An overlooked masterpiece of modern independent filmmaking, the debut feature from Jennifer Shainin and Randy Walker deserves rediscovery

Whether it is caught up in the dullest or most perplexing experiences of its characters’ lives, Apart from That (2006), the first and only feature film from Jennifer Shainin and Randy Walker, finds a vitality in every moment. Something is always in the making as the film burrows into its small community in central Washington. Apart from That arrived at the tail end of an era in American filmmaking where every movie was attempting profundity by tying large ensemble casts together in grandiose fashion. But Shainin and Walker locate subtle, yet striking, connections between their diverse set of characters and celebrate the bizarre nature of the little things they do on any given day.

Apart From That begins by throwing us into the middle of a house party. We are introduced to most of the principal characters, but the bustle of the scene grants only snippets of their personalities. Only upon reflection does it become apparent how rich these tiny, fractured glimpses are. Peggy (Alice Ellingson), an elderly woman who isn’t shy in pursuing her desires for attention or connection, gets stuck inside her shirt while trying to take it off in a back bedroom; Sam (Toan Le), a banker, is cornered by a man who tells him that his adopted son, Kyle (Kyle Conyers) has been swearing and talking about sex in front of his own boy. Ulla (Kathleen McNearney), a quiet and lonely hairdresser-in-training, struggles to get a word out when asked about her life. Leo (Tony Cladoosby), a roadworker, wanders through the gathering taking in all the odd little occurrences.

After the party, Shainin and Walker dial their scope down to a smaller ensemble of characters. The rest of the film follows them through a few days leading up to Halloween. Ulla rents a room from Peggy, and the pair act as the film’s core odd couple. Peggy gets her kicks calling in false alarm fires and greeting the firemen in the buff. She dances for the young street racers who live across the street and asks the DMV instructor who chauffeurs her home if he thinks she’s attractive. Ulla, by contrast, is incredibly reserved. When she isn’t at beauty school, she privately documents the sonic landscape of Peggy’s house. She records Peggy’s breathing when she sleeps, her voicemail greeting, and the sound of her fridge. Leo is called upon by everyone to help out with their troubles, but struggles to face his own when he is told a dear, sick friend is close to the end. He is apparently on the outs with his wife and spends nights in a motel. Sam is forced to fire a friend, Lee (Gary Schoonveld), at the bank. Lee also happens to be the father of his son’s best friend. The firing creates tension at home as Sam struggles not only with explaining the event to Kyle, but in separating personal guilt from his professional obligations.

While Apart from That could easily be lumped in with all those “everyone’s connected” ensemble epics like Magnolia (1999) that arrived at the turn of the millennium, Shainin and Walker are doing anything but following a trend. For one thing, the links they forge between their cast are not huge and life-affirming. Absent are the heaven-sent frogs falling from the sky; in their place are delicate parallel points being drawn between people who are stuck in their bodies and trying to navigate their lives with whatever grace they can muster. As with seemingly every movie about non-super human characters, some reviews for Apart from That accuse the film of merely slicing life or forcing mundanity upon viewers. Walker’s website places a particularly extreme quotation from an online review front and center, which calls Apart from That “The film you use to punish naughty children with.” But the connections and contrasts he and Shainin build between the cast are of the kind evoked only by artists who refuse to see “everyday life” as bland, or imperfect characters as pathetic. Shainin and Walker don’t reach for the divine but instead seek out the color and the life in small details and unremarkable places.

The film’s sequencing is one of its greatest strengths. The links that guide viewers across scenes are often instigated through the visuals, with match cuts of a pose being struck or a pattern being established as a motif that carries over. But the most crucial parallels established between characters come through emotional and situational means. For instance, a scene of Ulla being invited to an intervention for a classmate is intercut with Sam firing his friend at work. The two scenes are staged privately in public settings — Ulla is pulled aside outside of class, while Sam’s friend, unaware of what’s about to happen, insists on keeping the office door open to let fresh air in. Through the intercutting, Shainin and Walker open up nuances in each scene that might not have been brought out had they been played separately. In one, the familiarity between the men makes the firing seem oddly personal as it arises amid jokes and banter. In the other, Ulla, a bit of a loner, seems almost excited over the idea that her classmate would think to invite her to an event outside of school. They make plans and part as if they scheduled a night out. Placed together, the similarities between the two meetings draws us to the weight of personal histories and private desires as they are heaped upon each interaction — one ending in strange but mostly hopeful connection, the other a pained termination not only of a job, but potentially of a friendship.

