To preview the 2021 Flickers’ Rhode Island International Film Festival, Robert Delany discussed some of the most exciting films with their creators. Up today is experimental animator Catherine Slilaty

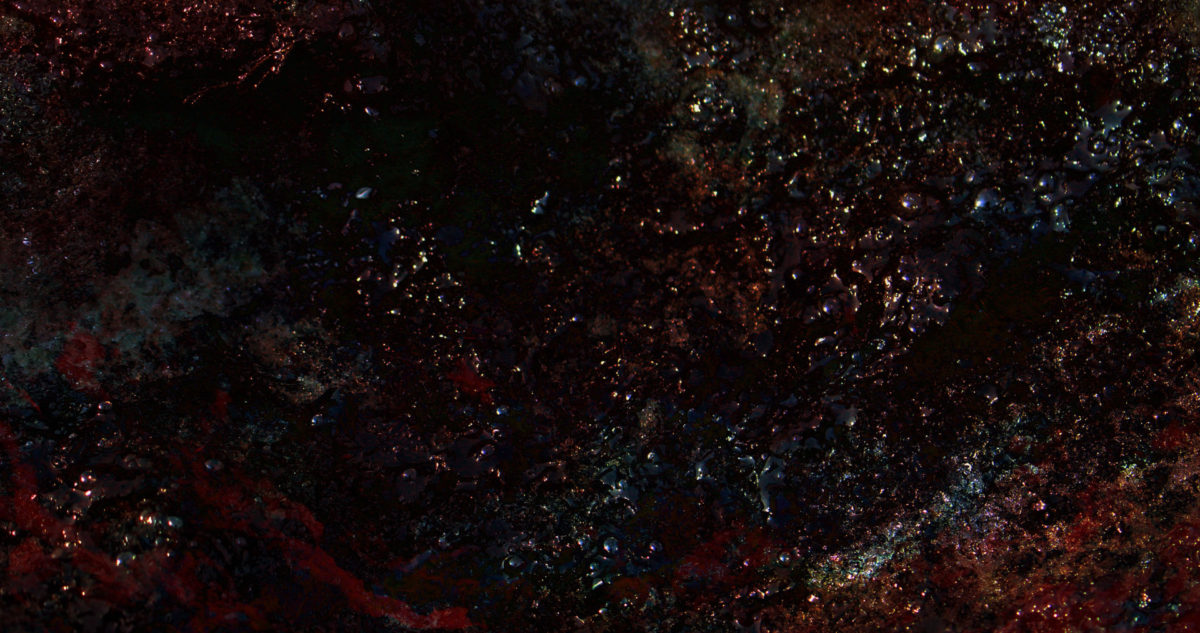

Over sounds taken from Yellowstone National Park, we see textures transform from light ripples of water to roiling mounds of clay; Darkness will resist light, envelope it, and vice versa as colors shift from opaque black, to blinding white, to blood red. In Moundform (Canada, 2020), directed by Catherine Slilaty, abstract organic forms boil on screen, where every aspect of the animation will change over the course of her latest short film. Slilaty aims to immerse the viewer in a cocoon-like atmosphere where the mind can rest and ruminate on the tumultuous world comprising different animation styles.

A painter and animator, Slilaty is currently pursuing an MFA at Concordia University. Moundform is an extension of her interest in exploring issues of identity and corporeality through moving images.

In an email interview, we spoke about her lifelong passion for art, the resilience of life, and the power of abstraction.

Split Tooth Media: In your research you are exploring the limits of the self, corporeality, and multiplicity through animation, painting, and drawing. How does Moundform factor into this work?

Catherine Slilaty: In this film, I was looking to create the feeling of being immersed in an entity that felt like an amalgamation of many creatures, many types of beings and existences: what that type of embodiment feels like. The abstracted approach allows for a focus on the visceral aspect of it, I found. And in terms of the techniques, it was very much with a focus on animation: hand-drawn animation and photo-animation specifically.

When did you become interested in animation and visual art?

I’ve been drawing ever since I was little. I loved drawing animals, dinosaurs especially, and this evolved into working with monsters, creatures and more abstracted forms. I’ve always felt like art making was going to be a part of my life. For animation, I gravitated towards it about seven years ago after thinking about what kind of skills I’d want to learn going to school for art. Animation involved learning multimedia techniques, editing software, technical art skills, and sound design: I was really interested in learning all these things and applying them together. I saw it as an evolution of my drawing practice.

What are some animated works or artists who have influenced your style of animation?

I love the works of Caleb Wood, Sonnyé Lim, Eric Ko, and Tatsuhiro Ariyoshi. They all have distinct styles and approaches, and what really stands out to me is how they make use of transformation animation and organic shapes. Their subjects are energized, lively, and there’s such a sense of delight for the movements themselves in their work, which is so infectious.

Related: RIIFF 2021 Q&A: Sandrine Stoïanov and Jean-Charles Finck’s ‘The World Within’ (2020)

Outside of animation you are also a multidisciplinary artist with a focus on transformation and in-between-ness in relation to identity. How have you explored this with other artforms, and how does approaching these ideas in animation compare with painting or drawing?

Animation is very much the ideal medium for the exploration of transformation. The level of control is very freeing and exciting: any creature can come to life, bodies can transform, warp, squish, and stretch limitlessly. Being a time-based medium, animation allows for a focus on the process of the transformation. Using time to draw out a transformation, no matter how big or small, can have as much of an impact as a more sudden, explosive movement. When working with animation, I’m usually thinking about how I can best create an immersive, impactful experience to explore my ideas so they can be felt in a way which evolves as the animation unfolds in time.

