October Horror 2021 continues with a look at Ti West’sThe House of the Devil, a stylistic anomaly within the continuum of Satanic Panic horror cinema

Three things immediately mark The House of the Devil as a film about the occult and Satanism. First off: the title, obviously. And let it be said, it takes moxie to give your low-budget indie the same title as (arguably) the first horror film ever made, Georges Méliès’ nifty three-minute 1896 magic show Le Manoir du Diable. But Ti West’s handmade 2009 bloody valentine of a film is, if anything, defined by its modesty, a marvel of restraint, negative space, and genre love.

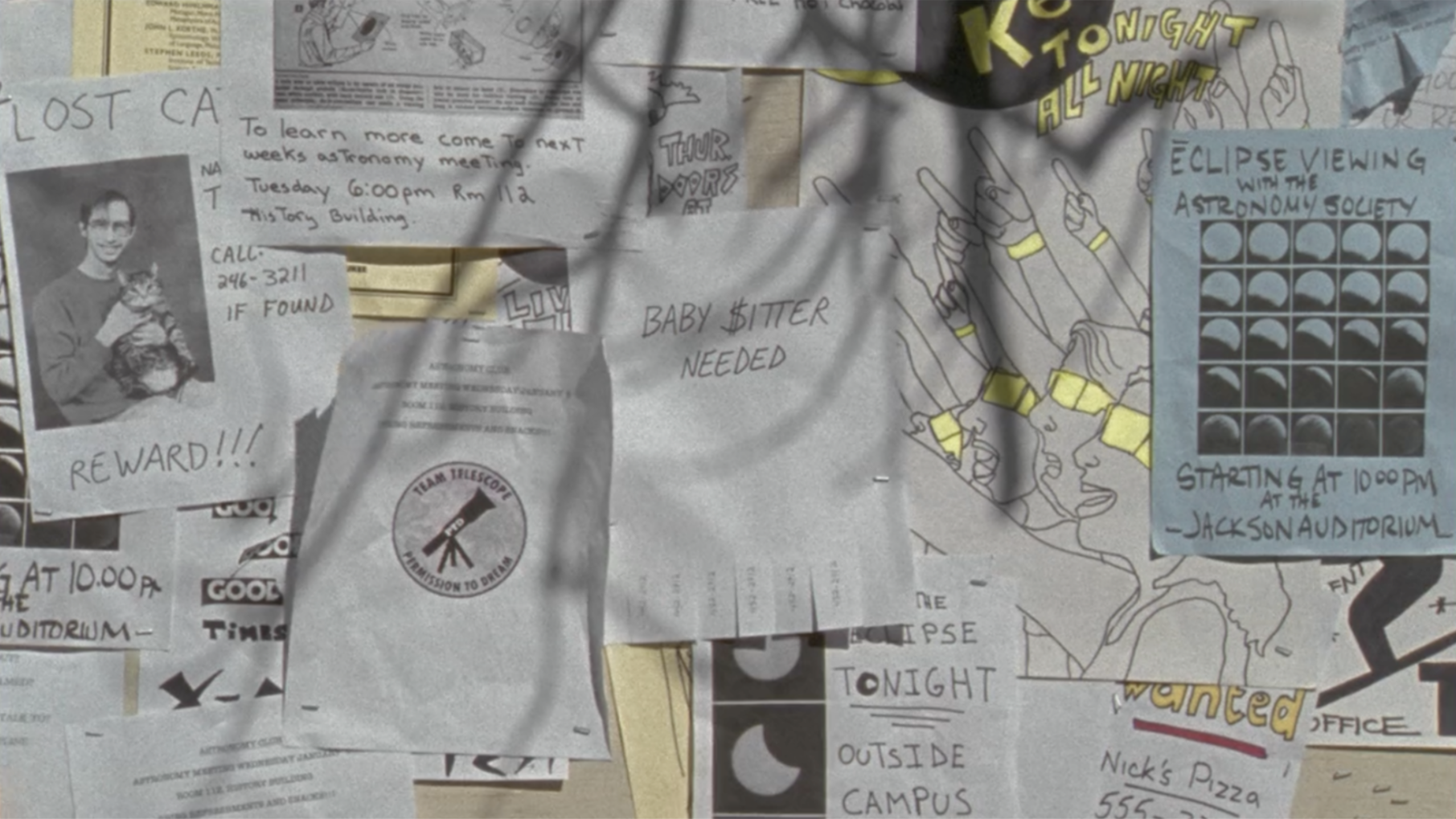

Two, the opening title card: “During the 1980s over 70% of American adults believed in the existence of abusive Satanic Cults… Another 30% rationalized the lack of evidence due to government cover ups… The following is based on true unexplained events.” A brief digression: this is a pretty funny gag. Hell if I can decipher that second line, but why include the bit about government cover-ups in the first place? This has no bearing on the movie. Now it feels quaint; we’ll get to that later. And why make the no-source stats so clean and round — either cults or cover ups? Really? It’s clearly bogus, just a tongue-in-cheek tip of the cap to the lineage of horror films that feign actual events. Moving on. Third, the promise of a full lunar eclipse — a classic trope — which everyone in town is talking about apparently (there’s even a pizza special!). This is mostly for atmosphere; there’s dark ritual significance, but the specifics aren’t too important. Other than these three surface-level context clues, nothing devilish happens until after the hour mark, about two-thirds through.

