Often glossed over as a minor project in Stills’ long career, his two albums with Manassas demonstrate how he thrives in ensemble settings

Stephen Stills is an elusive figure in the back half of 20th century rock history. Part of perhaps the most critically acclaimed supergroup of all time and the mind responsible for the most emblematic protest song of the ’60s, Stills still flies under the radar. He had a lengthy solo career with several hits to show for it, yet he remains one of the most unsung but highly influential rock figures of the era. Perhaps the reason for this lies in what is his greatest strength: Stills is a born collaborator, and his best work tends to come in close collaborative environments. There is no better example of this than his two Manassas albums from the early ’70s.

Before the formation of Manassas in 1972, Stills already had a history of collaborative efforts. Most obviously, the 1969 eponymous debut album of Crosby, Stills & Nash and 1970’s Déjà Vu from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young were a strong endorsement of the supergroup format. Not only could they come together in unbelievably unified harmony, but each could explore their own ideas and alternate taking the helm with expert backing that brought their visions to fruition with more dimension. Stills would have secured his legacy with this alone, even if he never played another note outside of these records. But he did — and we are all better off for it. Before CSN and CSNY, however, Stills took part in an album, the success of which opened the floodgates for the supergroup concept, and paved the way for future Stills efforts like CSN, CSNY, and Manassas.

In May 1968, Al Kooper, fresh off leaving Blood, Sweat & Tears, called his colleague from Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited sessions, Mike Bloomfield, who was about to leave his band The Electric Flag, to see if he wanted to jam. Bloomfield agreed, and Kooper booked two days of studio time, hiring a few other session musicians. After the first day of recording, Bloomfield, a noted insomniac, returned home to San Francisco saying he had not been able to sleep the night before. Hurriedly, Kooper turned to another great guitarist in the area, Stephen Stills, who was in the midst of leaving Buffalo Springfield. Stills sits in for Bloomfield on the second half of the Super Session album, and already he shines in a collaborative environment like this. Listening to him play on an 11-minute version of Donovan’s “Season of the Witch” or a cover of Bob Dylan’s “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” it is not surprising that he would go on to thrive in group settings. He strikes a perfect blend of serving it up to Kooper and still getting some great licks in there that only make the experience richer.

