The most unnerving moment in Sledgehammer (1983) doesn’t even involve typical horror-movie horror of any kind. Just as the group of soon-to-be slasher victims arrive at the haunted country house they will be staying in, there is an extended — emphasis on extended — slow-motion shot of one of the couples walking across a field set to bright and cheery flute music. They embrace and laugh throughout their long journey across the short distance. At one point, the man tries and fails to balance a beer can on his girlfriend’s head. They seem to be without a care in the world (even though the previous scene found them arguing about the status of their relationship). This moment is so goofy, innocent, and sugary that its mere presence within a movie called Sledgehammer is enough to send bad vibes out to all your neighbors while you are watching. Like most of this movie, the scene shouldn’t work. But the languid pace and extreme duration is draining, as if we are watching the joy and youth being sucked out of these young lovers as the shot eventually fades to black. This long take has been compared to a cursed videotape, something like the infamous well footage in Ringu (1998), which is incredibly fitting for how this scene feels within the movie. But the fact that it has absolutely no supernatural over- or undertones while creating such an unsettling effect, is baffling.

Everybody knows a watched pot never boils and that staring at a tea kettle won’t make it heat up faster. It’s going to happen eventually. Giving too much attention to such a simple and mundane event only makes the seconds and minutes crawl. But when one actually does give their attention to the process of a kettle boiling, it has an oddly hypnotic effect. There is a strange tension as your senses are pinned somewhere between meditation and anticipation while you listen to the whistle gradually rise in pitch and wait for the first puff of steam to emerge. It’s almost disappointing when the water actually reaches its boiling point.

