Alice Coltrane’s farewell to jazz, recorded live at UCLA, is her finest record — and her most demanding

The notes of the Wurlitzer organ spell out a solemn hymn, and Alice Coltrane turns to address the audience. She’s about to play a piece by her late husband John, and she’s explaining how the piece came to be. “He saw a vibration, and it was… energy,” she muses. We can practically hear her stare into space. Slowly, the notes of the hymn begin to sour, and the chords jostle against each other at right angles. “I want you to feel the full force of what this piece is about.”

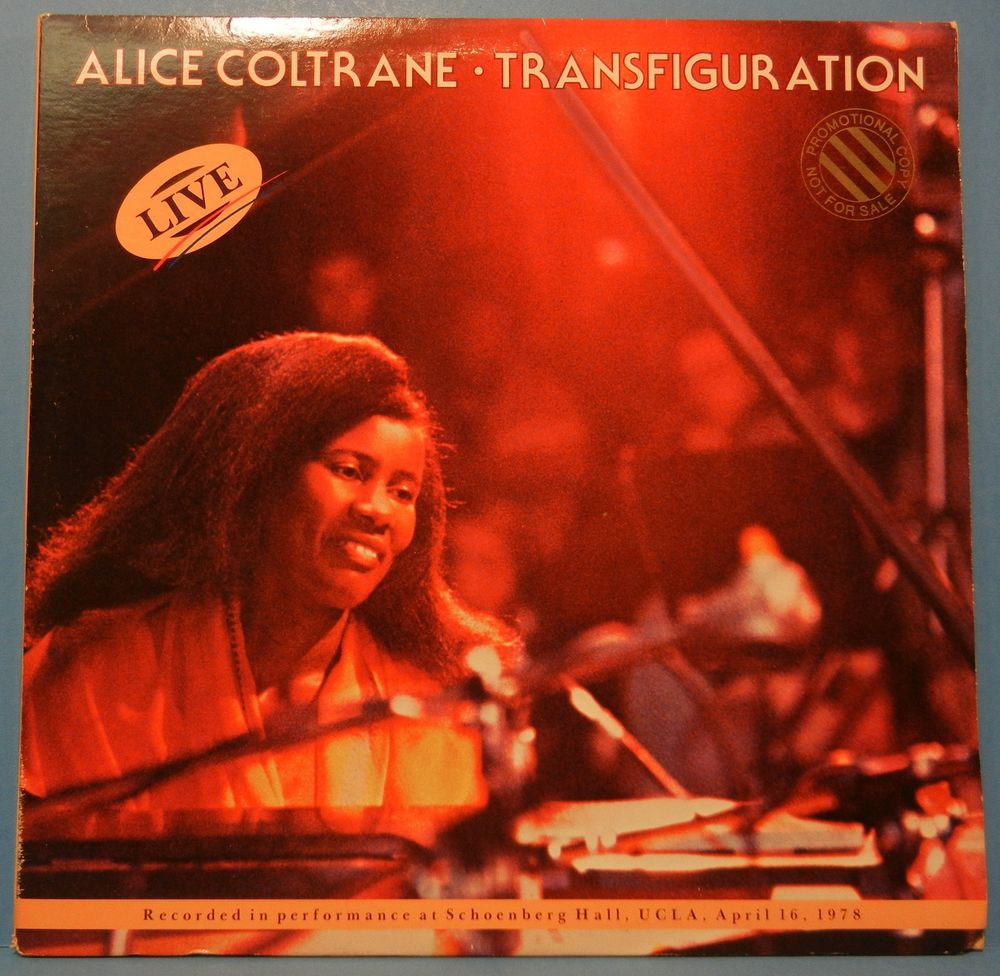

Without warning, the floor drops out from under us. Reggie Workman works himself into a frenzy, hammering the strings of his bass with such force it threatens to crack and splinter, and the high notes of Coltrane’s organ whoop and soar in an uncanny imitation of human speech. It’s absolutely relentless, and it doesn’t let up for more than half an hour. This is “Leo,” and it takes up half of Transfiguration, recorded live at UCLA’s Schoenberg Hall on April 16, 1978 and released later that year just before Coltrane retired as swamini of the Sai Anantam Ashram.

