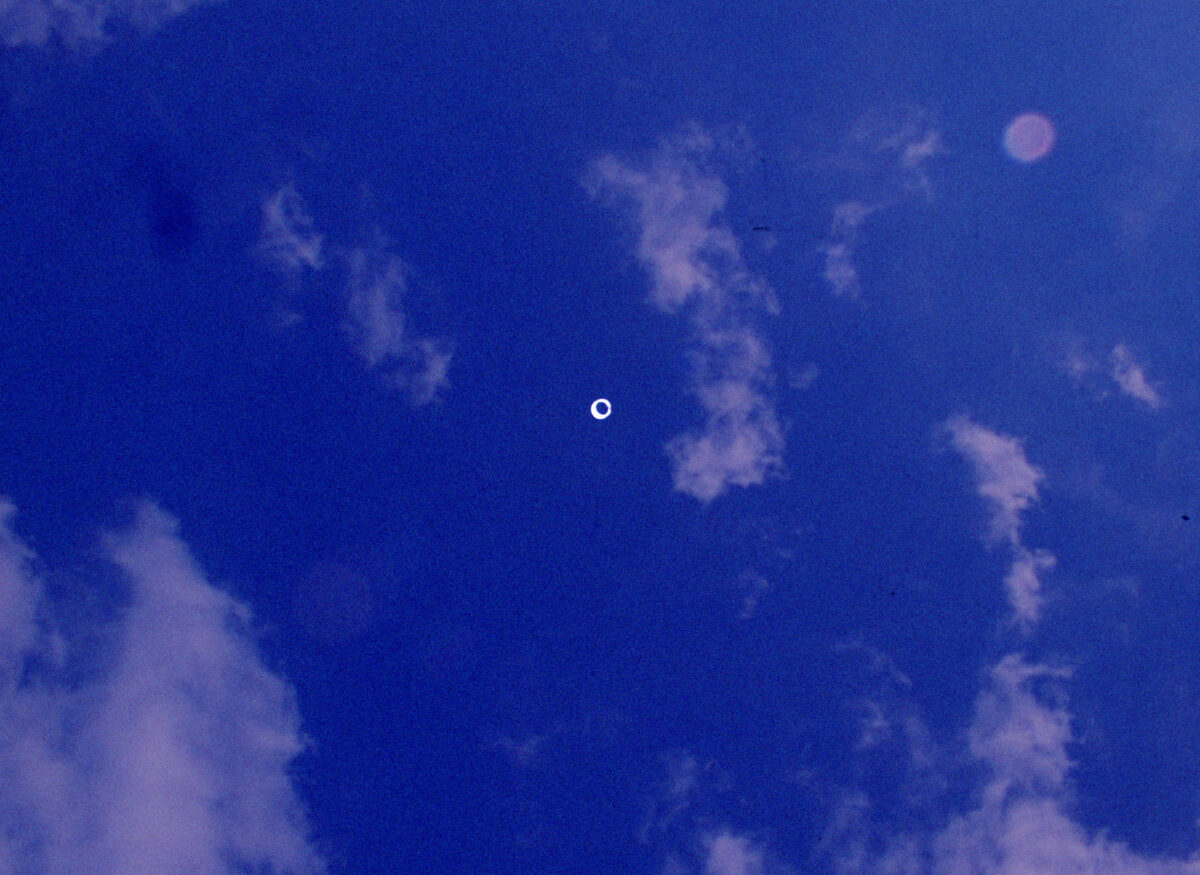

With its first wave of releases available now, Black Zero is shining a necessary light on classics of Canadian experimental cinema. The new home video label, founded by Stephen Broomer, offers not only beautiful restorations of rare and forgotten films, but also artfully crafted experiences that feel like personally guided tours into the minds of the artists who made these secret landmarks of North American filmmaking. Black Zero’s first three releases — John Hofsess’ Palace of Pleasure (1967), Keith Lock’s Everything Everywhere Again Alive (1975), and Arthur Lipsett’s Strange Codes (1975) — stand as a bold and diverse offering of different styles of non-narrative cinema. The films range from psychedelic kaleidoscopes of sexual desire, to an elliptical diary of 1970s communal living, to a tragically misunderstood “Trojan horse” comedy by a former boy wonder of found footage collage work.

Sure, every label out there is curating, picking films to champion, and, to varying extents, shifting the way people understand and experience each film by stamping its brand on them. But Black Zero offers something more personal. Broomer not only burns, assembles, and ships off each physical copy of the films himself in true DIY style, but he puts all of his various talents as a scholar, filmmaker, and video essayist to use. Each film is a work that Broomer not only finds historically important, but that has personally provoked and inspired him. Broomer’s commentaries and essay work included on these discs are both loving tributes and stylistic autopsies done in effort to understand the artists on a deeper level. These releases offer some of the most passionate film advocacy and scholarship I’ve encountered in years. Through these home video releases, Broomer is asking questions about how each film works from the inside out. Each disc feels authoritative but also encourages viewers to go further into the mysteries presented by the films.

The following interview was conducted with Broomer throughout June 2023. We spoke about the history and future of Black Zero, the personal ties Broomer has to the films and the artists behind them, and his dedication to preserving and promoting the legacy of Canadian underground cinema. Along with Black Zero, we also talked about Broomer’s upcoming book on Arthur Lipsett, and his website, Art & Trash, which is gearing up for a new season of video essays.

Split Tooth Media: You are a true multi-hyphenate: filmmaker-scholar-preservationist-author-video essayist… the list goes on. With Black Zero, you are merging all of your passions together to release experimental films that may have been left obscured by time, had you not stepped into the realm of home video. What were your first experiences with experimental cinema and when did you start making your own films?

