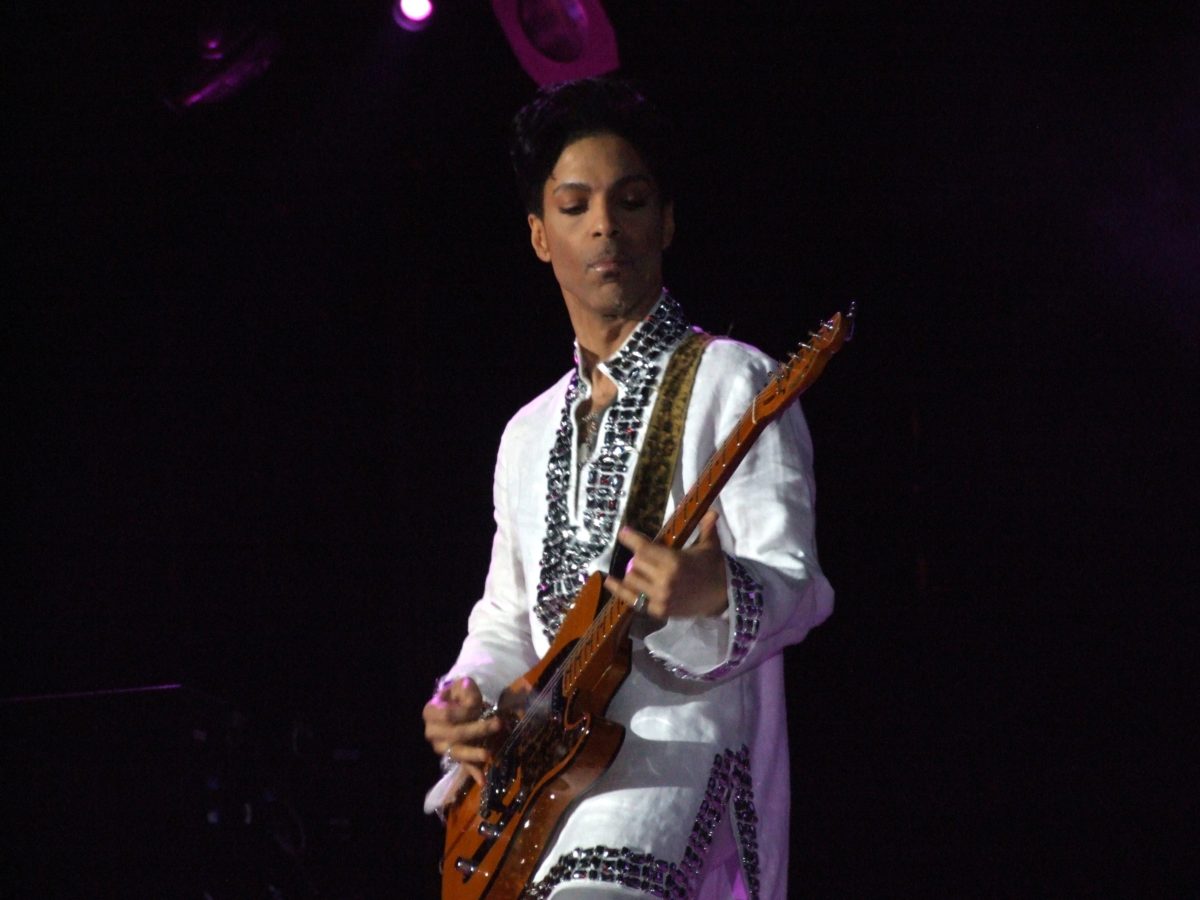

Feature image: Johnny Silvercloud/Flickr

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)