Coltrane would continue to make fantastic devotional music for her followers at her ashram, but this would be her final jazz record until 2004’s Translinear Light; it’s also, arguably, her finest.

There’s something about simple, meat-and-potatoes music — the kind made from the exertion of physical force on instruments—that feels more convincingly spiritual than that made by extensive layering and tinkering. The best music creates a world outside itself, something born from the music yet somehow beyond it, what’s meant when music is described as “evocative.” It’s more impressive when it’s made from a handful of instruments because the actual sound takes up less space than the extra-sonic aspect of the music, the spiritual aspect. That’s why Transfiguration haunts me more than any of her other albums: through the force of the sound being made, Coltrane and her band seem to be trying to will some cosmic change into being.

Much of Transfiguration, like the hymn and the solo piano mini-suite composed of “One for Our Father” and “Prema,” is hushed, music for prayer. These are the pieces with the most in common with her best-known work like Journey in Satchidananda and the ashram tapes, and by no coincidence, “Prema” is the only track on which Coltrane succumbed to the temptation to add overdubs: a low string section rumbles ominously over Coltrane’s piano. But the bulk of Transfiguration, including “Leo,” is ecstatic — music meant less for rumination and meditation than to actively channel something beyond itself. The sheer commitment required to play a piece like “Leo” suggests in itself a more noble intent for this music than simply making sounds.

There’s a neat parallel between Transfiguration and John Coltrane’s final recordings, which can be found on the poorly recorded but revelatory The Olatunji Concert. The two songs on that recording both featured Alice, and they’re each around half an hour long, give or take. Listening to those pieces, it’s frightening to imagine where John could have taken his music from such an extreme had he not died from liver cancer three months later. It also seems like a logical endpoint, jazz so extreme in sound and form as to push against the constraints of its physical medium. (Olatunji is only available on CD, and on most formats “Leo” is split into parts one and two, as it is on the vinyl.) It’s similarly hard to imagine where Alice could have gone from there.

Alice never made much attempt to wiggle out from under her husband’s legacy, so perhaps the parallel is intentional. Whether or not Alice intended to go out on a bang, it certainly works that way: music so far-out the only logical place left to go was the other direction, the path of order and quiet rather than chaos and dissonance. Or maybe somewhere amid the fire and fury of this music, she really had an epiphany so acute she decided to devote her life to the higher powers.

Related: ‘The Empty Foxhole’ By Ornette Coleman (1966) by Daniel Bromfield

There’s been a recent revival of interest in Coltrane’s music, spurred by a few recent reissues: Luaka Bop’s wonderful The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda, which compiles the best from her ashram tapes, and a reissue of Joe Henderson’s The Elements, on which Coltrane was a key collaborator. A few nods from Pitchfork have been helpful as well: the inclusion of Turiya Sings on their list of the best ambient albums, plus a retrospective piece in 2017 for their magazine The Pitch. Unsurprisingly, this revival has mostly focused on her earlier, easier, more ethereal records; a later, weirder, less instantly gratifying work like Transfiguration is easily lost in the shuffle — it doesn’t help that she has an album called Transcendence as well.

As you might have surmised, this is not easy music. And whether Transfiguration is something you’d even considering playing depends on your tolerance for dissonant pieces that speed past the 10-minute mark and sometimes much further. Music like this is best enjoyed by those willing to engage with music on a spiritual level. Maybe you don’t believe in a cosmic force governing the universe. Maybe “vibrations” and “energy” sound like hippie bullshit to you. But if you’re willing to imagine for a second that there’s something out there that can make itself known through music, Transfiguration might be the closest to God you’ll ever get.

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)