I had a degree of exposure to weird art because my parents were interested in art. They had very broad, modern and postmodern ideas about art. Through my father, I had exposure to avant-garde music. My mother would take me to movies. At some point, with all my different interests that were developing in the beautiful isolation of my parents’ basement, which was just chock-a-block with books, I found myself reading old underground film books, in particular Sheldon Renan’s An Introduction To The American Underground Film (1967). It’s an encyclopedia of underground film with vividly drawn descriptions of artists and their work, including many artists who have fallen far away from us but who were at the heart of the zeitgeist in that time. This book came to me at the same time that my brother and I were both becoming really interested in film. I became interested in filmmaking through my older brother’s example.

We would watch a late night movie show that was beamed into our home from nearby Buffalo, Offbeat Cinema, where the hosts would play these Maynard G. Krebsian beatniks. They would sit around saying things like, “Wow, that movie was fly, daddy-o,” while wearing berets and drinking coffee. The kinds of movies they would play would paint an alternate world of late night coffee houses where people had what sounded like hip conversations about intelligent things, and even if the conversation wasn’t intelligent, the subject was. The films they presented were very diverse. The show introduced me to this world of movies that were an alternative to what I would see on another show, TV Ontario’s Saturday Night at the Movies hosted by Elwy Yost, which was very ‘high culture’ by comparison. We’d see Hitchcock movies, John Ford movies, and then, after midnight, we’d turn on channel 14 and we’d see Glen or Glenda, The Giant Gila Monster, and Carnival of Souls. So we developed this really broad sense of cinephilia by having these experiences. Somewhere along the line, I also started to see releases by Mystic Fire Video of films by Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren, and Shirley Clarke. I have really vivid memories from my early teenage years of seeing Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, The Connection, and At Land.

I was really eager to dive into that side of cinema. But I don’t consider it as a schism. I was interested in experimental films, but I was also interested in mainstream films and trash. I didn’t think one was better than the other. I just understood them all, naturally, to be different — they offered different pleasures and different experiences. I got to university, and found that there was a real hostility towards experimental film in the department I was in. It was all I wanted to do but I realized I wasn’t going to be able to do it there, so that’s how I developed more conventional skills in making documentary and fiction films.

Could you give us an idea of how Black Zero started? Was there a specific point when you realized you had to be the person to release these films?

I had drifted away from making experimental films early in my university degree. By the time I finished my degree, I was pretty bored with making documentaries. When I started my master’s program, in that same department, I knew that there were a number of Canadian underground films that were in need of preservation and restoration and no one was doing anything about it. Through the course of my master’s thesis, I restored twenty-odd other student films of the 1960s and ’70s, including Palace of Pleasure, all made at a regional film cooperative, the McMaster Film Board, which was based at McMaster University in Hamilton. At the time, there was no possibility to release my restorations on home video. There was no market and the technology was inaccessible. Instead, I was touring the films around art galleries, cinematheques, and museums. I would get paid an honorarium, and that would help to fund the work. While I was doing my PhD on Canadian avant-garde film, I was also pursuing little restoration projects on the side, doing the kind of work I knew distribution centers, art galleries, and institutions were not equipped to do, for whatever reason.

Around 2015, a friend and I came up with the idea that we could start a home video company. We could do it in an affordable way and it would serve as a culmination of my work in this area. At the time it was starting to seem like I wouldn’t be able to continue to restore films and tour them, because of diminishing returns. The well was running empty. It didn’t seem like it could turn into a proper career. So I had all these projects but I wanted to extend their life. We started work on Black Zero, and unfortunately we announced it prematurely. There was a lot of interest in it, but we were struggling to get it underway. I remained devoted to the idea that we could make it happen. But it was met with a lot of delays. When I finally pulled together the means to do it, the pandemic happened. That threw everything into flux. It took another couple of years to get everything in place.

Palace of Pleasure was believed to have been lost. How did you track it down and go about restoring it?

Palace of Pleasure was in fragments. Prints of it had been deposited in Canada’s national archives with errors in their identifying records. The fact that it was a dual-screen work was unknown to the people who donated the film to the archive, who had also been misidentified at the time as copyright holders. At that point, I had access to individual fragments in the possession of the filmmaker, John Hofsess. And so the work ended up becoming a matter of getting the archives to do the digitization work, which was often a very complex and restorative process in itself. Then I would take their scans and integrate the material that I had, with Hofsess giving input to the accuracy of what I was doing. This was done in 2008. In 2015, the year John died, I was able to create a new, higher resolution digital restoration.

It’s unfortunate that we don’t have the negatives. John was adamant that the negatives were destroyed, that he had thrown them away, but I still hope that they might turn up. I’m always hopeful that we can improve upon any digital restoration.

There is a definite sense that all of these Black Zero releases are of films that are very personal to you, but particularly Palace of Pleasure. It should be noted that the Black Zero name comes from this film. You have mentioned in emails and past interviews that you were quite close with its director, John Hofsess. When did you first learn about his work and how did his film become Spine No. 1?

I first became aware of John when I was watching a documentary about the Sue Rodriguez case in Vancouver, which was this watershed case in Canadian law around the right to die. Hofsess was the head of the Right to Die Society of Canada and Rodriguez was a woman who was living with ALS and who was petitioning the government for the right to an assisted death. It’s a cinema vérité documentary, behind the scenes of the media blitz surrounding Rodriguez. Hofsess comes off as kind of ghoulish… I’m not speaking ill of my friend here, but there’s no question what his flaws were: his need to exploit situations and people, often to noble ends, but noble ends that became cloudy and murky because of his methods. His methods with Sue Rodriguez are nothing that I wince about or am shy about. He wrote her most beautiful speeches. She gave a speech called “Who Owns My Life” and every word was written by him. In his way, he loved her and he supported her. By the end of the documentary, he has been ostracized from her campaign, because he signed her name to a letter she didn’t write, which was interpreted at the time as taking away the agency of a woman whose agency was already under duress, a really gross and painful violation; but one could also say, of course, that he was just doing the same thing he had always done in their relationship, writing a public speech for her…