Shainin and Walker add odd little touches to disrupt the dramatics or events within each scene, for their characters and viewers alike. Our attention is often split and interrupted through thoughtfully placed diversions. For instance, Ulla’s intervention invitation is staged in an alley parking lot. As she and her classmate discuss the intervention, a bag, left teetering on a truck, thuds to the ground and startles the two women. Their fellow beauty schoolers pass through periodically in the background, all carrying their practice dummy heads. Kyle returns from school and prepares a bowl of cereal in a scene that wouldn’t be out of place in Gummo (1997). He watches a strange PSA on gun violence and pretends to shoot the subject on the screen. While all of this is happening, a box turtle balances on a mug in the middle of the table. When Peggy calls the fire department in order for her favorite firefighter to “catch” her in the nude, the scene hinges on how the firefighter who arrives on scene, not the one she was hoping for, can’t help but crack a smile at what is essentially a crank call. He is clearly a bit annoyed — this isn’t the first time Peggy has called — and does his job in telling her not to repeat her offense again, but the humanity of the encounter is far from lost on him. Scenes such as this make it all the more surprising that negative reviews describe the film as being so dour, or characters like Peggy as “irritating” or unredeemable.1 The Seattle Times went so inexplicably far as to call it “exasperating,” while conceding that it is “brimming with life in all its awkward glory” and filled with “little miracles from start to finish.” It’s as if the reviewers are responding merely to the events of the film — such as a lonely woman, desperate for attention, calling in a fake fire — rather than the situations, which layer so many different perspectives and tones upon simple frameworks.

Apart from That is built around several other intervention-type events, though some don’t take place at all or are avoided by the characters in favor of more shielded interactions. Some take place as reenactments or practice runs staged by the characters in efforts to understand how an event could proceed or how one actually took place. Shainin and Walker made the brilliant choice of setting the film during Halloween to add a further theatricality to the proceedings. The costumes, masks, and seasonal decorations create a more abstracted plane for the characters to interact on. One example finds Ulla calling over Peggy’s family, caught in full costume while en route to a Halloween party, to meet with Peggy and discuss some serious issues regarding their estranged matriarch. When Peggy challenges them to open up emotionally to her, they struggle to meet her at the level of honesty that she tries to instigate. They let past grievances get in the way; they cover up and hide under their costumes. They won’t even give her a good hug! But the painful scene leads Ulla to recognize something she hadn’t noticed in her roommate before. When Kyle, out with his father on a day trip, tries once and for all to understand how his father could fire his best friend’s dad, he asks Sam to reenact the firing. Sam becomes visibly uncomfortable, as the familiarity shared between himself and Lee makes any truthful retelling of how the firing happened — with all the inside jokes and odd tangents that naturally pop up between longtime friends — seem ridiculous. Kyle listens but struggles to piece it all together, particularly how there could have been laughter during such an event. He spends the reenactment asking questions from behind a tiger mask.

Related: Explore our essay and interview series devoted to the films of Frank V. Ross