That two-thirds shift is a beautiful thing, though. Taking a step back, here’s what leads us to this point: Hard up for cash, enduring a sloppy and promiscuous roommate, and lucking into a new apartment with a very endearing, no-nonsense landlord, our protagonist, Samantha (Jocelin Donahue, Insidious: Chapter 2, Orbit gum), plucks a tab from a baby-sitting flier on the campus bulletin board. With her gabby, orally-fixated friend (Greta Gerwig) giving her a ride to the house in the sticks — across from a graveyard, naturally — she meets the towering, cane-wielding Mr. Ulman (Tom Noonan, What Happened Was…, The Last Action Hero), who solicited the advert. He promptly informs her that there is no baby; he actually needs someone to keep watch over his mother, and a previous girl, supposedly, balked at the ruse and the elder care job. Against her better judgement, Sam accepts, negotiating $400 out of the situation — first month’s rent and then some. Mr. and Mrs. Ulman (cult icon Mary Woronov) take their leave to view the eclipse and Sam has run of the creepy house.

Which brings us, eventually, methodically, to that jolt. The camera goes rogue, branching off from Sam’s perspective to the other side of a door she doesn’t enter. On the other side: a tableau of ritualistic brutality, mutilated bodies arranged around and on a pentagram. Until this point, without the other stuff I mentioned, you could mistake the film for a straight thriller, with a lone killer stalking the area around the house where Samantha is navigating an awkward, disconcerting babysitting gig. A sudden, decidedly modern burst of violence clues us into this peripheral threat a third of the way through the movie; and thus, we have a clear, escalating tripartite structure. Squint and you could even find the bones of a comedy, mostly in the spots where Noonan is trying to talk his way around the specifics of the “baby $itting” job.

The House of the Devil occupies an odd place in the continuum of horror films that deal with the Satanic Panic, a period of moral hysteria that waxed from the late-’70s through the mid-’90s. It occupies an odd space among horror films of this century, too. Set in the unspecified ’80s in a frigid, unnamed college town, the film explicitly calls back to the era where this moral panic percolated through the genre. By 2009, Satanic Panic had calcified within horror, a preserved bad-vibes threat to tap into at will. The House of the Devil is a pure exercise in this vein. As a time capsule from the late-aughts, it’s a product of a moment of (relative) optimism, when secularism seemed to be winning out. In 2009, the threat of a satanic uprising had become a distilled ingredient: isolated and untainted, it was homage shorthand, a way to link up with a formative era of exploitation cheapies, minus much of the culture-wars baggage.

It’s a dubious proposition 12 years later; the pendulum has swung back again. Throughout the history of film, “whether presented as allegory or nonfiction, representations of Satan and Satanic worship act as barometers for socio-political trends” (Anthology Film Archives, The Devil Probably). Whereas in the early-’80s, fundamentalist preachers “gained prominence across the country, passing along a literal fire-and-brimstone style of Christianity” (Vox, Aja Romano), today, again, the Religious Right is ascendant, converging with extremist conspiracists and a media landscape on steroids with an unquenchable thirst for sensationalism and eyeballs. Consider, by way of example, the extended Conjuring universe, with its similar reverence for classicist horror styling (and taste for period settings, and feathered hair). Intentional or not, it turns its charlatan protagonists into something like superheroes, squaring off against a malevolent force with a penchant for cosplaying as dolls or nuns. As critic Katie Rife points out, speaking about The Conjuring 3 from this year, “this movie gets into Satanism and witchcraft… [and] kind of tacitly [says] that the Satanic Panic was justified because Satanists are real and they are after your children.” What’s more, converting the skeptics is a recurring trope in the franchise; the latest even brings in courtroom proceedings, which is a queasy concept all things considered. And this iconography is let loose in a sociopolitical climate where conspiracy theories, scapegoating, fearmongering, regressive policing and judicial overreach, and, frankly, viral madness has erupted again. The parallels, between the Satanic Panic heyday and the tenor of the here and now, are striking, with some new mutations: “Many right-wing conspiracy theories that have ballooned into serious threats over the past five years contain overt elements of Satanic Panic” (Vox, Aja Romano). Harkening back to a bygone era where unfounded moral panic ruined lives and communities, and sort of validating those same perceived threats, is dicey at best.