So that was my first experience of seeing John, but I knew the name because there was a book written in the 1970s called Inner Views: Ten Canadian Film-Makers, a collection of profiles written by John when he was the film critic for MacLean’s, a Canadian cultural magazine. So I’m watching this documentary and, in my mind, I’m making the connection that he used to be a critic. Then my father turns around to me and says, ‘Oh yeah, that’s John Hofsess, he used to be an underground filmmaker.’ My father hadn’t known him, but they were in the same circles in the ’60s.1

I began to look into John a little more and realized he was connected to all of these stories I had heard in high school about Ivan Reitman, the Canadian filmmaker, who had made a film called Cannibal Girls. The stories I had heard were that Cannibal Girls had been banned. But that wasn’t true. Reitman had, a few years earlier, produced a film by John Hofsess called Columbus of Sex and that film had been banned, and Ivan was convicted for his role in producing it. Cannibal Girls is actually just Reitman doing what he does best, commercial exploitation, whereas Columbus of Sex is an art film that was persecuted for being too frank about sexuality.

I found out about Palace of Pleasure and I was fascinated by its mission: the idea that film could be a kind of psychologically emancipatory force. Later, I would see that these were ideas that had passed all through the history of modern experimental film, but at that time, I had never encountered filmmaking with an implicit, psychoanalytical purpose before. I assumed Palace of Pleasure was a lost film then. Through the course of my master’s thesis, I found out it was still in existence, but in pieces.

How did you meet John Hofsess?

Finding John was difficult. A couple of things had happened. He had potentially been implicated in what was considered on the books to be a murder, but which was really an assisted suicide. But that’s the trouble with the laws in Canada. And around the same time, some friends of his in the right to die movement who were living out in the prairies had been killed. This is the story as I had heard it, and for these reasons, he had gone into a kind of exile or hiding, living in a retirement community in San Diego. Through his former colleagues who had taken over the Right to Die Society from him, I eventually was able to make contact with him. He had really cut himself off from the various lives he had led before. He had been a pioneering figure in a lot of human rights challenges in Canada. He had gotten fixated on the cause for the Right to Die because of a couple of experiences he had had in the 1980s. One was the agonizing experience of witnessing his mother’s slow demise. The other was when his friend, Claude Jutra, killed himself when his own faculties began to fail him.

John had that heavy cloud over him and it took a while for us to develop a sense of trust. But in hindsight, he trusted me very quickly and with an awful lot of intimate stuff. He had a degree of personal ruthlessness that I’ve always admired. We became uneasy friends at first. I would say we were maybe always uneasy friends, partly because I knew more about his life than anyone else who knew him, because I had studied him before I met him. All these people who knew John knew only little pockets of his life. They knew him from the contexts they met him in, and his contexts changed every few years for 40 years. But I knew about all of it. I think he was glad to have someone who knew him to that degree because he didn’t have family. And I guess, in some strange way, I was like family to him. We were friends for a long time, about nine years, from when we met to when he died. It was a strange and strained friendship. We would sometimes go six months without speaking. We had probably only a dozen phone conversations, but we had a great deal of email correspondence. By the end of his life, he was putting me in a slightly difficult situation and would ask, ‘Hey, could you lend me some money?’ It was very sad and very hard, and I couldn’t say no even though I was struggling, too. I would always do whatever I could to help him out.

The last thing he asked of me was particularly difficult. He asked me if I could accompany him to Switzerland so he could have an assisted suicide. And I said, ‘no.’ I don’t really have any regrets about that. If I had gone, I would’ve been known as the guy who ‘went and killed John Hofsess.’ It’s painful though, because we were close and I didn’t want him to be alone, or with strangers, vultures, and I think that’s how it ended up. One of the things that arose out of our friendship was a greater and deeper conviction on my part towards the ideas that he had espoused in the 1960s. Knowing him as I did, I could see a clear thread from one emancipatory sensibility to the other, where a lot of other people, including people who admired him in the 1960s, were justifiably apprehensive of the transition of his ideas from sex to death. The fact that he had gone from fighting for emancipation through pleasure to emancipation through the end of consciousness… I’m apprehensive of that myself. I think that John’s motives are strange. But I also think that they are tragic and beautiful.

And that formed part of what I carried over into my own art, alongside lessons I had learned from my friend R. Bruce Elder, who was my doctoral dissertation supervisor and who had been a classmate of John’s in the ’60s. His own films also, from other sources and impulses, follow that same thread of the emancipation of the soul. I think that’s something that actually coheres around a lot of the kind of art that I value: a path to freedom.

Palace of Pleasure was intended to be a trilogy. The Black Zero disc includes a film you made called Resurrection of the Body, which is a “speculative” sequel, or finishing piece, to Palace of Pleasure. With all of your experience with Hofsess and his films, how did you approach this project?

I knew I needed to put John to rest and I had already tried several times to find a way to do that.2 It never felt like enough. Probably because I loved him, he was my friend, and a kindred spirit who had made a major impact on my life. Around the time John died, within a few weeks, my book, Hamilton Babylon — on Palace of Pleasure, The Columbus of Sex, the McMaster Film Board, and John’s philosophy of art — came out, but that’s not a total statement about his life because that only deals with the five years of his public life, and more than that, it’s a social history, about many lives and ambitions coming together.

John had always wanted me to help him make the final section of Palace of Pleasure, which he called Resurrection of the Body. For him, the title came from Norman O. Brown’s Life Against Death, a significant post-Freudian psychoanalytical tome from the ’60s. The title obviously has religious allusions, but in Brown’s pantheistic worldview, it is at least partly the limbs of Osiris being planted all across the face of the earth; it’s the translation of the soul through the destruction and reconstitution of the body. The meaning of this title started to take on a greater dimension to me than it ever could have for John, because of the context of his life and death.

