Named after Jack Torrance’s job in The Shining, The Caretaker soundtracks the haunted ballroom by warping old 78 records into faded memories

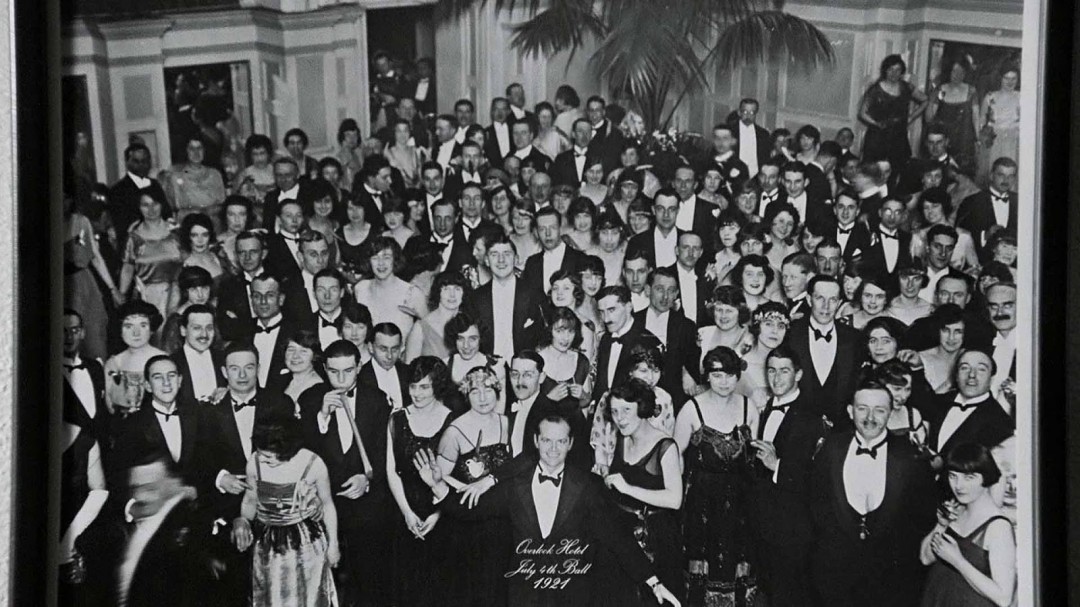

Overlook Hotel. July 4th Ball. 1921 — “Midnight, The Stars And You,” the popular foxtrot song recorded by Ray Noble and His Orchestra in 1934, rises up on the soundtrack, as if we are getting closer to the party in mid-swing in the Gold Room. With the final, fateful shot in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) — dollying towards the commemorative photograph on the lobby wall of Jack Torrance’s grinning face front and center amongst a crowd of partygoers — the music of the British dance band era was subsumed by the horror genre. Often referred to as the “Golden Age of British music,” which stretched from the ’20s through the early-’40s, this era feels like it was always haunted, denizens from a generation decimated by trench warfare and mustard gas waltzing the nights away with another World War on the horizon. Al Bowlly, the rising star who sings the forlorn lyrics of “Midnight, The Stars And You,” died in that next Great War when a bomb landed on the house he was in. His story stands in for an era of beautiful and damned decadence frozen in the purgatory of these woozy, mid-tempo numbers.

Nearly two decades after The Shining reset the loop of the Overlook Hotel, Manchester-born, Krakow-based leftfield electronic artist Leyland James Kirby took up the mantle as The Caretaker, a nod to Jack Torrance’s job title. With the music he made under this moniker, he followed the thread left hanging by Kubrick, sampling Ray Noble, Al Bowlly, Turner Layton, Russ Morgan, and many of their dance band contemporaries. He both reclaims this music — appreciating these songs for their craft and themes — and amplifies the spectral aura. The Caretaker’s molten, somnambulant debut, Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom (1999), is a whole album of songs that might have played in The Shining’s Gold Room, hollowed out and stripped of their celebratory spirit.

Kirby hails from the epicenter of indie-rave and acid house. His career started during the peak of UK garage and 2-step. You can view his earliest work, from his early zip-lock bag experiments to his first run of records as The Caretaker to The Death of Rave as V/Vm, as reactions to the heady music he’d absorbed in the rapidly evolving UK scenes. The Caretaker albums anticipate imminent underground styles of dubstep and future garage — in tone and texture if not style and structure. Haunted Ballroom is foreboding and cavernous, with forays into sluggish carnivalesque ditties, roaring noise, and digital glitch. The discernable melodies feel miles away, distant sounds or distant memories that are beyond your grasp. It’s big band music filtered through the prisms of modern classical, ambient, plunderphonics, and hauntology. In your mind, the echo and delay is almost added unconsciously before any electronic manipulation is applied. Kirby coaxes this ghostly aura to the surface, tapping into the music’s pathos by adding warp, texture, and repetition to dusty 78s.

