With a home video release of his first feature film, maɬni, now available, we spoke with Hopinka about portraying the Pacific Northwest on the screen and using cinema to preserve and revitalize Native American culture

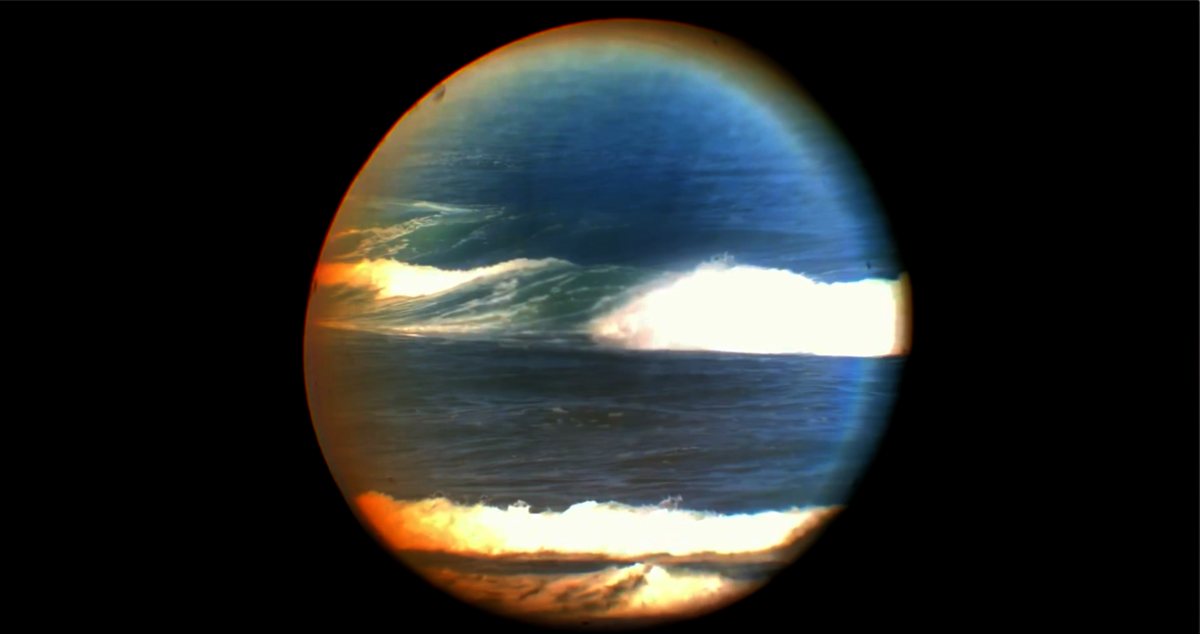

Sky Hopinka is a filmmaker whose work combines a deep exploration of Native American culture and history with complex experimental film craft. Hopinka’s work often utilizes mind-bending filmmaking styles. He layers various soundtracks and images on top of each other to create sonic and visual collages. He distorts, manipulates, and reconstructs images through color effects and unconventional editing techniques. Although Hopinka can mold these images drastically, his films also showcase the raw beauty of the natural world. Especially in his first feature-length film, maɬni – towards the ocean, towards the shore (2020), he constructs a vibrant and ever-changing portrait of the Pacific Northwest.

Many of his films demonstrate his passion for indigenous language revitalization, specifically regarding Chinuk Wawa, which began as a pidgin trade language before developing into a creole in the Pacific Northwest. His work focuses heavily on native communities and their relationship to the natural world, documenting everything from powerful performances of rituals relating to indigenous mythology and beliefs, to chronicling the Standing Rock Protests.

Split Tooth Media: With vast oceans, sparkling beaches, rocky cliffs, and dense forests, you portray the Pacific Northwest as a wide-ranging landscape in maɬni. Your work often highlights the natural beauty of the environment, but how did you want to communicate the particular aesthetics of the Pacific Northwest in maɬni?

Sky Hopinka: I remember really wanting to make a film on the Oregon Coast because it’s where I grew up. I love the gray skies and the rainy weather. I think it’s really beautiful. I had been wanting to make a film that captures that visually. maɬni really provided an opportunity to do that. Or it’s the excuse that I made to go do that, [in order] to revisit friends, to revisit these landscapes, and to try and capture the beauty of a gray Northwest spring.