I think John was embarrassed that Palace of Pleasure was incomplete. When he died, I felt it wasn’t fair to leave it unfinished. But it had to be something different than what he wanted, which was a film that bore only his political ethos enacted through dramatic staging. The way that he conceived it, it was an imitation of Palace of Pleasure. It wasn’t altogether, in my view, sincere. Maybe that’s a harsh thing to charge somebody with, I don’t mean it to be. He was doing his best. But I started thinking, here is an opportunity to make Palace of Pleasure about him. He had always posed his project as if he was a doctor prescribing sensual emancipation to somebody else, but it was never about other people, it was always about him. So it seemed to me that the appropriate way to end this story was by building it out of footage of John and making it allusively, and elusively, about his politics, his challenges to the government, his challenges to us as a society, and to make a film about a man whose relationship with death is mythic and total and complicated. There’s no decisive statement made by the end of this film, but I’ll say my approach is informed in part by my knowledge that John believed firmly in assisted death as a means of ending suffering for the terminally ill, and for him, his emotional situation was terminal and untenable, health regardless. His suffering was obvious and lifelong, and I wanted to do something that acknowledged that. I think part of his problem in life and why he always sought acknowledgement and endlessly pissed people off by seeking acknowledgement, was that he never received acknowledgement. So I wanted to make a film in which he becomes an icon. On some very literal level, it is my film, but it’s also our film. It’s a posthumous collaboration in the fullest sense.

Your speculative reconstruction of The Columbus of Sex is also included on the disc. What information and resources were available to guide you in rebuilding the film?

I knew a lot about the film from the research I did for Hamilton Babylon. I knew it inside-out without having seen it. But I knew about it mostly from the testimonies of people who supported its right to exist and those who wanted it destroyed. So I was getting a lot of very conflicting responses to what people actually saw — which is the story of censorship, isn’t it? When you encounter really ignorant minds, they are going to invent things to be offended by. And by the same virtue, when people are fighting for the liberty of objects, they are going to find ways to temper what’s truly transgressive about the objective, for better or worse.

So the reconstruction is speculative. I see it as a vehicle for Rob’s voice more than anything. I know that John felt strongly about that text, which is taken from an infamous, anonymous Victorian memoir. Because of his reading of that text being what it is, Rob’s performance is a cherished memory for a lot of people that I know, and I wanted to share that with a wider audience. It gives some suggestions of what the film might’ve been like. But what I’ve done is cut out all the footage that was added to it. There was all this footage that was shot in California to repackage it as a softcore film. What you see instead is just material that was shot in Hamilton, for John’s original version of the film. I’ve arranged it in a dual screen. I’m lacking in things that were really important to the original. We don’t have, for instance, a scene where a couple very, very slowly undresses over the course of 10 minutes. There were all these durational things that were happening in the original that are not present. Hopefully, someday, they will turn up.

Your commentary track for Palace of Pleasure is perhaps the highlight of the entire initial run of Black Zero films. Can you give us some insight into the work that goes into creating such a detailed presentation?

I wrote it over the course of two months. From my experience narrating video essays, I knew the length I had to write to cover a particular period of time. There were points I needed to hit: I had to talk about the relationship of the film’s underlying philosophy to the ideas of Wilhelm Reich; I had to deal with what precisely is being seen when we see the illustration of the Leonard Cohen poem. It might be obvious to other viewers, but it took me a long time to realize what was happening there, with the resonances between Cohen’s poem, “You Have the Lovers,” and the scene of the three figures in bed. That is not an easy conclusion to draw and the film doesn’t draw it for us. When I first saw the film, I accepted what John and others told me, which is that the sound and picture are simply two components that have an indeterminate collision; like some Cageian indeterminate operation. But then, that’s not true, because there’s a reason why “My Generation” plays under these images of free love fantasy and the Vietnam footage. There is a particular reason why we end up with “You Have the Lovers” in the midst of this imagery that suggests the erasure of self, that vanishing third person, the ghost at the banquet. That took me a long time to get my head around.

I didn’t have the foresight to record an interview with John before he passed away. We don’t have that kind of material. I feel bad about it, because I had nine years of living with this restoration and I could’ve done that anytime, and then John died and we don’t have that option anymore. That being said, John was not always the best advocate for his own ideas. If I had John on a commentary track, I think that he probably would’ve just defensively condemned his own film. There are ideas in there that are beautiful, but they are beautiful to young minds. The older and the more world-weary one becomes, the less attractive some of those ideas seem. One can hit a point where the salvation of pleasure and the emancipation of the body cease to be interesting, because they seem impossible. I like to think that what I am doing is something like a surrogate commentary, on his behalf, in his absence. But I do know that he would’ve seen this film very differently than I do.

You recently composed a pair of commentaries for Severin Films’ Blu-ray release of two Murray Markowitz films, I Miss You Hugs and Kisses and Recommendation for Mercy. What do you see as the greatest benefits to your style of analysis with commentary tracks, not necessarily as opposed to, but in comparison with the video essay format or a written essay?

The commentary tracks I’ve done are carefully machined. I like the freedom of visual remix that comes with the video essay as it allows me to explore an idea unhindered by the trivia of whatever’s on screen at a given time. But I also love that aspect of the commentary track, the linearity of it, the fact that it imposes a shape on the course of the discussion. With the Palace of Pleasure commentary track, there were things I could’ve talked about forever, like the connections to Norman O. Brown and Wilhelm Reich, but because there were other things that needed to be said, I had to stop myself. You see a hybrid of these approaches in the shot analysis on the Strange Codes disc because I have the freedom to freeze on images and speak at length, but I am still guiding the analysis along a linear sequence, from one allusion to another.