Haunted Ballroom closes with an oneiric reprisal of “Midnight, The Stars And You,” now scuffed and reverbed into oblivion. As the sound of The Caretaker progressed through the next few albums, so did the complexity of Kirby’s thematic explorations. The Caretaker evolved from an exercise in atmospheric nostalgia to a harrowing investigation of memory disorder, cracking the project wide open with the epic Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia (2005). Kirby’s music as The Caretaker is quieter and more introspective than his constellation of other projects — V/Vm, The Stranger, myriad solo works under his own name — gently weaving through the labyrinth of the mind while preserving a sense of dread through jump cuts, record skips and pops, surface noise, and passing squalls of feedback. He amplifies analog sounds through digital processing, fusing modern and antiquated technology. The project reached a stunning clarity on his ninth long player as The Caretaker, An empty bliss beyond this World (2011), released on Kirby’s own boutique label, History Always Favours the Winners (which supplanted his venerable V/Vm Test Records).

An empty bliss was recorded during a period of chaos and exhaustion, a transitional time in Kirby’s life when he was living and working in Berlin and ensnared in the city’s nightlife scene. The record smooths out the more jarring detours of earlier LPs and locks into a sustained reverie, careening down the echo chamber of a vanishing mind. The sufferer is experiencing a blissful oasis, an eye in the storm of their cognitive decline. In this fugue, they recall the music of their youth, the indelible big band swing music that accompanied formative gatherings, the faint outline of the happiest times of their life. Kirby’s music as The Caretaker touches on many different cognitive failings: the breakdown of short-term encoding, progressive long-term memory degradation, ruminative memory loops, rewritten, and mutating memories. Kirby’s music arguably has the power to replicate a fraction of these feelings in the mind of the listener. It’s disquieting to think about knowing that you’re losing your mind. It’s equally disturbing to consider losing your cognitive faculties and not being aware of your deterioration. An empty bliss teeters on this precipice separating awareness and acquiescence.

An empty bliss is, by design, the most accessible of The Caretaker albums — both modest in its length and melody-forward. It’s the release that rests in the middle and stands for the whole of the discography. The challenging aspects of the project — deeply submerged sonics, forays into noise, long stretches of near silence — mostly fall away in favor of fragments resembling actual self-contained songs. From Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia (2006) through Persistent repetition of phrases (2008), the samples pushed closer to the surface. An empty bliss is a leap forward. The sound is rich and the samples are crystalline. The inherent flaws of the source material and the electronic manipulations are all rendered with care and tactility. It has been hailed as a landmark ambient release, one of a handful of high-water marks as the genre exploded this century. There are still disorienting elements throughout: phantom banter in the background; off-balance panning; two title tracks; record skips; abrupt song endings; intoxicated, decelerated melodies lagging behind the meter. But you feel wrapped by this music, enveloped in a wonderful haze. It carries you along on a stream of consciousness.

Earworm phrases — like the lilting horns of opener “All you are going to want to do is get back there,” the drawing room piano of “Moments of sufficient lucidity,” the lightheaded muted trumpet on “Libet’s delay,” and the drunken waltz of “camaraderie at arms length” — stick in your mind, showing Kirby’s knack for selecting evocative samples and tapping directly into your cerebral cortex. These big band numbers are not big band numbers anymore; they’re intimate and stripped down. Rather than reverberating through a packed ballroom, this album feels like late-night parlor music that’s played as the party draws to a close. Interludes — like “Mental caverns without Sunshine” and “Pared back to the minimal” — gesture toward the drift, drones, minimalism, and modular synths of more traditional rainy-day ambient like Stars of the Lid or Bing & Ruth. An empty bliss is largely drumless and beatless, leaning into piano parts with the occasional brass and nearly unrecognizable string instruments that diffuse in the mix. In spite of its gloomy atmosphere, the music is jaunty and tuneful, making the record compulsively listenable. An empty bliss is full of simple music-box melodies that rise and fall, that lure you in and entice you to get lost. Gentle refrains — like the impossibly alluring solo piano of “A relationship with the sublime” — invite you to unconsciously close your eyes and anticipate the resolution of the melodies. Sometimes it lands; other times it’s withheld.