In maɬni there is a central emphasis on water. We see Sweetwater Sahme do a waterfall cleanse, Jordan Mercier and others row traditional Chinookan canoes, and you also explore the Chinookan death myth where the ocean is tied to their vision of the afterlife. How did you aim to integrate the sacred connection between indigenous people and water into the overall composition of maɬni?

By presenting it in a way that is quotidian. I think presenting these things being inhabited, being used, being engaged with, not necessarily in a reverential way — though the reverence is there — but in a way that demonstrates that this is part of everyday life is really important for bridging those ideas.

The revitalization of indigenous language is central to your work, as is the decolonization of the names of places. You explore this in films like Visions of an Island (2016) and Kunįkága Remembers Red Banks, Kunįkága Remembers the Welcome Song (2014), where you highlight how the land itself was not only seized, but the language for the landscape was all but erased. What are the effects of revitalizing the names of places?

Place names are important because they are often descriptive. They often contain directions. They often contain information about what you can find there, what you can use there: food, resources, plants, etc. So understanding how we describe things or what we call things is an important part of recognizing the landscape as a place that is not just where you inhabit or visit, but also as a place you embody or that you engage with on more than superficial levels.

You utilize text on screen in a variety of ways. For instance, you have arranged sentences into images and situated the subtitles right in the center of the frame. When did you first realize that text itself could be such a versatile aspect of your filmmaking?

After seeing the work of Peter Rose and Basma Alsharif. Peter Rose’s work showed me the possibilities of language and different ways to think about language and words, especially on screen. Basma’s work about subtitles and about how the information is presented as a conversation of language and dialect — specifically in her film The Story of Milk and Honey (2011) — really opened my eyes to the tradition that subtitles and text on screen have in western cinema, and how to play with those expectations and those conventions.

How do you approach exploring the distant history of indigenous people versus chronicling contemporary events, like the Standing Rock Protests in Dislocation Blues (2017)?

I mean, the history is present every day. I don’t know if that sounds corny, but what we are living in today is an accumulation of those pasts, and those histories and those traumas and those joys and those things that have survived. And what’s also felt today in the present is a sense of mourning or loss of those things that didn’t make it or that you don’t have access to or that are gone. I am a big proponent of thinking about the present, or not necessarily thinking about the future or indigenous futurisms or futurisms in general. I think that’s important, but also, what are the things that are manifested everyday that are the intersection of the past and the future, which is, I guess, the present?