The House of Devil isn’t concerned with satanic influence or generation wars or piety; Samantha’s fate has no clear ties to a particular vice or societal ill, just bad luck that she needed the cash for the first month’s rent — as agreed upon with the landlady, played by none other than scream queen Dee Wallace (The Hills Have Eyes, Cujo, The Howling, Critters). The closest we get to a religious connotation is the opening title freeze frame: that apartment Sam rents in the first scene is located next to a church — significantly, the shot shows her strutting in the opposite direction, toward the camera. The satanic business is remixed alongside other quintessential ’80s-isms — babysitters, Victorian houses on the edge of town, co-eds, pizza delivery, butcher’s knives, 16mm grain, and lots of slow zooms. It’s the kind of film that is relaxed, unhurried, and confident enough to let it’s protagonist roam the large, creaky house at length — playing harpsichord, trying on Coke-bottle spectacles, talking to the fish — and then to do that sequence all over again — with dancing!

That second sequence is a marvel. The tonal flow West orchestrates is masterful. Sam’s first slow slink through the house is classic horror fare — shadowy hallways, ominous, spare piano and strings, slow pans, unexplained bumps upstairs, closed doors, attention to strange decor, potential foreshadowing at each step. The second go is just a degree away from Risky Business. Cueing up The Fixx on her chunky Walkman, Sam plays pool, spins through the kitchen, hops up the stairway, the edits and the swings and dollies of the camera matching the beat of “One Thing Leads to Another.” The tension from that initial stroll lingers, and you’d think that we’re working toward a significant scare. Instead, as danger lurks outside and inside, the music video vibe of the replay is a release, embracing the distancing effect of the ’80s-style cheesy obliviousness while letting the eerie undercurrent stay below the surface. Characters listening and bopping to dated music when they’re in mortal peril is a stock horror setup. But the way West weaves these sequences together, so fluidly, with consonant images and movements between them, is unusual and remarkable. And the punctuation? A baby sitter’s worst nightmare: a broken vase. The ritual sacrifice will have to wait a little longer.

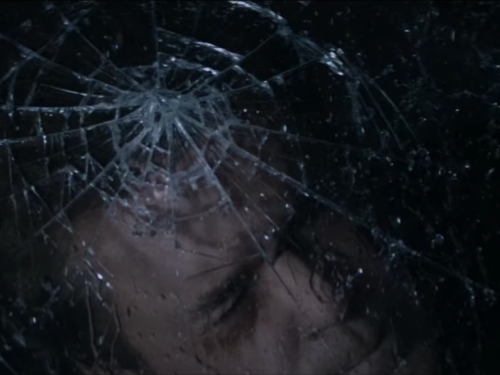

Actually, that subtle shift in style between the two house tours is something of a dry run for the gear shift of the last act. After cleaning up the porcelain and stumbling on some shady business involving missing homeowners, a red Volvo, and a whole mess of shorn black hair in the bathtub, the tension ratchets back up. This time it snaps. Drugged via pizza, Sam comes to on a pentagram; the Ulmans reemerge, cloaked like druids, and they have company, a disfigured accomplice who leads the ceremony involving a blood-filled skull and some finger-painted body art. Sam is forced to fight her way out, and the style of the film flips to match the urgency. Handheld shots and jump cuts take over, flash frames of a malevolent, gnarled face shout out The Exorcist while the climactic scenario of a demon seed is pure Rosemary’s Baby. West clearly has affection for ’80s splatter flicks and the high art of New Hollywood equally, acknowledging how one phase led to the other and how the passage of time has put them shoulder to shoulder.

The House of the Devil, by dint of its moment in time, is a hermetic, synthetic Satanic Panic fetish object. This is by no means a knock. It’s a beautiful, detailed, concise piece of fan worship that recreates with immaculate fidelity but never feels like it’s anywhere other than 2009. Compared to its peers, the other highly acclaimed horror films of this century, it’s a stylistic anomaly — deliberate, personal, textured, self-contained, and ambivalent about imbuing a larger metaphorical meaning. “I was always obsessed with the Satanic Panic of the early ’80s,” West said, close to the film’s release. “It just made sense to me. As far as the period, it wouldn’t make sense to set that kind of movie nowadays.” The naïve melody of The House of the Devil attests to that. By that logic, the time is ripe for another Satanic Panic exploitation boom. There’s plenty of widespread paranoia and reactionary opportunism to go around, and the counterculture cachet of Satanism is as high as ever. It’s a deep well of terror that’s clearly embedded in the collective unconscious, resurfacing over and over in cycles. If our current hysteria ever ebbs, there should be plenty of strange, unsettling relics for the next generation of genre cultists to cannibalize.

Find the complete October Horror 2021 series here:

Purchase The House of the Devil on Amazon

Find The House of the Devil on your preferred streaming service through JustWatch

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)