One of the things I find most intriguing about Black Zero is the willingness to treat short films as main attractions. It’s rare to see a short, or at least a non-standard feature length film, receive a standalone home video release, and you have already released two films that are well under an hour in length. This may be an obvious question, which you answer through the very act of releasing Strange Codes and Palace of Pleasure, but what are the merits of shifting the standards in regards to short films on home video?

The whole notion of categorizing films as ‘shorts’ and ‘features’ is something I try to move away from. We might talk of paintings in terms of canvas size or scale, but if we fixated on big canvases and little canvases as the primary experience of a painting, we’d be idiots. Unfortunately, film culture has fixated on scale in ways I’m glad to contest: I think of my friend Bruce Elder’s films, which are often talked about for their epic length but rarely for how dense and rich they are as experiences. When I do episodes of Art & Trash or other video essays, I deal with both short films and feature films and I don’t really draw a distinction because for me it’s more about the experience a work offers us.

Strange Codes needed this treatment. It’s an obscure film, and not just in the sense that it’s not known. It’s obscure in its conception. It demands so much context and contemplation that to put it on a disc on its own, for me, would easily demand a “feature’s length” worth of rewatches. I would say that about most short films anyway, but in this case, the only way to get the full experience is to watch it again and again. It may still seem mysterious on the tenth viewing, but then, it may always seem mysterious.

With Strange Codes, I felt that what we were dealing with was a miraculous miniature, made by a great artist and overdue for this kind of treatment. That being said, my dream release would’ve been to do the complete films of Arthur Lipsett and have seven shot analyses on the disc.

For each of these films, there is a sense of strangeness, strange being a good thing, obviously, and overloading of the senses that seems to be an important part of the experience these films offer. In giving such detailed critical attention to these rather unorthodox films — particularly in the case of Strange Codes and your feature length shot-by-shot breakdown of the 23-minute film — how do you reach a balance in your video essays and analyses that gives insight into the films, their inner-workings, and historical backgrounds, while keeping a sense of their mystery intact?

My goal is to be able to share both data and interpretation. One can have an interpretive or analytical approach, but the important thing to me is that I am somehow enhancing the experience of the work in what I bring to it and what it brings out of me. There is this question of whether close analysis exhausts the mystery of the work. That’s an important question with Strange Codes, as I think that the film, in some very odd way, asks us to exhaust its mystery. Yet at the same time, its mystery is inexhaustible. We could look at it all day and provide analysis of its contents and elucidate the meaning of every note, every scrap of paper and every image, and still find ourselves bereft of a clear interpretation because so much of what exists there is contradictory. So I knew that no matter what I did with it, I would be protecting the core enigma of the film, because there was nothing I could do to harm it.