Following the breakout of An empty bliss, Kirby charted The Caretaker persona to its demise. He crossed over into film scoring with Patience (After Sebald) (2012), created for Grant Lee’s film essay about German writer W.G. Sebald and his most famous work, The Rings of Saturn (1995). Then Kirby set about crafting his opus, Everywhere at the End of Time, a six-part cycle created and released over a three-year period from 2016 to 2019. Patterned on a mind experiencing dementia, from its earliest stages to the point where the person succumbs, the cycle locates the logical point of no return for The Caretaker, where the decay methodically, systematically, agonizingly overwhelms the melody. Everywhere at the End of Time even had a brief, strange viral moment on TikTok in 2020, with users challenging each other to sit through the album’s crushing six-hour stretch in a single sitting.

Music has been shown to awaken parts of the brain that are not impacted by dementia and evoke responses and brief moments of reconnection with loved ones. This character at the center of The Caretaker’s music is experiencing a sense memory rush on An empty bliss, their faded nostalgia washing over them before the memories are inaccessible. The project as a whole, and the momentous Everywhere at the End of Time in particular, strongly recalls William Basinksi’s masterpiece The Disintegration Loops (2002). UK artist Burial stands out as a kindred spirit, his nocturnal, grayscale mix of jungle, garage, and dubstep mirroring Kirby’s moody soundscapes. And Kirby counts the likes of Andy Stott and Demdike Stare as confidants and collaborators. In fact, The Caretaker was born after a trip to Brooklyn with Sean Canty and Miles Whittaker and a hungover outing at a local record store selling 78s on the cheap.

Kirby’s reputation as a jokester and an unpredictable performer precedes him. He dislocated his kneecap on stage in Belgium once, and had to bang it back in place to carry on with the show. But he rarely performs anymore and when he has played The Caretaker live, he suppresses his ego and diffuses the music. The playful surrealism of Kirby’s work is perfectly represented by happy in spite (2010), the painting used for An empty bliss’ beautiful cover art. Created by Kirby’s longtime album art collaborator Ivan Seal, the shadowy painting of a room-filling boulder, or possibly a mass of clay, with a matchstick jutting straight out clearly recalls the distinctive style of Belgian surrealist René Magritte, in this case, La Chambre d’Écoute (1952) crossed with Le Château des Pyrénées (1959). Seal captures the sentiment of the music: gloomy, slightly menacing, more than a little humorous, and reliant on recontextualizing familiar pop-cultural artifacts. The paradoxical, tongue-in-cheek song titles of An empty bliss and many other Caretaker releases indicate that these are works consumed with the concepts of enormity and loss but also mimetic enigmas and cosmic absurdity.

Working with public domain raw materials, An empty bliss measures the half-life of popular culture. Kirby is obsessed with how technology and the collective unconscious cannibalizes music and eras. He frequently name-drops the short-lived series Pennies from Heaven (1978) as a key influence, and his work draws from certain sectors of horror: The Shining most directly, but also John Clifford and Herk Harvey’s foreboding, atmospheric Carnival of Souls (1962), as well as Angelo Badalamenti’s work with David Lynch. The inevitability of The Caretaker’s subject matter harbors a primal terror. What makes us who we are? Our memories and experiences? Our perspectives and beliefs? Our desires and dreams? What happens when the foundation that supports this complex neural network erodes? The Caretaker faces down the inescapability of our demise, the certainty that each individual mind is eventually wiped clean. It taps into our deepest collective anxiety: that our bodies and minds will expire, that our accumulated experiences will fade, and that one day we will be long since forgotten. The longer we listen, the deeper we sink into this solipsism. As lovely and sweet as the music often is, it’s off-putting to consider a time when the half-remembered music we used to listen to is all that remains.

“The advantage of a bad memory is that one enjoys several times the same good things for the first time,” reads the Friedrich Nietzsche quote on The Caretaker’s Bandcamp page, hinting at the wry, philosophical persona that pokes through the din. The combination of repetitious decay and mischievous rhythms makes An empty bliss ideal mood music for autumn, when the air is thick with dead leaves, creeping chill, and the memories of sunny gatherings. The sound of a dull needle on shallow grooves, combined with reverb and the veil of white noise, creates the sensation of an out of body experience, of observing your memories behind glass — a formless seasonal melancholy. An empty bliss is not a party-starter, exactly; it’s dreary and sullen — desaturated tone poems. But this was party music in its heyday. Now these songs are ghosts of bygone good times, metaphysical melodies for one final spin across the dance floor inside a crumbling mind.

Find An empty bliss beyond this World on Bandcamp

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Oliver on Twitter

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.

Find the complete October Horror 2022 series here: