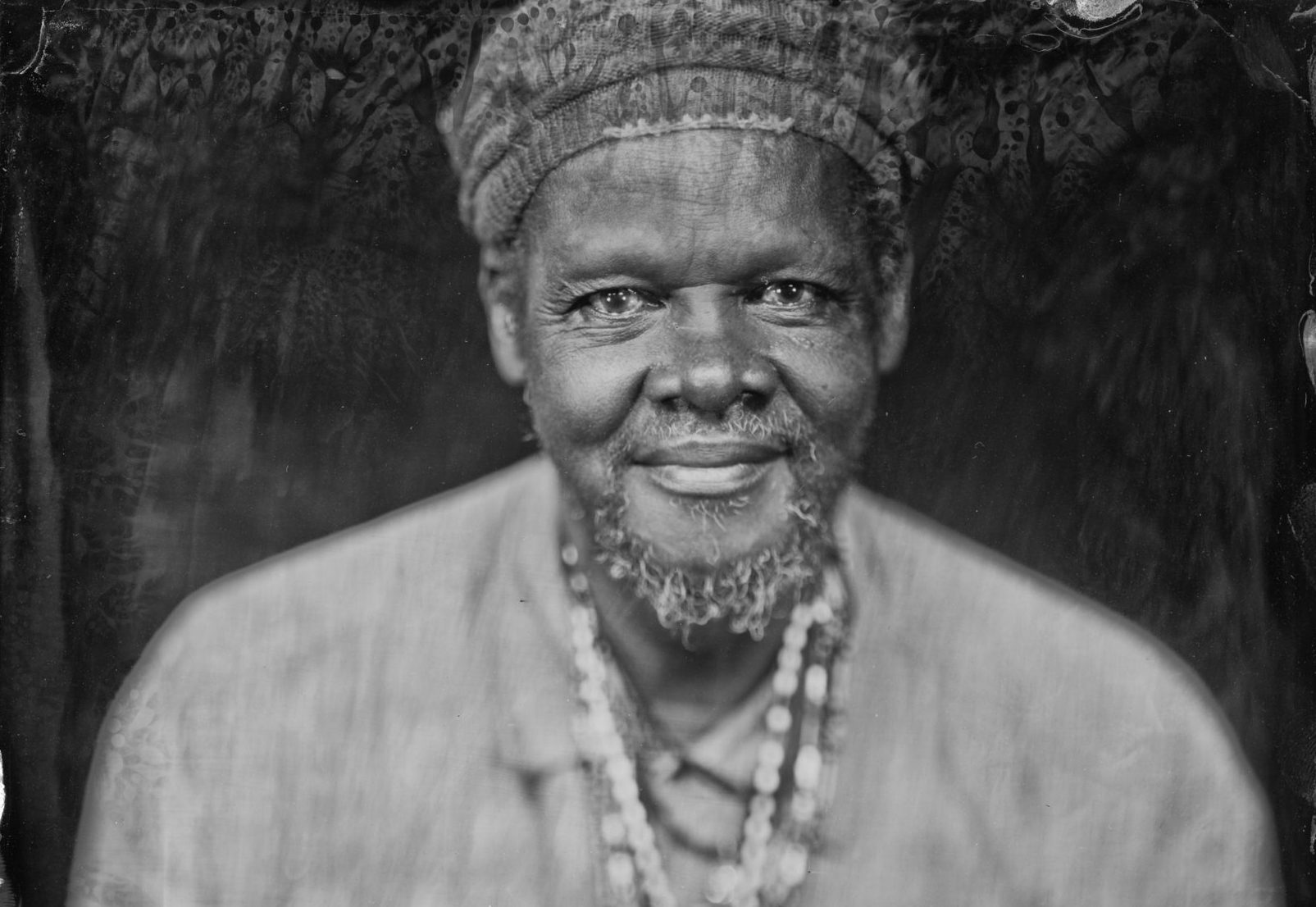

Lonnie Holley is one of the most unlikely heroes in indie-rock circles. He’s a 68-year-old African-American artist born in Jim Crow Alabama. He didn’t make his first album until age 62. His lyrics are almost entirely stream-of-consciousness, and he never performs the same song the same way twice. His band consists of himself on vocals and keys, backed by a trombonist and drummer. He eschews what most people would think of as song structure. His voice is untrained at best, and he never stops singing. And he’s collaborated with Bon Iver and members of Deerhunter and the Black Lips; toured with Bill Callahan and Animal Collective; contributed several interludes to an Arthur Russell tribute album and recently inked a deal with Jagjaguwar, known for indie heroes like Okkervil River.