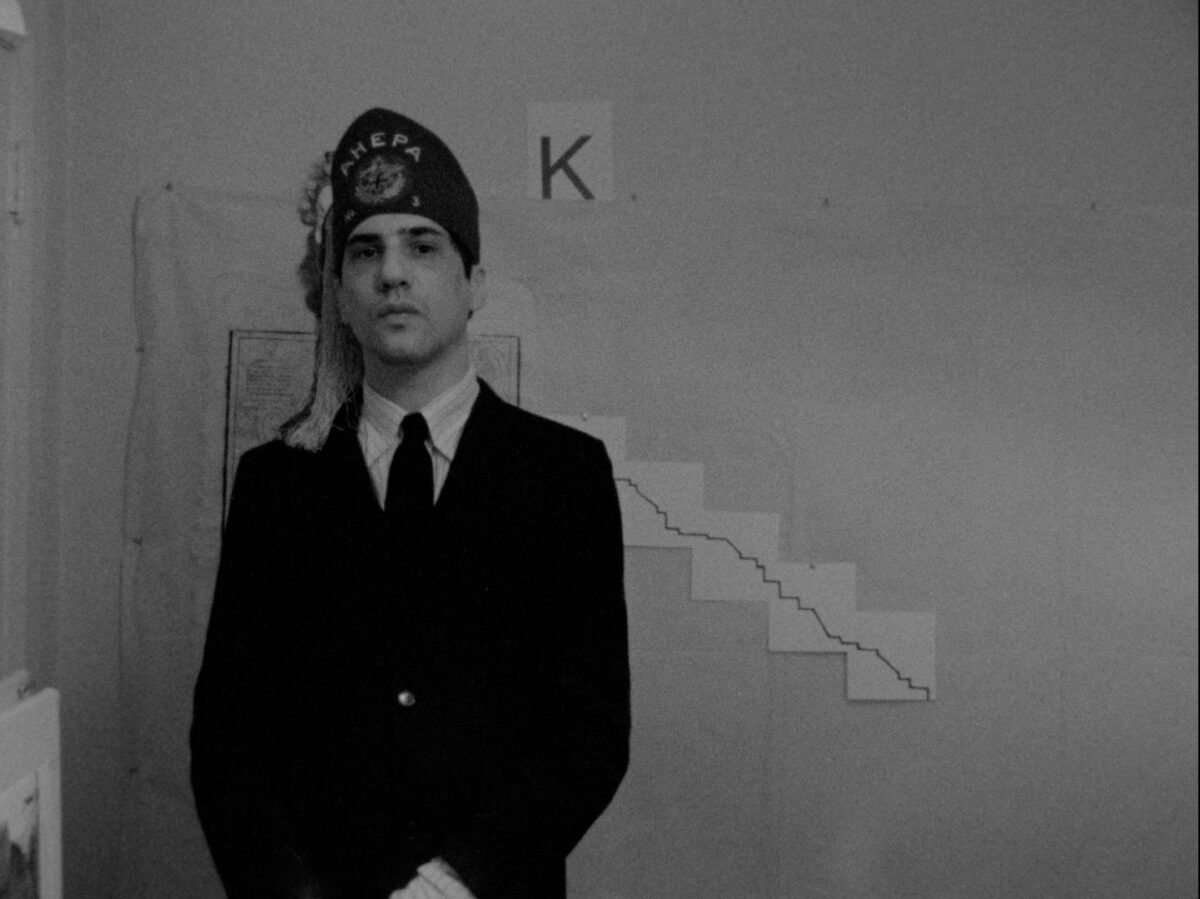

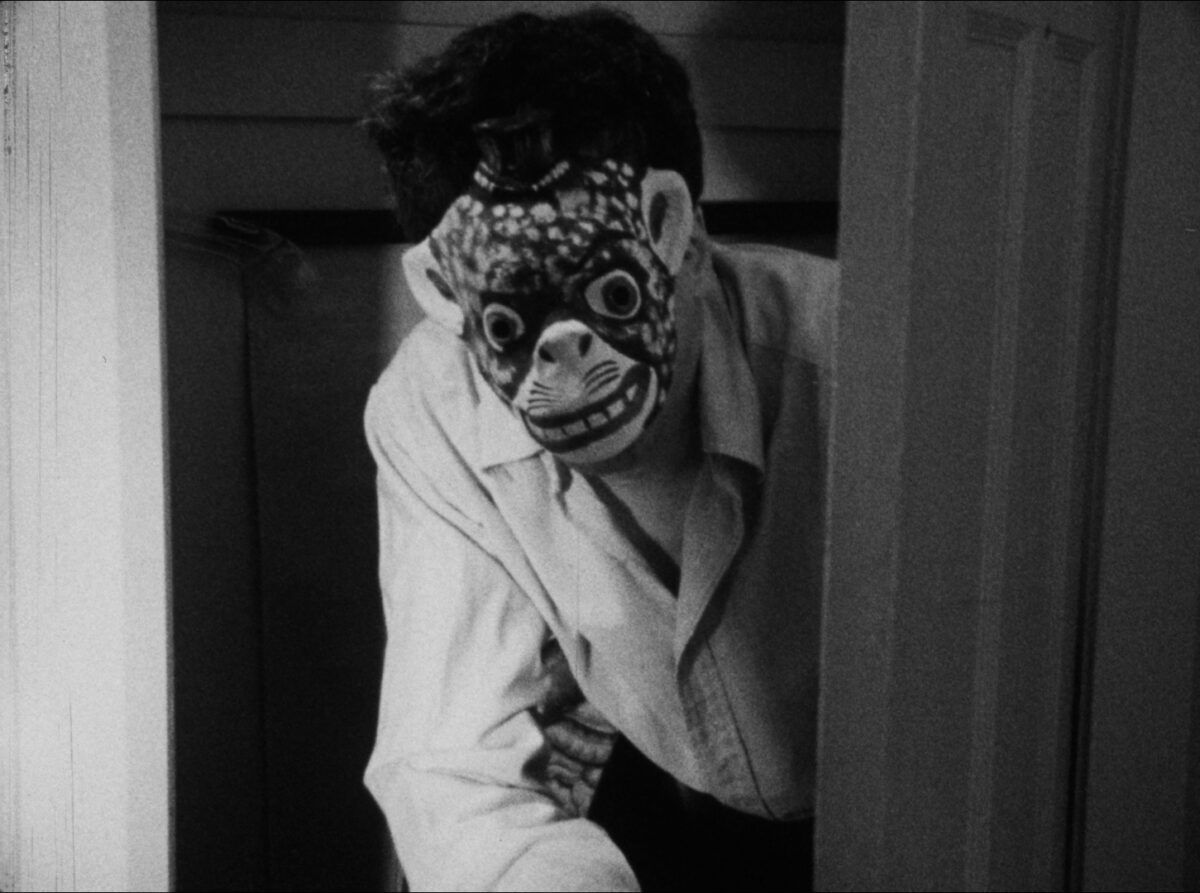

It doesn’t hurt the film, for instance, to reveal that Lipsett considered his character with the little fez hat to be an archeologist, as opposed to a detective, which some commentators have labeled it as. It doesn’t hurt to further this analysis by saying Lipsett made notes about Heinrich Schliemann — that was his ideal of archaeology — and it’s this comical, absurdist ideal, the archaeologist who destroys what he loves, leveling layers upon layers of an ancient city in search of something that isn’t there. That’s the role he’s playing. But even if I make these observations and explain what I think he’s doing, it’s somehow shielded from ruin. There is nothing that I can do that will spoil the effect he has created.

There is an element of advocacy to the work Black Zero is doing as well. Your release of Strange Codes is a work of corrective history in many ways. Arthur Lipsett has certainly left his mark on the history of cinema, but remains a misunderstood figure. Where does Strange Codes stand in his filmography and what are some of the misconceptions about him and his work that you are trying to combat with this release?

I’m currently preparing for the publication of my book on Arthur Lipsett. It’s been a long time coming. I’ve been working on it for seven years. Lipsett has been widely misunderstood as a tragic figure — he was tragic, but his films do not have purely tragic dimensions. This is not necessarily universal, but I often encountered this idea when I teach his films and when I travel and show them to people who have already seen them: they seem to have this entrenched idea that, since he died by his own hand and because he was known to have suffered from terrible mental illness in the final decade and a half of his life, that this was something that we can see anticipated in his films, that they are works about how horrible the world is. He was not a misanthrope. He was a bright, funny guy who had an absurd sense of humor. It was a sense of humor that people who knew him seem to have been aware of, but for some of them, it took on a different dimension in light of his tragic end.

The truth of Lipsett, I think, is that he was an absurdist in anticipation of the era of Monty Python. A beatnik who was visionary, but who was also a holy fool. And when I say he was a holy fool, I mean a holy fool of the order of the “mad children of soda caps,” of Lenny Bruce, The Fugs, Abbie Hoffman, Allen Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso, the maddest fool of them all. I see his films as being deeply funny, but he had this tragic life story: his mother killed herself in front of him, there are various accounts of his sense of alienation from his father, but also, he grew up Jewish in Montreal in the immediate postwar era, when you had anti-Semitic agitators causing riots in the streets. He was someone who had seen all the ugliness of the world, and he responded to it with comedy.