When it comes to drawing and painting, my approach is usually seeing it as a crystallization of a key moment of transformation: a moment of energy frozen in time. Something that is both what it was and what it will be. The in-between is a place of so much potential and history all at once. In both my animations and drawings, my subjects are always organic: inspired by flora and fauna, my creatures tend to be hybrids, abstracted blobs and strange monstrous bodies. Exploring identity/the self as something that is in becoming, ever-transforming and evolving is what I’m most passionate about as I feel it reflects the reality of being alive. Life is flux. Animation and drawing help me explore different aspects of that.

How did the idea for Moundform originally come about?

I wanted to explore the potential of darkness as a site for a sort of deep, gentle rest: a private, intimate space. The feeling that I always had in mind was that of being immersed in the murky depths of an enormous cocoon, a great womb of sorts. A place where the mind and body are in a state of rest so that transformation and becoming can be ends in and of themselves. This idea remained at the core of my approach throughout the process of making Moundform.

The form of the animation has an incredible liquid quality to it. The weight of the motion feels like it varies between light waves of water and heavy globs of clay. How did you develop the different textures to the motion, and what materials did you use to achieve these effects?

I used a mixture of 2D digital animation — various hand drawn loops of blobs — and photo-animation. The photos in question are of various substances, usually organic matter: blades of grass, snow, jam, concrete, etc. The images are looped into image sequences to create a feeling of movement through the textures and patterns in each image. I used After Effects to blend the images together at times: there’s also a fair bit of layering throughout the film to create this feeling of a murky, deep space.

This transformation also seems to extend to the modes of animation you are employing. Sometimes it seems like it’s painted 2D, and other times it looks like 3D stop motion. Why employ these different types of animation in the film?

Related: Stained Glass Daydreams: An Interview With Jodie Mack

When I discovered the photo-animation technique while learning animation, I fell in love with it and have really enjoyed mixing it with 2D digital hand drawn animation. This combination adds a lot of visual depth to the image, and a tactile interest as well. I also feel that including photo-animation of organic materials and other substances creates a sort of uncanny feeling: the viewer may recognize the texture, colors and shape as familiar, but the abstraction and processing of the image makes it feel strange, perhaps just out of reach of being fully recognized. It calls to our own memories and experiences of these images no matter how abstracted they are. I do feel that photo-animation is a way to document my surroundings, in a way paying homage to what always inspires me in the first place: nature. Integrating that in my work feels important.

There are stunning transitions between color design in Moundform: from dark blue and green tones, blinding white, opaque black, to blood red. What were you trying to achieve with these transitions in color?

Thank you very much. I see these moments as representing different transformative, transitional states within Moundform: feelings of emergence, glistening potentials, thrashing, panic, pulsations, exhaustion, and rest.

There is also an interesting interplay between light and darkness in the film. Light seems to be resisting the darkness and vice versa. Why construct this tension between light and dark in the film?

This calls back to the feeling of the murky cocoon that I spoke of earlier as being the starting point of the film. There’s an excitement and sense of power which comes from emerging from it, transforming, and exploring. But there’s also the fear of the unknown, the anguish of the unexpected, elation, and persistence. I think there’s a bit of all this in the light and dark.

The forms you manipulate in the film feel so organic, like the decomposition of leaves on the forest floor. What are the keys, in regards to technique, to making the form feel so biological?

I really focused on highlighting the natural textures, colors, and shapes of the substances I photographed while processing them to retain their tactility when animated. My editing was mostly focused on color balance and layering, as well as some effects that blended images together somewhat throughout the image sequences. But I kept this to a minimum so that the images would not feel too digital. It was important to me that Moundform feel like a cohesive organism despite all its different transformations.

The sound design contributes so much to the atmosphere of the film, with the integration of natural sounds from Yellowstone National Park. How did you develop the idea to use the sounds of Yellowstone specifically?

I love working with found sound, and I happened to discover this online library sometime ago. Listening to the recordings, I was instantly inspired. I knew I wanted to experiment with these sounds to create the feeling of a strange, complex creature in emergence. Many of the sounds I used are various animal sounds, including elk, bison, birds, and squirrels. Moundform actually began as the sound piece I created as a result of these explorations. It guided the visual production and provided a wonderful structure.

You say that Moundform is meant to “swallow the viewer into a body of unrest as it navigates saturation and disconnect.” Why immerse the viewer in this tumultuous atmosphere?

Moundform is very much a film about the resilience of life. Through dire moments, we adapt and change to be able to survive as human beings, and same goes for any living organism. The choice to build the soundtrack using animal calls was a way of speaking to their power, as well as the challenges they are facing due to the impact that human activity and climate change have on ecosystems across the globe. My aim was for Moundform to aid in reflecting on both one’s own personal potentials and triumphs over challenges, as well as reflecting on the condition of all living beings and ecosystems across the world. It’s a balance that is becoming increasingly delicate.

What makes abstraction in animation so powerful?

Abstraction in animation is very much a tool for immersion into the visceral, tactile, sensorial. There’s something freeing and stimulating that comes with abstraction and ambiguity. On some level I think we all have a tendency towards trying to ‘make sense of’ the abstract, but I feel it ultimately draws us in and allows us to focus on motion, rhythms and process instead. It’s a sensory treat, and there’s something undeniably playful about it which has drawn me to it.

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Robert on Twitter

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)