Split Tooth’s 31 Days of October Horror series continues with George Romero’s vampiric masterpiece

It’s not easy to research incels. That’s not because the involuntarily celibate community lacks for an online presence. From what I understand, they occupy fairly large and fairly prominent sections of many mainstream sites; a subreddit called r/IncelSelfies is having a moment on Twitter as I type this. It’s just one of many forums (again, from what I understand) where mostly white, sexually frustrated, performatively heterosexual men meet to degrade women, decry relationships and declare their own commitment to rage, resentment and — eventually — violence.

No, the obstacles most amateur sociologists face are mostly self-defined. They’re also tied to an interest in self-preservation and self-care. As incels have evolved from punchlines into members of a recognized hate group, they’ve become dangerous even as objects of scrutiny. That old half-joking fear, “Will I end up on a list for Googling this?” certainly runs through my head, and that’s about as benign as incel-driven fear gets. In addition to harassing and doxxing thousands, at least one self-identified incel has carried out a mass shooting.

Despite society’s aversion, incels have secured a considerable level of control over popular culture. With calls for a certain Director’s Cut choking social feeds and a potential new avatar coming to cinemas, they’ve almost begun to exercise a kind of authorship. They’ve made the call for representation and — for whatever reason — Hollywood seems eager to oblige them.

October Horror Day 1: What Ever Happened to Spider Baby?

Whether or not Joker inspires violence, breaks box office records or collects Oscar gold is (troublingly) beside the point. Incels have reached such a ubiquitous position that they’re destined to occupy screens and pages for years. We’ll never, however, read an Op-Ed from an incel. Again, that’s not for lack of outlets. It’s because incels don’t deal in opinion. They operate with a sense of certainty informed as much by the dogma of a more conservative past as the black and white morality of today’s popular entertainment. They’re certain that they deserve to get laid and they’re equally certain that they never will.

Certainty is the chief antagonist of George Romero’s 1977 masterpiece Martin. Like that embodied by incels, it’s a type of certainty born from both Old World sensibilities and new media tropes. While the director considered Martin (John Amplas) just a “mixed-up kid,” Martin himself knows that he’s something far more sinister. He knows this because his family, most specifically his elderly cousin (and new guardian) Tateh Cuda (Lincoln Maazel), knows this. Their cursed family produces vampires just as surely as Hammer Horror produced Dracula films. Martin is not an awkward, orphaned teenager both scared and obsessed by sex. He’s an 84-year-old incarnation of Nosferatu, consumed by a thirst for blood and damned to an eternity in Hell.

Throughout their journey from Pittsburgh to nearby Braddock, Cuda crosses himself and looks at his ward with a mix of fear and contempt. Upon their arrival in the depressed, depressing town, we learn that Cuda’s home is newly-adorned with strings of garlic and even more crucifixes than usual. We’re made to believe that these superstitions curdled into certainty long before Martin became Cuda’s responsibility. “I grew up in this entire thing too,” complains Christina (Christine Forrest). Another cousin, she has lived with Cuda for years and so far managed to avoid internalizing the old man’s beliefs. She dismisses talk of “the family shame” as antiquated while still acknowledging its terrible power to corrupt. “Sometimes,” she cries, “I worry that I’m gonna start to believe all that bullshit!”

Speaking to his skeptical granddaughter, Cuda describes the dangers of certainty. He dismisses her entire generation for placing their faith not in God and tradition, but in “the laws of the few scientists we have been able to discover.” He continues, “People are satisfied. They think they know all.” These blasphemous youths aren’t just keeping themselves in the dark. Cuda suggests they’re making it possible for Nosferatu and “all the devils” to operate. The irony, it seems, is lost on him.