Strange Codes, to me, is a funny work made by a funny guy who happened, unfortunately, to be going through something in his personal life that was making him sick. I happen to be of the mind that his sickness plays a minimal role in the film, and is not an explanation for the reasons that people can’t interpret the film. The film doesn’t give us a roadmap, but that doesn’t mean it’s just an act of madness. I think that people can’t analyze the film because they aren’t trying hard enough and that Lipsett’s mental illness is an easy scapegoat and an excuse so that people don’t have to think about what’s going on in the film. They can just say that, it’s a crazy guy going crazy. And it’s not. I hope that with my shot analysis, I’ve proven that it’s not.

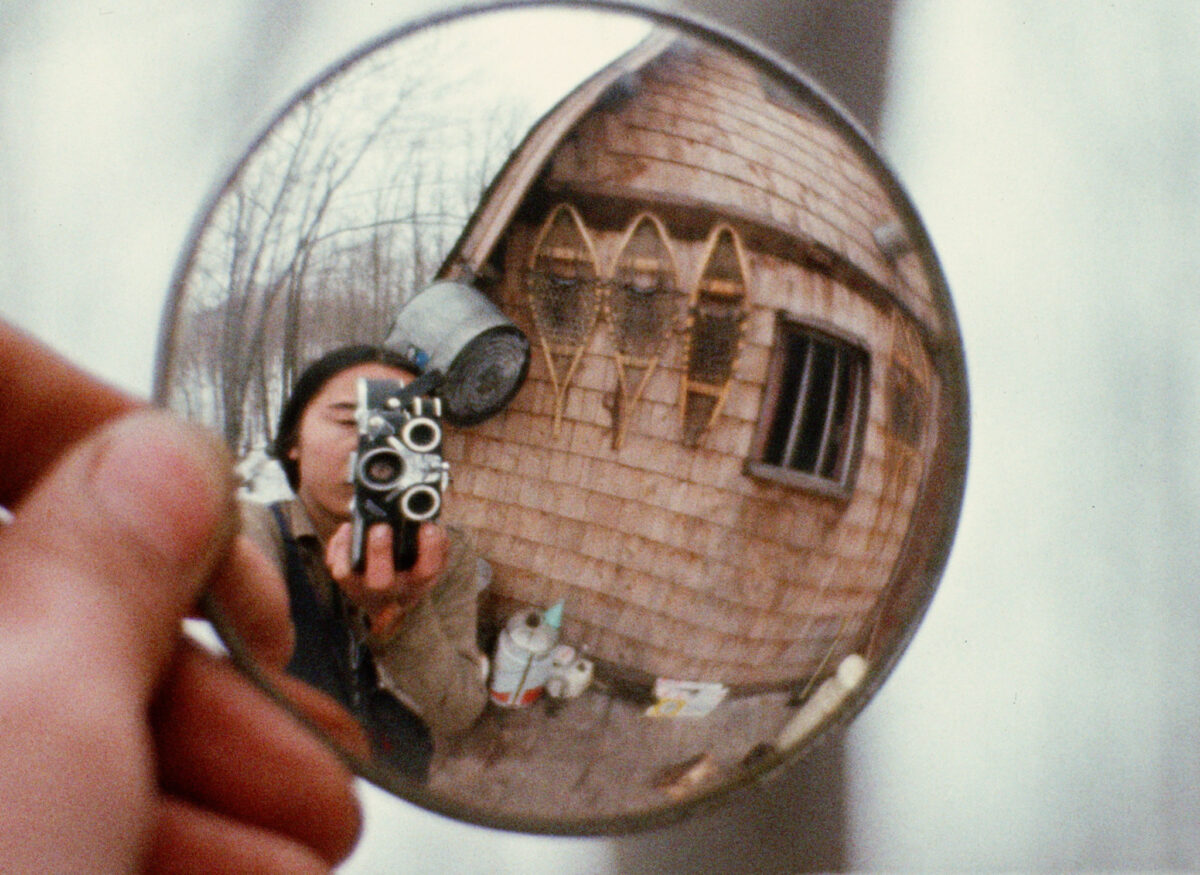

You’ve described your Everything Everywhere Again Alive release as a collaboration with the director, Keith Lock. What was the experience like working with the filmmaker himself on a release of his own film? Were there particular aspects you both aimed to highlight through Black Zero’s presentation?

Keith has such a clear understanding of the film’s meaning, its power, and where it comes from in his aesthetics. It’s a diary, but a diary that is constantly attending to the fact that it’s also a film, and conscious of the limits of observation. Our desire in making this disc was to develop something that was as comprehensive as possible. Keith’s audio commentary is particularly special: he carefully prepared a text that deals with situating each scene in context so that we understand who is present and what kinds of motivations were informing his creative decisions, both in the moment and during the editing.

In terms of a collaboration, Keith and I have known each other for a long time. He is an amazing storehouse of knowledge of what’s happened in Toronto. He’s been present in the scene since he was a teenager in the ’60s. He approached me when he was putting together a book that was to be partly a memoir of his experiences in the scene, and partly a critical analysis of the history of Toronto independent filmmaking. That book unfortunately didn’t happen, but out of the meetings we had, Keith and I became friends.

At some point, when I began to think about Black Zero as a company, it seemed like a foregone conclusion that Everything Everywhere Again Alive would be a flagship release. To the tiny community who knew about it, it was like this monumental autobiographical film. It was seen pretty widely within Toronto when it came out, so people who were in the scene in the mid-’70s knew about it. As a result of that, a couple of teachers took it up as a cause and continued to teach it over the years to generations of students. These teachers were R. Bruce Elder at Ryerson, Rick Hancox at Sheridan College, and Richard Kerr at Concordia University. Outside of classrooms, it was a film that had been long out of circulation. The only prints were in Keith’s own possession and the negatives were at the Library Archives Canada. The work that the Archives’ staff does, at the Gatineau Preservation Center, is just astonishing. I consider them a community partner on some of these releases because of how indebted to them I am for the work that they’ve done.