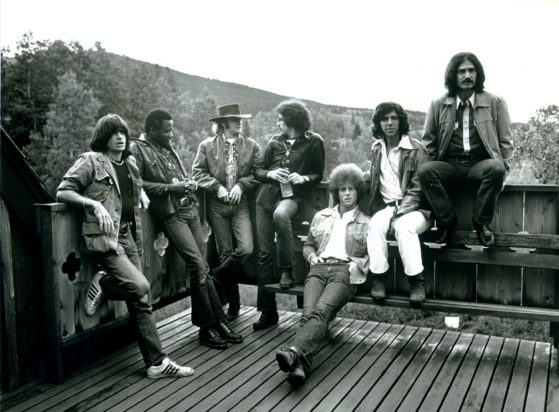

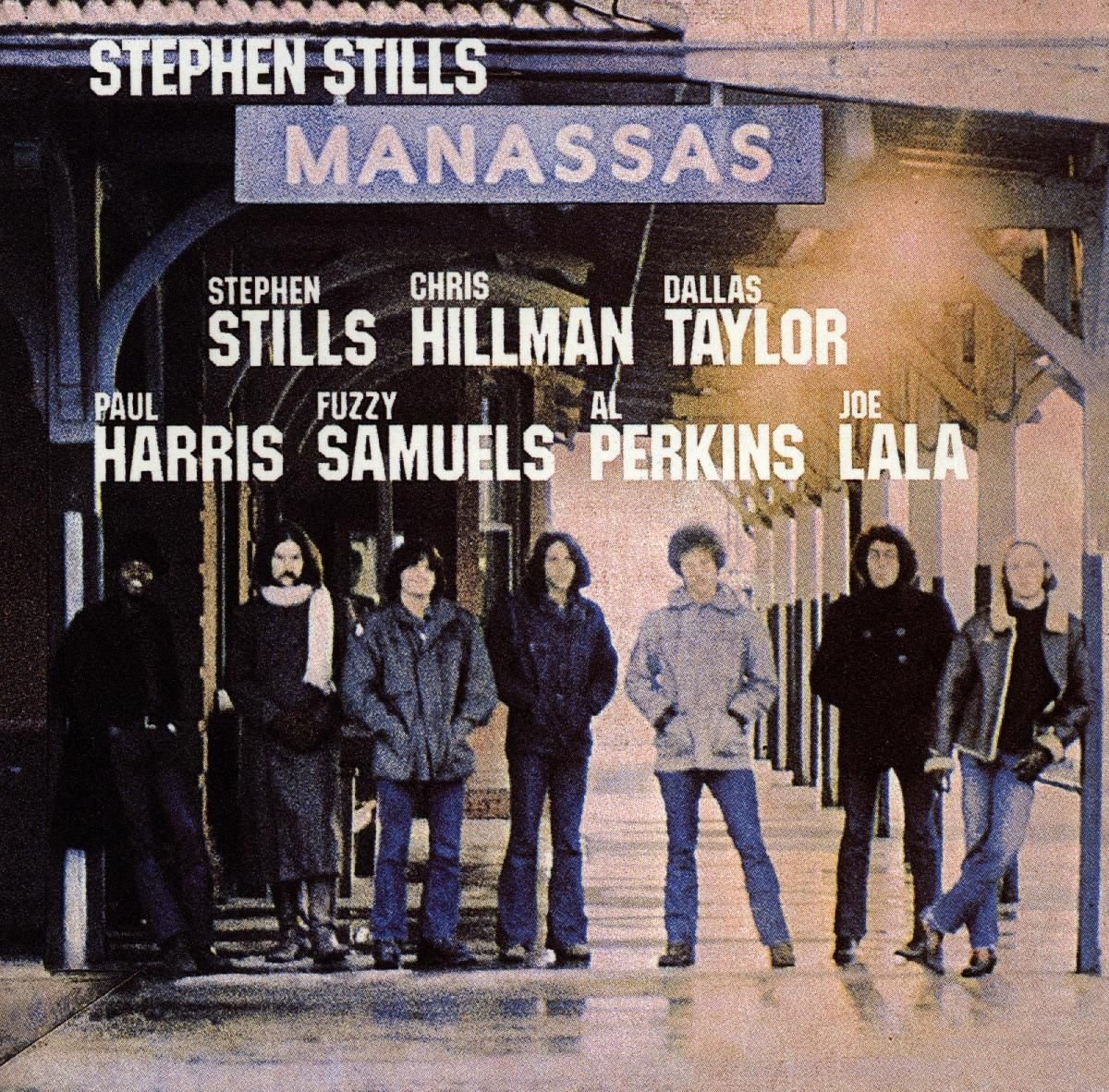

Manassas came about because of a chance encounter. Touring to support his second solo album, Stephen Stills 2, Stills crossed paths with Chris Hillman, singer and multi-instrumentalist in The Flying Burrito Brothers, when their tour dates lined up in Cleveland. Stills’ second solo album, as the first of his to come out after the messy 1970 breakup of CSNY, was not well-received, and Hillman was not as invested in the Burrito Brothers as he once was following numerous personnel changes and financial troubles. Sensing a kindred spirit in a similar situation, Stills called Hillman up and invited him and two of his fellow Burritos, guitarist Al Perkins and fiddler Byron Berline, to Criteria Studios in Miami for a jam session. Stills also invited a few members of his touring band, including drummer Dallas Taylor, bassist Calvin “Fuzzy” Samuels, keyboardist Paul Harris, and vocalist/percussionist Joe Lala. This lineup would become Manassas.

