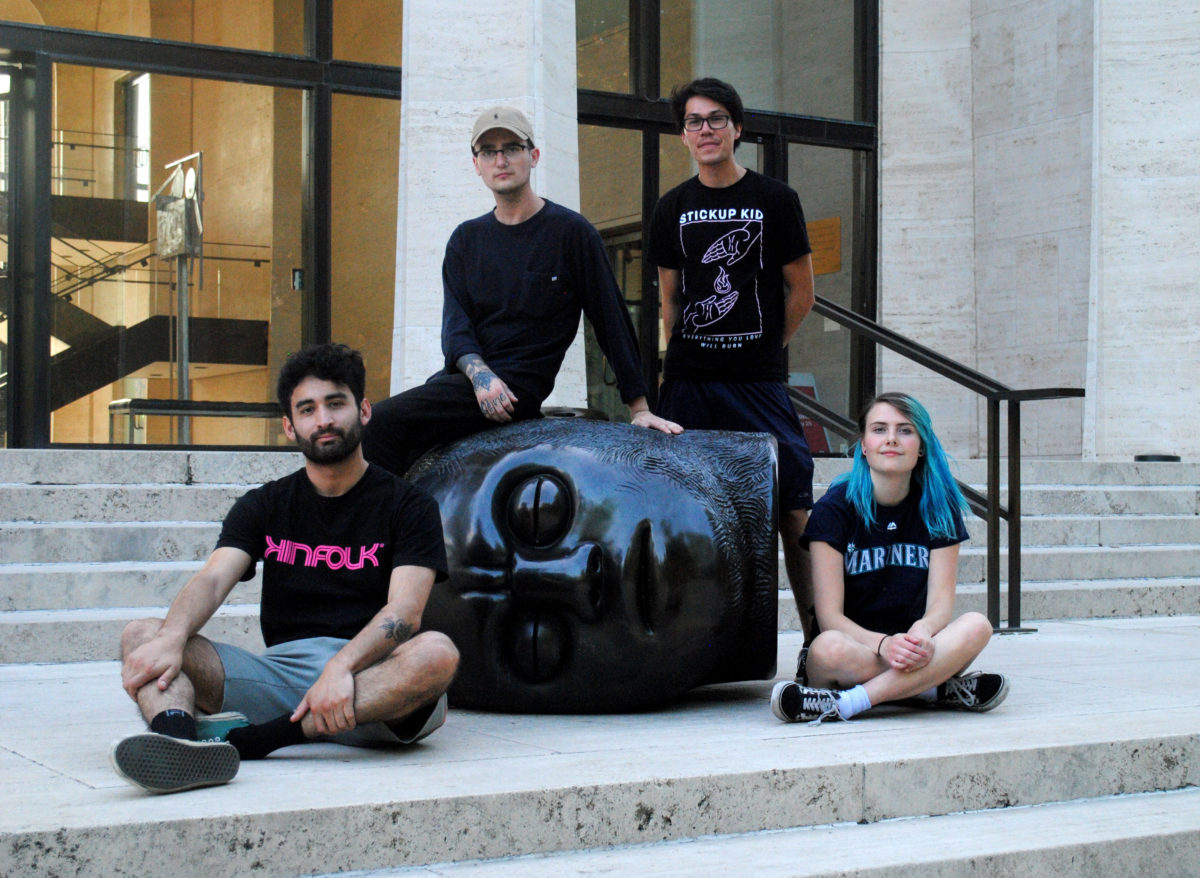

This is the third part of a series documenting Glacier Veins’ Midwest tour in May. It was written from the backseat of the band’s tour van, Connie. Check out part one here and part two here.

It was 6 a.m. and Jason Espinoza — Glacier Veins guitarist — was shotgunning a beer in the driveway.

The rest of the band was loading gear out to Connie the Van from the house of a music photographer they’d stayed with for two nights in Frankfort, Illinois.

“Today is going to be one for the books,” said Kyle Woodrow, Glacier Veins bassist, shaking his head and laughing. Woodrow and Malia Endres, vocalist and founder, had slept only a few hours after the May 25 show in Dekalb, Illinois. Espinoza and Jesse Beirwagen, drummer, hadn’t slept at all.

Woodrow offered to bear the load on a five-hour trek to Howell, Michigan, for Bled Fest that Saturday morning. “Just get in the van and I’ll do the rest,” he said.