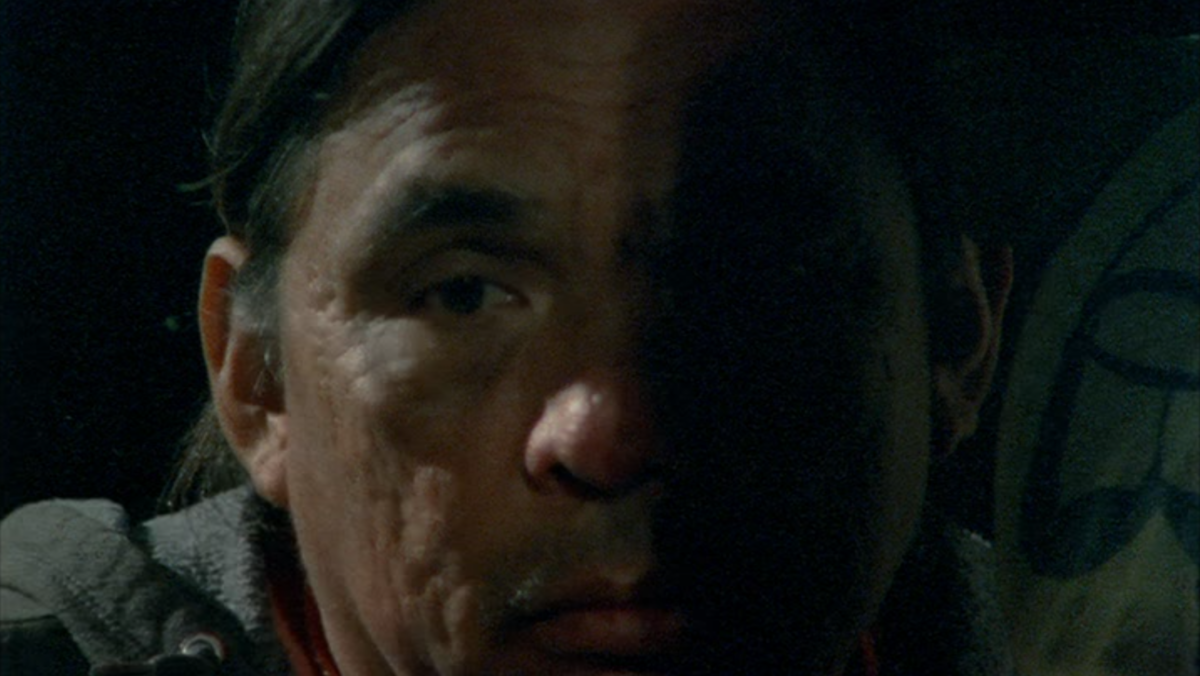

Leo wanders most easily between the various environments and social groups within the film. But his ability to slip into situations and navigate different types of relationships often appears to be a way of avoiding more direct engagement. He’s the most willing to interact with anyone who crosses his path. But he often instigates these interactions in ways that steer into childish diversions. His relationship with his family seems to be rocky. He arrives dressed for Halloween, ready to play with the children, but a tension in the house is palpable. There is a distance to Leo, yet not necessarily an alienation. Everyone around Leo chides him to go visit his dying friend before it’s too late, but he procrastinates. He pursues every distraction that comes his way. Instead of a direct interaction, he eventually visits the sick man through his window at night as he sleeps to share a private moment with him. The interaction is staged as a stolen, silent prayer. The scene is offered so delicately, yet it hits in a way that anchors the entire film. It’s an avoidance of facing a hard emotional moment in a certain sense, but it’s also such a naked display of affection. It allows for a final interaction grounded in love and stripped of the conventions and graveness of a last visit. Leo is able to say goodbye and commune with his friend in a way that doesn’t require any social masking.

Towards the end of the film, Peggy suggests that there is a freedom that comes with being a stranger (“Anywhere else in the world, you can meet strangers, be a stranger…”), an idea that Apart from That explores throughout. The ties that connect us can certainly bring love and support, but they can also suffocate. A different, liberating type of love develops among many of the characters when they take a step back to meet each other at a distance — to recognize each other’s desires and flaws freed from familiarity. Apart from That sustains that loving distance in a manner that invites the most subtle complexities to come to the fore and allows for old love to be cast under new light.

Apart from That is available to watch on Randy Walker’s ForeignAmerican Pictures website along with several short films. (Author’s Note: I recommend, especially for any readers from the Pacific Northwest, Return of the R, a short documentary about the iconic Rainer Beer neon “R” sign returning to Seattle.)

For anyone looking to own the film on DVD, send an email to [email protected]

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)

- In an interview for Transmutative Cinema, Shainin and Walker mention that during Apart from That’s festival run, they received questions from audience members such as, “Why are your characters so depressing?” and “Do you hate your characters?” The interview is available on YouTube.