The group got on exceedingly well and within a few weeks had enough quality material for a double LP, its 1972 self-titled release. Manassas is a wonder of a record and a remarkable testament to the collaborative Super Session-esque format. Split into four thematic sections over the four sides of the two LPs, Manassas opens its first section, The Raven, with “Song of Love.” From the start, this album has a different feeling than Stills’ first two solo albums, and even the similarly situated CSN and CSNY albums. It sounds fuller, and there is a very dynamic quality to it, as if it lives and breathes on its own. As the first few songs play through, the band explores an incredible amount of different influences and flourishes. It is so clearly a product of collaboration and diverse perspectives that it almost puts the listener at the center of it, leaving them eager to hear where the group goes next, what new harmony or motif they might pull in and explore.

The medley of “Rock and Roll Crazies/Cuban Bluegrass” is a great example. A product of co-writing between Stills, Taylor, and Lala, it blends rock, bluegrass, and Latin styles into one seamless groove. Even down to the vocals, the collaboration in the first section is strong. Stills and Hillman duet on “Both of Us (Bound to Lose),” a co-write between the two, and it is a perfect blend of the styles they both bring to the table. They push each other into some of the best vocal performances of their careers, something that could only exist through this collaboration.

The second section is The Wilderness. It starts in a similar vein to the first, with the driving bluegrass of “Fallen Eagle.” But then there is a tonal shift into songs like “Colorado” and “So Begins the Task.” They see Stills take the lead, but they transcend his leadership — these songs are more complex, more layered. It forces Stills to push himself, and it, in turn, makes them all better. There are soaring harmonies, and numerous flourishes that could only come with a jam session like this, evident in the gorgeous collective unison of “Jesus Gave Love Away for Free.” The blending of influences is masterful in the section’s final song, “Don’t Look At My Shadow,” a rollicking country-infused tune where Stills owns the twang as if he were a long-lost Burrito Brother. This song shows Hillman pulling something new out of Stills, the beauty of this collaboration.

Related: Harry Nilsson’s Aerial Ballet Is An Under-Appreciated Masterpiece by Craig Wright

This group creation develops nuance in the second section, and it maintains this as it transitions into the third, appropriately titled Consider. It starts slower in tracks like “Johnny’s Garden,” which has a similar dynamic to the earlier songs where the Manassas members are pushing one another, but it plays more subtly and less explosively here. Stills and Hillman then come back together for another duet, the Burrito-esque “Bound to Fall.” As they trade verses, the intensity rises, and the rest of Manassas rises to meet them. “How Far” and “Move Around” really lean into this, and by the last of this section, “The Love Gangster,” Manassas is bursting at the seams with the energy that has been building up in their interplay through the past three sections.

Manassas’s final section, Rock & Roll Is Here to Stay, sees the explosion of this energy with rockers like “What to Do” and “Right Now,” which comments on CSNY and Stills’s relationship with Graham Nash in particular. It ends with “Blues Man,” presented in tribute to Jimi Hendrix, Duane Allman, and Al Wilson. However, the shining moment of the fourth section, and perhaps the entire album, is “The Treasure.” The eight-minute jam twists and turns through different melodies and tones. Each member takes an opportunity to contribute as the track keeps building momentum and reaching new highs at every note, flourish, and chord.