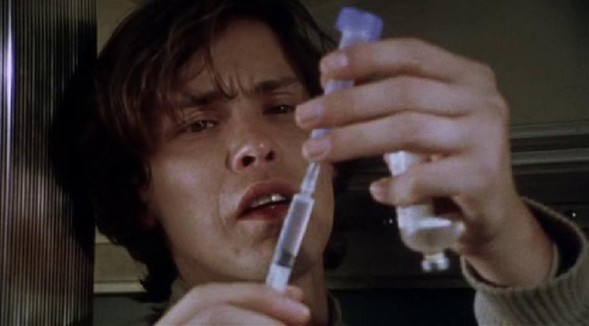

It’s not easy to research Martin. Though it’s justifiably found an audience in the intervening decades — and Romero is said to have adored it — contemporary reviews have so far eluded me. I expect those lucky enough to catch the film during its original run made a meal of its gestures toward the addiction narrative. After all, Martin doesn’t drink blood because he wants to or even because family superstition reminds him that he’s supposed to. He does it because without blood he suffers and gets “shaky.” Today his fixations read somewhat differently. His desperate actions and facility with needles still suggest the behavior of an addict, but his sexuality, at once childishly immature and distressingly violent, calls to mind an especially dangerous incel.

Though he’s violent from the film’s opening moments, Martin doesn’t show an incel’s impotent rage until nearly an hour into the film. After stalking a victim to her home in the suburbs outside of Braddock, Martin is surprised to learn she’s not alone. Her husband has left for business, but her lover has taken his place. He’s also gotten in the way of Martin’s single-minded sexual pursuit. In the incel’s parlance, the man is a “Chad” taking what belongs to Martin simply because he can. “You weren’t supposed to be here,” Martin shouts in vain as he drags the man’s drugged body away from the scene. He then proceeds to drink the interloper’s blood, which satiates without satisfying.

Following this close call, Martin begins dialing into a local radio station. Dispelling myths and describing his struggles, he becomes a local celebrity. He also outlines a worldview that would sound at home in some of the internet’s darker corners. “People are the hardest thing,” he laments, “They don’t talk, not really. They don’t say what they really mean.” Worst of all, they “have ‘the sexy stuff’ whenever they want.” Martin doesn’t just express desire to try ‘the sexy stuff’ for himself, but also suggests that everyone who already has is somehow unworthy.

Martin does manage to fumble into one sexual relationship. His brief dalliance with Mrs. Santini (Elayne Nadeau), a customer at Cuda’s grocery store, provides this deliriously sad film some of its most deliriously sad sequences. She validates Martin, almost fetishizing his halting, inarticulate nature. In an especially tender moment, she even makes note of his single-mindedness and certainty. “That’s what I like about you Martin,” she says, “you don’t have any opinions.” This experience with “the sexy stuff” comes to an abrupt end when Mrs. Santini cuts her wrists. It compels Martin to turn to the one outlet he’s found. In these calls, his attitude toward cinematic vampires appears to have changed. He’s no longer interested in deflating old beliefs, but now takes time to express his disappointment. The incel who fantasized about seduction and possession has come to a realization. He argues, “You don’t need all that.” Why? Because real life isn’t like the movies. Not even for vampires. In real life, “you can’t get them to do what you want them to do.”

For all his efforts to subvert vampire cinema’s usual tropes, Romero ends Martin the only way such a story can possibly end. While reviewers often note how sympathetically Romero and Amplas paint Martin, it’s clear he cannot be allowed to survive. He’s not merely a murderer and rapist, but a murderer and rapist driven by the dictates of a family curse and (perhaps) inspired by cinematic vampires. When Cuda drives a stake into the sleeping Martin’s chest he validates the certainty that both men have carried throughout the film and brings about what Robin Wood calls a return to normality. In this instance, it’s a state of normality that’s rapidly, thankfully fading. Cuda has eliminated one of the last remaining ties to his family’s curse and the dangerous certainty it brings about. He, too, will die soon while his granddaughter Christina writes a new history somewhere far away.

Find the complete October Horror Archive here:

Follow our list of the 31 Days of October Horror on Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)