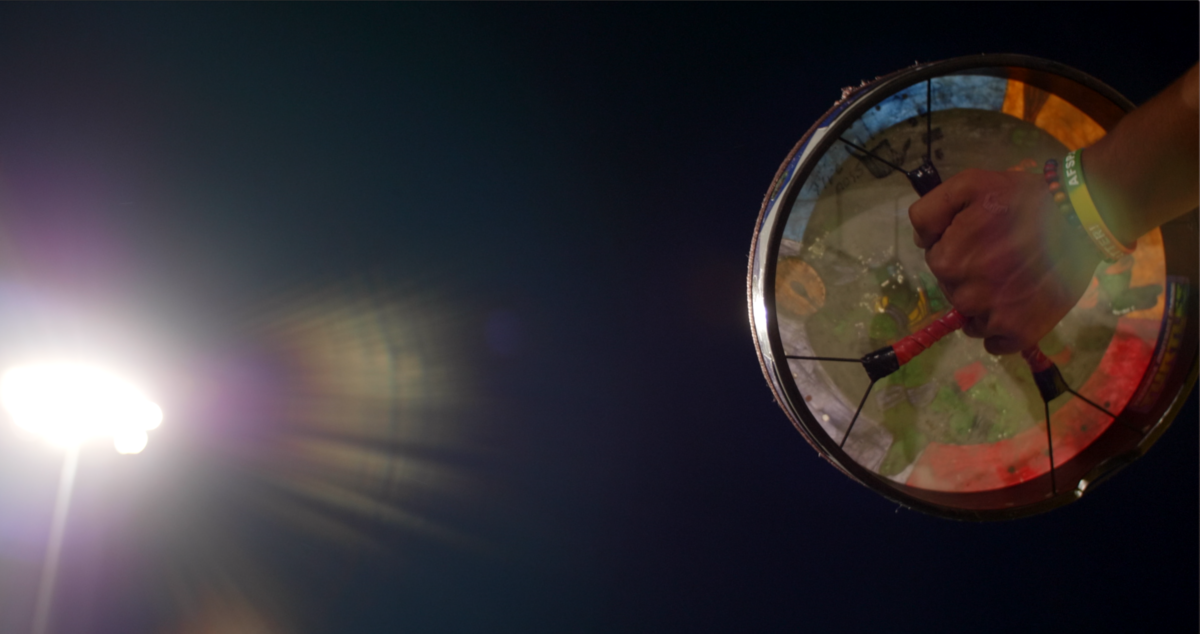

We see powerful performances of singing, drumming, dancing, and poetry in your films. What is it like experiencing, capturing, and presenting these intense performances?

I think they are fun to film. But also, I don’t film anything that isn’t meant to be filmed. There is a sense of sharing or to be observed in the Pow Wow or the drum group in maɬni. Just thinking about how people are presenting themselves, and how they want to be seen, and what am I getting permission to record and to film and to look at. It feels like there’s a play between the two. I think that film is a good medium for that, to let those who wish to be seen be seen. And also to give privacy and space to the things that aren’t supposed to be filmed or aren’t supposed to be seen.

I’m curious about a visual technique you use where you flip the landscape. The ground will still be on the bottom of the image, but it seems like the ground is also on the top of the image. It creates this natural frame or even a kind of iris. When did you first use that technique and what is its role in your work?

The first time I did it was with Jaaji Approx (2015). I had a picture in my head of what it would look like and found the two clips I wanted to use and learned how to rotoscope. It’s really intense and time consuming. In that film, I was really trying to think about these multiplicities, or multitudes of being, or of understanding a space, or a landscape, and, in that scene specifically, my relationship with my father. That’s me singing along to some recordings that he had. I liked to think about the visuals in that film as my way of communicating or responding to his songs. In sharing something that he felt like he was good at or that was a big part of his life and me doing the same thing with how filmmaking is a big part of my life.

And even with Visions of an Island, there’s a shot of a fur seal on the bottom of the frame. On the upper part of the frame is a 4th of July celebration on St. Paul, demonstrating cohabitation, the significance of these different sorts of relationships between this animal, which is a big part of the culture, and with the community, which is what gives the island life.

Visions of an Island is one of my favorite films of yours. I love the intro where you revolve 360 degrees and the landscape sort of separates and merges. Can you tell me more about how you created the intro in particular?

I like to demonstrate the tactics and approaches that I’m going to be using in a film early on. Just to lay my cards on the table, you know? I want to give you some tools to help navigate the film on its own terms.

For that intro I did two pans, and I was trying to figure out which one was smoother. So I just put them on top of each other and adjusted the opacity. But then I just really liked it. It’s kind of on the same pace, it kind of separates, and in one shot, my friend Robin is in the frame and in the other she’s not. It’s this strange sort of appearance of a person. I felt that shot was the beginning of the film because it offers an obscured subjective survey of this place, of this town, and of this island.

With that film in particular, the big question I had was how to not present myself as an authority or as a tourist that has some sort of expertise because I spent the summer on this island. I wanted it to be a bit vague. I wanted it to be a bit dreamy or like a vision.

Do you find that sense of illusion or obfuscation of the landscape extends to some of your other films as well?

Yeah, I’m always trying to find ways to film landscapes or to film places that are interesting to me. Not necessarily trying to be novel every time, but just trying to figure out what can a camera do in this place or what things are going on that I can respond to with the camera. That’s part of the joys of shooting: figuring out what I can do in a place with the camera, what can I do in camera, and then also what can I do in post.