It’s easy to be skeptical, reminded of the aging bluesmen trotted out by shady promoters before leering white audiences during the ’60s folk revival. But the differences are that Holley has more creative control than just about any other artist you could care to name — he’s unbound even by the restrictions of playing the same song twice — and he’s spent decades as an internationally-renowned artist with complete creative control: just not for music. His monumental sculptures, often made from trash, have been a fixture of the American art world since the 1980s and were displayed in the White House under President Clinton.

He’d been making music all that time in private, but encouraged by art collector Matt Arnett and Lance Ledbetter of reissue label Dust-to-Digital, he started releasing new recordings early this decade. Just Before Music (2012) and Keeping A Record Of It (2013) came out on Ledbetter’s label to modest acclaim; this year’s MITH, a humanistic lament for America, is one of 2018’s best records.

Holley will headline the 15th anniversary celebration of Mississippi Records with a performance at Portland’s Hollywood Theater on Monday, Dec. 3. Toody Cole (Dead Moon, Pierced Arrows, The Rats, Range Rats) will perform with a surprise band, following renowned songwriters Michael Hurley and Ural Thomas. Fresh off a tour of Europe, Holley answered a few of our questions via email.

You’ve been writing songs for decades but only recently decided to take up a recording career. Why did it take so long?

Lonnie Holley: I was focused on making art. I didn’t really think about music from the studio. It was something I was doing for private comfort. But once I started thinking about sharing it with other people, and me hearing it played back, I got excited about sharing it.

Do you feel like the press, audiences, etc. focus too much on your life story and not enough on your art?

In the past, I think that maybe that was true. But I understand why it fascinates some people. How many people are the 7th of their mama’s 27 children from 32 pregnancies? How many children got taken away from their mama’s and traveled with a burlesque dancer? How many young children grew up in whiskey houses and was entertained by the state fair and a drive-in theater in their backyard? How many young people were locked up for no reason when they were barely 11 and basically lived like a slave for four years? In the 1960s in America? I don’t think the answer to any of those questions is a big number. And here I am having lived all of that. And then to take all of those things I’ve encountered and become an artist who has art in museums all over the country, I recently saw online where someone commented and said, “I wonder how much of that story really happened to him?” And I thought, “Man, I wish some of it hadn’t happened.” But then realized that all of that stuff was what led me to be who I am today. And I wouldn’t want or wish my life on anyone else, but it was the life that happened to me. And I appreciate it and am grateful for it.

You play a lot of shows and collaborate with indie rock artists whose audiences are chiefly younger, white fans with a background in rock and who might not normally be exposed to improvised music by a 68-year-old African-American artist. Do you feel like these audiences appreciate or understand your work?

I do. My band and I just played a bunch of shows this summer with Animal Collective, and their audience was so appreciative. They gave us standing ovations every night. And I noticed that the Animal Collective guys, who were so nice to us, would often stand by the stage and watch a lot of our set. Matt [Arnett] is always having to tell me about the people we are playing with. I don’t know if those audiences have always understood what I was doing or not, but they sure acted nice either way. I remember some nights when we would start a show, Dan [Lanois] would come out and introduce me. I wasn’t as well-known then, and I’m sure it helped get people to focus and listen. That meant a lot to me. If there was ever anything I could do for Dan, I’d do it. But I feel that way about Bradford and Bill Callahan and everyone else, too. When Bill had his baby, I sent him a painting to welcome his child into the world.

How do you typically record a song? I understand your work is largely improvised, but the arrangements on MITH are very rich — are the other musicians improvising? Are there a lot of overdubs?