Connie, for all her charm, isn’t a particularly comfortable vehicle. Glacier Veins spent upwards of 80 hours in the van on this tour — contorted in bizarre shapes, hugging pillows and sticking legs in the air as they tried to find a way to get some shut-eye en route to the next show. It isn’t as glamorous as the rides of 1970s rockers. There’s no mini fridge, iPhone chargers are traded around like cigarettes in prison and everyone’s stuff always seem to be everywhere, despite all attempts to organize. But for a band still finding its footing, the chance to be on the bill at Bled Fest makes the discomfort bearable.

“It definitely was the best day I never would’ve thought could happen,” said Endres.

Sleep hadn’t been much of a theme as the band criss-crossed the Midwest over the prior week. Glacier Veins hadn’t had a night off since Sunday, playing five straight shows leading up to the festival and one more the next day. After leaving the venue, some nights the band would drive hours farther to get closer to the next gig. Following a show in Fargo, North Dakota, for example, gear was loaded up and the gang drove three-and-a-half hours to Minneapolis, pulling in outside another band’s house around 1:45 a.m. But the effort was worthwhile, mitigating the trip to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the following day from eight hours down to five.

Long nights and makeshift plans are a reality for a band at this level. It’s a necessary step, one that Endres sees as similar to dropping cash on a college degree. “You need to invest something to get anything out of it,” she said. And, for all the hard mileage, touring at this level is its own reward. “I told myself when I was 18 or 19, that I’ll be happy if in my 20s I can do one tour in a van. Now I’m on my fourth.”

“I get a lot more joy loading into a basement than having multiple semi trucks full of shit that a crew of 40 has to set up for me,” added Woodrow.

Plus, Endres points out, if there’s a time to put in these tough hours, now is the chance while backaches are negligible. For a band with an average age of 23, these were fleeting discomforts. Like the bill at Denny’s, it was all part of the cost of seeking success. When Glacier Veins rolled through the gates of Bled Fest around noon on May 26, much of this was forgotten. Connie was tucked into a parking space in the band lot, and the group buzzed with excitement.

“Sleep deprivation was a thing, but I wasn’t tired because there was so much cool stuff happening,” said Woodrow. “It gave me so much more energy watching bands, watching friends. The overall good vibe of the festival was so contagious.”

Even the parking lot came with a sense of backstage exclusivity. Half the vehicles parked were large white vans stuffed with gear and luggage. Bands milled about, smoking cigarettes and calling hellos out to familiar faces. A handful of musicians that Glacier Veins had played with along the route that week were there, either on the bill or just to watch. The group pointed out later how much this became a part of the vibe of the day — there always seemed to be a band on who they knew personally, or a greeting from a friend in the crowd.

“It was like the calm before the storm. Just being able to walk around, watch some bands, talk to some people, just hang out,” said Beirwagen.

To enhance the feeling of a reunion, the festival took place inside a high school. The cafeteria, classrooms and hallway lobbies were repurposed as stages with an all-day rotating cast of musicians. Fluorescents were traded for stage lighting and lunch tables tucked away to make room for the writhing, thrashing pits in the center of the crowd. It was an appropriate evolution of the traditions of the DIY scene. En route to Bled Fest, Glacier Veins had played in a living room, coffee shops and a basement — all spaces that had been commandeered as stages — it only made sense that the next level of that would be to convert an entire public school.

Despite the pomp and circumstance of the event, despite it being on a scale that Glacier Veins had only ever played to at Warped Tour years earlier, once the band hit the stage, it was like any other show. Beirwagen adjusted his cymbals, Woodrow played with the tuning on his bass, Espinoza slapped his pedals on and off and Endres lightly strummed her blue Stratocaster as she checked the center microphone — and then they ripped it.

“The second we started playing, it was on. I felt like we all were bringing it. It flew by. To me, it seemed like one of the shorter sets of the tour,” said Woodrow.

“It was the sweatiest gig I’ve ever played,” said Beirwagen.

In retrospect, Bled Fest provided a handful of opportunities. For one, it was a shot at validation — valuable currency for a young band.

“Seeing our names with some of the headlining bands and thinking, ‘Wow, I’ve bought tickets to go see these bands and now we’re playing a festival with them,’” said Endres. “I want to work hard so we can keep growing. Maybe we’ll be headlining a festival someday.”

“I’ve always looked up to drummers, I’ve wanted dudes to come up to me after a show and talk to me about drums, I’ve wanted to be that inspiration to people,” added Beirwagen. “Being able to play Bled was one step closer to that.”

