Made by an entirely African American crew and presumed lost for decades after the death of its director, Cane River finally obtains the distribution it deserves

Humankind may not be doing the best job at ensuring its own survival at the moment, but we can at least be proud of the heroic efforts being made by a select few at preserving and unearthing forgotten gems in our film history. A handful of talented and, above all, passionate archivists and home distribution companies have been presenting vital works that have been misjudged or carelessly swept aside for decades. Whether it is Milestone’s recent restorations of long unavailable films by African American filmmakers — Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1983) and Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground (1982) — or Vinegar Syndrome’s unearthing of Bill Paxton’s odd screen debut in Taking Tiger Mountain (Tom Huckabee and Kent Smith, 1983), many films that were never given a fair shot are finally receiving the technical care and critical attention they deserved long ago.

Horace B. Jenkins’ Cane River is just such a film. Jenkins was a successful documentarian who died in 1982 shortly after finishing Cane River, his narrative debut that was believed to have been lost until 2014. IndieCollect has completed a 4K restoration of the film, which will be released for the first time after almost 40 years. It is currently making a theatrical run across the United States with a home video release from Oscilloscope Laboratories to follow.

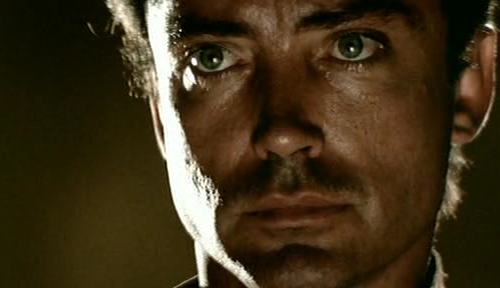

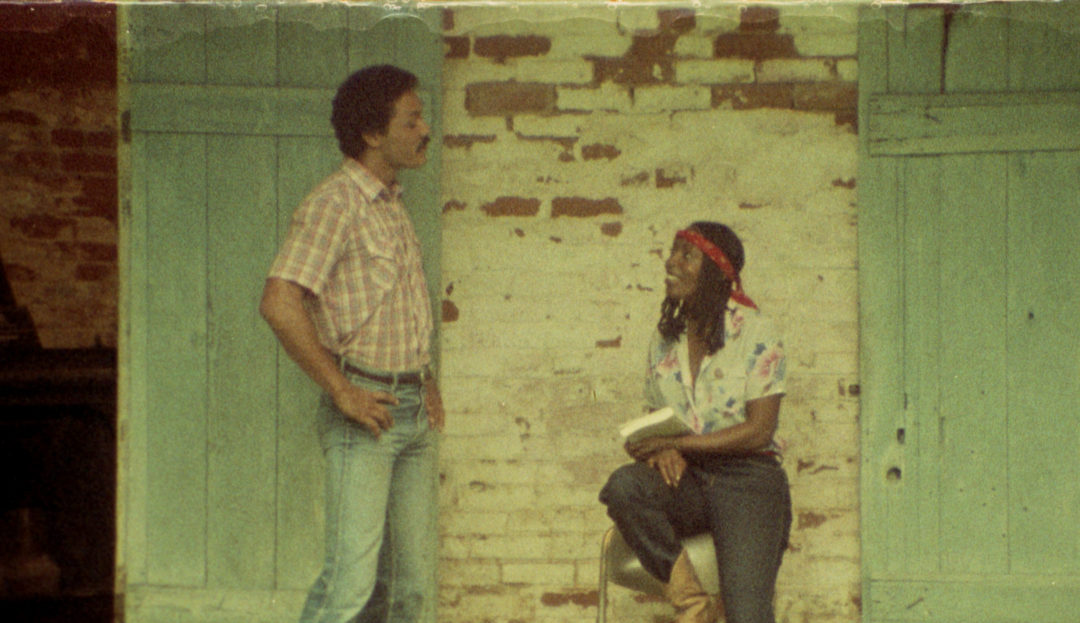

Peter Metoyer (Richard Romain) is a star college athlete who returns to his Louisiana hometown in Natchitoches Parish after turning down a professional football contract in New York. He desires to work on his father’s farm and become a poet. Jenkins gives us our first glimpse of the quaint life Peter expects to return to in the film’s opening montage of his bus ride home: We see Peter playing in local sporting events with seemingly the whole town looking on and cheering; he swims at the local river dock with friends in compositions reminiscent of an Eakins painting. He soon meets a young woman named Maria (Tommye Myrick), who is from a more disenfranchised black community than Peter and his lighter-skinned Creole heritage. Maria lives with her single mother and brother and works as a tour guide at a historic plantation that was owned by Peter’s distant relatives. She plans to attend college in New Orleans and leave behind her small town roots. When she and Peter are spotted together, word reaches Maria’s mother who warns her against Peter, for his ancestors were not just wealthy black land owners, but a family of ex-slaves who owned slaves and supported the Confederacy.

While much of the film involves the couple in tender, even idyllic, romantic moments — riding together on horseback or playing around a swimming pool — Cane River creates a unique tension where distant past and near future cause equal strain upon Peter and Maria’s love. Peter’s complicated Creole heritage taints Maria’s mother and brother against him. They see him as a troubling companion for the young woman. Maria’s dreams of going to college and becoming a self-sufficient woman in a big city also don’t match Peter’s idealistic vision of a poet’s life in the country. They each romanticize exactly what the other is trying to escape from.

The film’s supporting cast is often more interesting than the love story at its center. Peter’s sister has a fantastic first scene with Maria, in which she not-so-subtly grills his new girlfriend about her religious and cultural background. Maria eventually sends it right back by giving the nosy sister twice as much information as she wanted, until they both break out in laughter.

Maria’s brother, whose name is “Brother,” is an old high school football opponent of Peter’s. He is an athlete who didn’t have the opportunities of the better-off Peter. Brother still works out like his old high school self — he even wears wrist weights to the dinner table — but he is stuck working an exhausting job and drinking himself to sleep at night. Brother is a figure who perhaps could have been a successful athlete, but he was needed at home to help his family pay the bills. Adding to the pressure upon Maria, Brother is also responsible for raising a portion of her college fund. While little drama is made of it, his presence in the film creates a striking contrast to Peter’s tossed aside professional football contract and his self-centered urging for Maria to pack her own ambitions and mold into his desire for a carefree farm life.

It is a strength of the film that the most urgent dramatic elements of Cane River remain in the background. For instance, Jenkins introduces a subplot of Peter making efforts to reclaim land stolen from his mentally ill aunt by greedy, manipulative developers, but the film only takes it as far as Peter meeting with a lawyer. At times the historical aspects come across as slightly didactic — as when Peter recounts the research he has done on his family history to Maria or when the lawyer gives a statistical account of how much land has been stolen from African Americans over the centuries — but Jenkins’ light and mostly un-melodramatic approach allows these issues to stick out without overshadowing the romance at the heart of the film.

Cane River ultimately explores the deep, lasting scars of African American history and the threats many black communities face to preserve their heritage. Jenkins shows how rifts and prejudices can engrain themselves within a culture’s memory for centuries, disrupting the joy and romance to be found in the present, while personal histories, the homes and spaces where vivid, life-defining memories took place can be torn down without a second thought for heritage. Much like the film and its eventual re-release this year, Cane River is a story of hope for the future, of people learning to live with and recontextualize the past and approach the future with new eyes.

Purchase Cane River on Blu-ray/DVD from Amazon here

Stream Cane River here

Follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)