The disc had a long development process. Because of this, while we were waiting for things to fall into place, we were able to make bonus features out of things that came up. We went to the site of the commune (“Return to Buck Lake”), I was able to sit with Keith and do a long interview (“A Circle in the Wilderness”), and, of course, the restoration of Keith’s 8mm film Going, which is on the disc as well. All those things just came up organically because we weren’t ready to go yet, so we kept adding new things into the mix. And Keith is the easiest person in the world to collaborate with because he is incredibly creative and has enormous reserves of patience and compassion. Spending time with Keith is one of the best things that has ever happened to me as a filmmaker, because he is such an inspiring person. I just had him as a guest in a class I’m teaching at University of Toronto this term called Local Film Cultures. I asked him if he would come in and talk about some of the things that had been in his book. The students were taken aback with the poetic bearing of his spirit, especially because he is someone who can speak to challenges they understand in more general terms, like the challenge of being a Chinese-Canadian filmmaker in a racist world and in a racist society; the challenge of being someone who is interested in art in a society that largely rewards lowest-common-denominator commerce. For all those reasons, I hold Keith in such high regard and I am delighted that we can share this film. The disc is a very clear articulation of the Keith Lock that I know, his generosity, and patience. Maybe that’s what happens when you spend a year chopping wood and carrying water.

All of these Black Zero films have a meditative quality to them. They are all films that are best seen after midnight. They are films that open onto other forms of consciousness. Though they look very different from each other, Everything Everywhere Again Alive and Palace of Pleasure have a lot in common. They are both about looking critically at life as-it-is and at life as-it-may-be.

You write and compose video essays on your website, Art & Trash. As the title suggests, you give equal treatment to underground art and exploitation films. What led you to create the website?

Art & Trash came out of a few pressing needs of mine: to find a forum for talking broadly about cinema, to find a shared use of my filmmaking skills and critical skills, and to have a public portfolio of my work as a teacher. I started it during the pandemic, and it’s grown to 23 episodes of the main series and 10 episodes of the subseries, Detours, on film noir. I’ve found some people are really sensitive about the use of the word ‘trash’, as if it’s a pejorative when we talk about cinema… but I actually think it’s simply comprehensive. You can use the words exploitation and grindhouse, and I would fold into that cult and psychotronic… but there isn’t a useful comprehensive term for all of this cinema, something that encloses both commercial and transgressive narrative cinema that exists within a separate continuum from the polite world of moviegoing. I never truly saw a distinction of taste between art and ‘trash’, but I do see a division of intent, sometimes between conscious and subconscious character, or between intentional and accidental form. I’m not really interested in categorization, I’m interested in rich experiences, and the experiences may be different, but I’m as compelled by what I see in The Beast with 1,000,000 Eyes as I am by what I see in Quick Billy, and I want to treat Ray Dennis Steckler as seriously as I would treat Christopher MacLaine. I don’t think art and trash are equivalent because I don’t think any two movies are equivalent. Movies and filmmakers should be considered, analyzed, and judged on their individual merits.

Thus far, what have been some of the biggest challenges in forming and getting a home video label off the ground, especially considering the highly specified films you are releasing?

I had already accepted that this would have a narrow market, so it’s a slow journey to sell copies, and I saw that coming. But I have been wonderfully surprised by the warmth and support I’ve received from an audience that is eager to see and learn about films that are newly available to them. I see the primary challenge — and pleasure — to be that of audience-building and outreach. My reason for starting Black Zero was always to be able to share these films and to introduce an audience to new experiences. I don’t consider the fact that there isn’t an inherent audience for these films to be insurmountable; on the contrary, it’s an opportunity. If someone purchases Palace of Pleasure having never seen an experimental film before, and they discover something in it that drives them to experience more, and they turn around and buy Kino’s new release of Bruce Posner’s Silent Avant-Garde restorations, or Re:voir’s release of Michael Snow’s Presents, then I’ll be very pleased. As a filmmaker working in this tradition, I want to be an ambassador for it. The diversity of experiences an audience can find in underground movies is infinite. Being introduced to these films has been one of the great joys of my life. I want to pay that forward.

How do you hope to push yourself and Black Zero with future releases?

I feel I pushed pretty hard on the first wave of releases! I want to do more of the same. The next wave of Black Zero releases is coming together — slowly — and those discs will involve more voices. It was never my intention to dominate the bonus features on the first round of discs. I just happened to be there. But I want there to be room for collaboration wherever possible, and to continue with video essays, commentaries, documentaries, liner notes, because if we can keep that up for films that have such secret histories, that will support the cause of film education.

Follow this link to learn more about Black Zero’s

collection and purchase Blu-rays

Explore the Art & Trash archive

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)

- One of Hofsess’ crowning achievements was his role in organizing the 1967 Cinethon in Toronto. It was a three day, 72-hour festival of Canadian and American underground film that he had helped to coordinate and conduct. Broomer’s father’s band, the Stu Broomer Kinetic Ensemble, was present at the event, performing the live score for Joyce Wieland’s happening Bill’s Hat when it premiered there.

- Upon Hofsess’ death, Broomer composed a eulogy that was published in Hamilton Arts & Letters called “John Hofsess: Man in Pieces.”

- Broomer: “[Fothergill] was a friend of John’s in the ’60s and ’70s and a great scholar of English diaries. He was an academic of a particular era, who deeply believed in the cause of a common culture. He was the kind of guy who could give you these amazing lectures on Death of a Salesman and Shakespeare.”