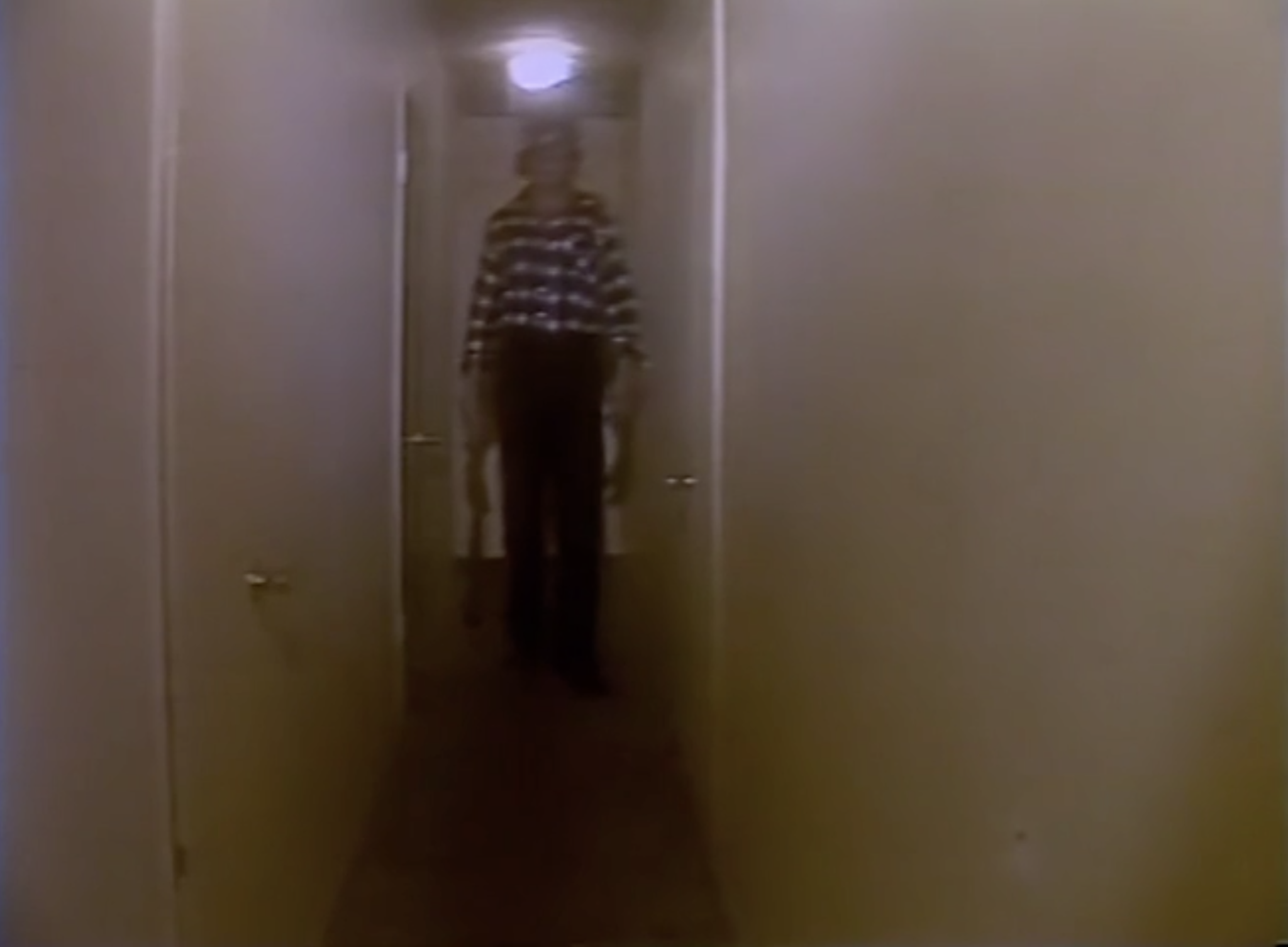

Sledgehammer is a movie that traps its viewers in kettle-watching moments. Perhaps best known as the first shot-on-videotape horror movie made for the home video market, the formal peculiarities of this movie outshine any importance that comes from such trivia regarding its release. Within Sledgehammer, the simplest actions are stretched out to extreme durations: long takes are repeated over and over in slow motion shots of looming figures stalking through glaring, fluorescent-lit hallways and down darkened staircases. The soundtrack, discounting the above-mentioned flute tune, is composed primarily of a rumbling, bassy drone that perfectly overwhelms the bizarre images passing across the screen.

Please don’t be mistaken — Sledgehammer is not a film that confronts us with profound meditations on time and temporality. We are not riding the rails of Stalker or doing chores with Jeanne Dielman here. The movie has your standard chases and kill scenes like any ’80s slasher and an incredibly disturbing villain dealing death blows with the titular sledgehammer. But this movie has something else to it that distinguishes it not only from other SOV horror movies, but within the horror genre in general. This watched pot boils.

It probably goes without saying, but the plot of this movie should matter very little to anyone watching it. Regardless, the “story” goes something like this: A mother runs away to the country with her lover. She takes her little boy along. In their isolated cabin, she violently throws the boy in an upstairs closet, locking him in so she and her man can have a romantic evening without disturbance. Something happens in that closet. The lock slides open on its own and a large, hulking figure emerges with a sledgehammer. The figure makes its way downstairs and brutally murders the two adults.

Years later, a group of rowdy hooligans roll up to the cabin and unload an army’s worth of party supplies. They hoot and holler about the wild weekend they are about to enjoy in the country. They have a food fight, they “dance” a bit, but they mostly act like farm animals and drown themselves in alcohol — seriously, the party scenes in this movie make the orgy at the end of Scorpio Rising look elegant. The macho leader of the pack (Ted Prior, brother of director David A. Prior) leads them through a seance to conjure the victims of the murder that took place in the cabin. The seance is a prank, but as it is taking place, the closet door opens and a flannel-clad giant in a plastic mask materializes in the house. He begins stalking and killing members of the group, shape-shifting between hulking flannel man and the little boy from the opening scene.

Taking place almost entirely within the cabin, Sledgehammer creates a totalizing and claustrophobic atmosphere with a logic entirely its own. With the flannel giant’s arrival, the cabin appears to transport its poor vacationing inhabitants into another dimension — full of endless hallways and unexpected teleportations between rooms. Escape doesn’t just seem impossible, it feels like the world beyond the cabin has ceased to exist. The filmmakers, tasked with having to make the director’s apartment look like a larger house, use repetitive and slightly altered shots of the hallways to stretch the space within the cabin to look bigger than the actual location. But the looping familiarity of the white-walled halls adds to the insular terror of the movie. Seeing the same shot of the masked killer walking down the same hallway towards the camera multiple times makes Sledgehammer function like a maze with only dead ends. Adding to the strangeness, no effort is made to explain any of the reasons why things are the way they are.

On a formal level, certain stylistic choices are as inexplicable as the narrative, most importantly, the use of slow motion. For instance, when the mother throws her son into the closet at the beginning of the film, the act of locking the door is stretched to an excruciating length. It is already a brutal scene as the little boy is treated so terribly by his mother. But the slow motion adds a sludgy weight to the action, with the lock being slid across the door in an extreme close-up, taking an eternity to click into place. In most horror movies, the slow motion would be used to accentuate the violence of a scene above everything. Instead, Sledgehammer draws out the simplest gesture to an extreme, creating a traumatic sensation through the elongation of time it takes for the lock to slide a matter of inches, sealing the poor child’s fate in the process. There are action scenes in Sledgehammer that use slow motion in more traditional ways, but it is the more unconventional applications of the effect that create the most lasting impression.

There is no reason why seemingly every other shot in Sledgehammer should be in slow motion. It also probably wasn’t necessary to conclude even the most inconsequential scenes in freeze frames or fadeouts either. The boring truth is that the director completed the movie and realized it was way too short to be called a feature, so he liberally applied these techniques to pad the time. But who cares about facts and trivia with a movie like Sledgehammer? The oddness of it is so all-consuming that the movie morphs your understanding of what’s what and what should be into some singularly strange netherworld of slug-paced, staticky madness. Sledgehammer reaches a point where anytime something even remotely “normal” takes place, it feels alien and out of place. Whether one appreciates the movie’s oddness or not, it deserves credit for its ability to put us in a position to feel unsettled by the most common and traditional of film techniques. That is an achievement that very few movies can lay claim to.

Find the complete October Horror 2021 series here:

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

Stream Sledgehammer here

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)