For me that’s the joy of experimental film too, seeing how filmmakers can warp reality through their lens in that way.

Yeah, absolutely. You have a camera but every person is going to do something different with it. ‘Experimental’ cinema is a loaded word, it’s an empty word, but I like how empty it is. It adapts. What’s experimental to one person might not be to another. That gives a lot of room in a very small space for people to do different and exciting things.

In an interview where you speak about indigenous artifacts in museums, you said, ‘What happens to something that is very much a part of their culture that then gets taken away and put in museum glass? It loses its utility.’ How can filmmaking interact with or revitalize culture or history differently than other art forms or media?

It is both a tool for storytelling and preservation by its nature. I think that’s very fascinating, especially when making films that deal with myths or the reclamation of myths. But then I’m also actively making artifacts. So how then can they function as markers of the time that they were made, and as propositions themselves that hopefully other indigenous filmmakers can question, respond to, adapt or steal or whatever? I do like to think of the work that I make not as proprietary by any means. If someone sees something that I do in a film that they like, I hope they will make similar moves, respond to it, or build on it. I think that’s an important part of the potential for film: not necessarily viewing them as artifacts or objects, but as things to be riffed upon or to be utilized in whatever way that is inspiring.

Cinema has a long history of stereotyping indigenous peoples. As a filmmaker who presents indigenous culture from such a personal, respectful perspective, how can one counteract the more harmful examples from cinema’s past?

I think just having more space for more work by indigenous people that are either commenting on that history or just totally ignoring it. A thing I have tried to avoid is feeling like I have to respond to the canon or respond to those histories. I don’t want my films to just be responses to white perceptions about who we are or what we do. I’m a fan of work that cuts that part out of the equation, but I also love the work that comments on it in a really direct and aggressive way. The work of New Red Order is fantastic and necessary and needed, and so is the work of Fox Maxy and other indigenous filmmakers that are asking different questions. There are so many questions to be asked that could not necessarily be answered, but could be facilitated through film.

Another aspect of your filmmaking I find interesting are these shots where you are walking through the forest. It creates a sense that we are being transported into the landscape as you walk through. What role do these shots play in your work?

My hope with some of those shots is that they slow things down, set a pace, or replicate that idea of a stroll. Feeling unhurried is important with some of these works because they can be dense. The dynamics of pacing are pretty important to these works, not only for how I relate to them, but for how I want to give the audience breathing room to move through them as well.

Did you find making the transition from short films to feature filmmaking with maɬni to be a challenge?

It felt really natural to make maɬni the same way I make shorts, which is with me and a camera, seeing some friends, driving around, and editing. That felt comfortable as a foundation to try making films in a longer format.

When you say it’s just you and the camera, what’s that experience like having that autonomy over the filmmaking process, and do you think that’s a benefit of experimental cinema?

Yeah, definitely. A big part of why I leaned more into experimental film was because I realized I didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission to make this work, and I didn’t need to convince anyone to support the work or try to sell it to someone. On paper these films sound pretty… (laughs)… I don’t know what the word is, but it’s hard to get someone to buy-in with some experimental film loglines. If I just make it, then that’s the demonstration. It’s not me writing out a 500-word treatment, trying to get someone to support it. It made more sense just to make the work and then share it to say, ‘This is what I’m talking about. This is what I’m trying to do.’

When you are introducing people to this type of cinema, or this methodology or perspective on cinema, what do you find is a good way to describe it to a viewer who is new to experimental film?

Honestly, by starting with the word ‘experimental.’ Experimental means something different to an experimental film community than it does to someone that only has exposure to conventional documentaries or narratives. So starting off the bat with, ‘OK, this is going to be a little weird.’ Then also encouraging them that there’s no wrong way to watch the film. The things that you feel and the things that you experience are a valid way of experiencing the film. If you’re bored, if you get frustrated, that’s probably by design. Don’t stop at the reasons why you don’t like something. Ask yourself, ‘why do you feel that way?’ How then can that inform your viewing?

Purchase maɬni on DVD or Blu-ray from Amazon

Many of Hopinka’s films are available to watch on his Vimeo Page

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Robert on Twitter

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)