The songs are always improvised. But it isn’t made up. It’s real for me. If you ask me to tell you about my breakfast, I’m going to improvise my answer because I wasn’t expecting it, but I’m not making up what I had for breakfast. The eggs were real. And so was that delicious Dutch cheese.

The other musicians I’m working with are also improvising, though they have an idea about what idea I’m trying to share. On the recordings, usually we do the first take, where I play a keyboard and sing. If I’m recording with collaborators, I like to play live with them. Then, often immediately, I’ll lay one more layer over the top, generally on another keyboard and another vocal. Then be done. Sometimes I want something that isn’t there and I have to get it added later. But not usually. Dave (Nelson) did that on “Suspect” from the record. I really wanted his trombone on that song, but he wasn’t with me in Porto. So we added it later.

Your songs are rarely, if ever, the same twice. How easy is it to perform them in the studio vs. on a large stage?

They are never the same twice. I’ve never tried to make them the same but don’t think I’d even want to. Matt mentioned to me the other day that I did some version of “I Woke Up in a Fucked-Up America” 15 or 20 times in 2017 and 2018, but after the video came out this summer, I haven’t played a version since. I might yet still. But I have been singing a song called “Send Help! I’m in America,” which feels like the next step. More people now realize that a lot of us have been waking up in a fucked-up America, some for a long time. Now it’s time to send help.

You use the word “humans” to describe what most of us would call “people” throughout MITH. Why do you prefer this word?

I’ve always used that word because we are all part of humanity in this universe. I use the word “brain” instead of “mind,” too, because I hope others can learn to appreciate the power of our brains. When I got hit by a car when I was 7, the doctors said “the boy is brain-dead.” Well, I’m not brain-dead, and since then I’ve wanted to give credit to the brain.

In “I Woke Up In A Fucked-Up America” you mention “computer-misusing.” How do you feel the Information Age has changed the world for the better? For the worse?

For someone like me, who wasn’t able to go to school, I’ve learned so much from the Internet beyond the classroom. But we can become too dependent on technology to the point that we don’t know how to do anything anymore. I learned so much from being down in the ditches and the creeks and walking the roads and taking things apart and putting them back together. If a young me had had that technology, I may not have appreciated all that I appreciate. I call her Cold Titty Mama. The CTM. Computer Technology Management. We have to learn how to use her because she surely isn’t going to nourish us. She’s cold and gives no milk.

What goes through your mind when you sit down to write a song?

Well, I don’t write songs exactly. My life has prepared me for my songs. And for my art. You asked earlier about people focusing on my life story, but the truth is if you understand my life story a little, you will probably understand my art or my music a little better.

I have a million memories. And visions of things that haven’t happened yet. And I’m really interested in science. And the planets and the solar system. I try to understand how everything works. I had to teach myself to read and to write because I never really got a chance to go to school. I’d say I create songs but don’t write them. No song is ever the same, even if I tried to sing the same song.

Do you listen to much music? If so, what do you listen to?

I listen to a lot of music. I listen to a lot of my own music that hasn’t ever been released. But I love oldies. The stuff I grew up on. I love all music. From Stevie to Erykah Badu and hip hop and soul music. I always have loved James Brown. Motown. The blues. Gospel music, too. I love listening to music that my friends make. Matt hosts musicians at his house (that was the first place I played in front of people) and I try to go a lot. I’ve heard so much great music and met so many wonderful musicians there.

When I play festivals I like to wander around and hear things. It reminds me of being a kid on the midway at the State Fair. I don’t even know the names of some of the stuff I like. I just like it.

I’ve been listening lately to a lot of Bob Dylan. Matt is a big fan of Bob Dylan, and if he’s driving, he’s got some Dylan music nearby. Recently he gave me the Trouble No More deluxe edition, and I’ve listened to it a thousand times. All 7 albums. I love how there are so many different versions of the same songs. I love his band and his backup singers. He seems to really be loving the music he’s making and that’s exactly how I feel when I make art or music.

Follow Daniel and Split Tooth Media on Twitter

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)