But for the band as a whole, Bled Fest, and the tour, represented a chance to expand into a region that may never have seen them otherwise. The festival allowed them to connect with a new fan base and a treasure trove of relatable musicians.

“We were able to play for and meet a bunch of people, all together in one space, from a region we haven’t really gotten to play before,” said Endres. “We hit so many birds with one stone.”

Though the band was able to pinpoint this handful of takeaways on the experience, for the most part, it hadn’t really sunk in yet. Espinoza was just riding the high.

“I don’t know how to measure the success of it, but I think just feeling good about it is good enough for me,” he said.

Glacier Veins traveled about 40 miles that night after the festival ended, to attend a house party with a few bands that were close friends by that point: Kayak Jones, Stars Hollow and Bogues.

“It kept the good vibes going way past when the festival was ended. It was just a good day with people who are passionate about music, like us,” said Endres.

Attendees mingled and mixed, as if the greater community was one massive orchestra, rather than a collection of separate smaller units, heading in different directions the following day. Each group had its own character, born from its region and personality, but all had an appreciation for the post-festival excitement.

At one point, an aerosol spray paint can flew from a hand at the side of the house and slammed hard into the rocky patio. A few members of Kayak Jones rushed after it. One looked back at a handful of surprised onlookers and explained: “It’s an old Iowa game. Throw the paint can till it explodes,” he said matter-of-factly, before chasing it down.

It was a raucous night, and an appropriate last hurrah for Glacier Veins — surrounded by musicians, cheap beer and drunken sing-alongs, whether or not the ones singing were used to holding a microphone. These shenanigans were as much a reward of the tour as exposure. Wild nights and artistic collaboration go hand-in-hand.

“Networking is the business side of it, but you’re really just connecting with people and making those relationships,” said Endres. “Maybe we’re going to tour with one of those bands we became friends with, maybe we’ll help them out with a show in Portland or stay at their house somewhere in the United States.”

It was a grueling 2000-mile-plus ride back to Portland, spread over three days, crossing much of the same territory the band had covered on the way to the Midwest a week earlier. “This shit, it’s like a never-ending screensaver. I don’t mind, I could stare at it for hours,” said Woodrow. “I have been staring at it for hours,” Beirwagen snapped.

Despite the long drive to absorb it all, and for all the build of eight shows in nine days, the tour seemed to be over in an instant. A dozen states, countless new faces and enough Mountain Dew to kill a horse were a memory. But for the band, it was motivation to keep working.

“Tour, tour, tour, tour tour tour and more tour. I feel like we’ve been on the rise — getting out there as much as possible, racking our brains to get dates and do the thing,” said Woodrow. “You get out what you put in. It doesn’t happen overnight.”

“It’s like this trifecta — we get to make friends, we get to see places and we get to play music, which is my favorite thing to do,” said Endres.

“We know what we’re all capable of, so it’s kind of exciting to see what else we can do,” added Espinoza. “I don’t see any reason to slow down. This tour felt a lot more comfortable than the first one. So the third one, the fourth one, it’ll just be all that much better. We just have to keep doing it, not let up on the gas.”

When the van pulled into Portland after a 25-hour non-stop drive, the members of Glacier Veins spilled out like a prank can filled with snakes. There were bags under every pair of eyes and gear fell haphazardly onto the lawn as everyone sorted through the mess Connie had become.

There’s often a grand takeaway from time with a band. There’s a sentiment that says ‘This is who we are, this is where we’re going.’ Hard as I tried in nearly two weeks with Glacier Veins, I couldn’t extract a greater purpose or a mission statement. It wasn’t that the band was directionless, but that its purpose — through line-up changes and car trouble — was simple, stated every night and in every interview: get four talented, like-minded people together and play music as often and as loudly as they can, and keep making it better.

For this group of scrappy young musicians, it felt like that was enough.

With the sun rising in NE Portland just after 6 a.m., Espinoza grabbed his last bag out from under a seat and pulled his hood over his head.

“I’m gonna go home and play guitar,” he said.

Glacier Veins will be back on tour in June in California with a June 23 date at Mountain View Warped Tour and a June 26 date in Los Angeles. The band plans to release a full-length album in 2019.

Watch for future installments of On the Bus coming soon, and follow Cooper and Split Tooth Media on Twitter for more

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)