The first Manassas album was Stills’s critical comeback. The group received considerable praise, but lots of individual accolades were for Stills and Hillman. In perhaps the most emblematic review to come in the wake of Manassas, Andrew Weiner writing for Creem said, “Stills, perhaps the most maligned superstar in recent rock history, has finally — and against all the odds — got it on. And Stills has written too many good songs here even to try [to] count them.” The album was certified gold just a month after its release, but it was pulled as soon as it hit that milestone. Stills attributed that to Atlantic Records head Ahmet Ertegun wanting to pull him back into the money-making machine that was Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

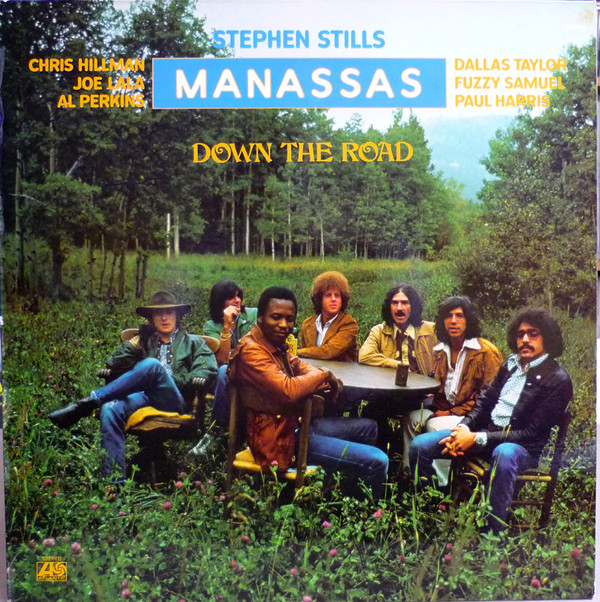

Manassas regrouped in Criteria Studios in early 1973, ready to record a second album. They were all at different points in their lives. Stills had recently married French singer Veronique Sanson. Hillman had reunited with The Byrds for a reunion tour and was being courted by Asylum Records to form a new supergroup with J.D. Souther and Richie Furay, ironically also a Buffalo Springfield alumni like Stills. Arguments and drug use ravaged the proceedings, and Stills maintained a rigid round-the-clock studio schedule that caused tensions to rise and him to lose considerable money paying for each musician. Against this backdrop, their second record would prove to be their last; however, the album does not let on just how much dysfunction was taking place behind the scenes.

Down the Road (1973) is half the length of Manassas, yet it packs an equally compelling punch. If the spirit of collaboration pervaded the first album, it is abundantly manifested here. Everyone plays a full role, with Stills gladly taking even more of a backseat, serving it up with searing guitar even when he is not at the mic. In many ways, Manassas feels like the journey to the destination of Down the Road. Their first album was a lengthy exploration, the second is tighter with a more unified vision.

The album starts strong with “Isn’t It About Time” and immediately Stills hands off the mic to Hillman, who gives a tremendous performance on “Lies.” The momentum of the front half of this album culminates in ”Pensamiento.” While Stills takes the lead on the Spanish vocals of this Latin-infused rocker, everyone in Manassas is at their best. You can hear them pushing each other, feeding off of that energy as they reach the climax of the song. It is a shining moment in Stills’s discography, brought about purely through the ensemble environment.

After this, Manassas slows down for “So Many Times.” The song features gorgeous harmonies, showing just how in-tune with one another the band members are at this point. They take their harmonies to the next level, singing in unison on the pure country rocker “Do You Remember the Americans.” Stills is no stranger to harmonies at this point in his career, but they feel distinct from those he crafted with Crosby, Nash, and Young. While the CSNY harmonies are unified, their separate voices are still distinct. It is a group of individuals first, and the harmonies reflect that. However, the Manassas harmonies do not have this same separation of voices. It is much more challenging to pick any one member out over another; there is a true oneness and unity to the harmonies. It feels more like a collective whole, one living and breathing being than a group of individuals.

Down the Road did not enjoy nearly the same level of popularity or critical praise as its predecessor, and Manassas broke up. The two albums they made are easy to gloss over as a brief interlude in the middle of Stills’ lengthy, acclaimed career. But few of his projects articulate more clearly and richly that Stills was not only one of the best guitarists and lyricists of his era, but also that he was so willing to serve it up to the other musicians he surrounded himself with — and he’d not only just serve it up, he’d relish in it. His best work comes when he is with other similarly driven, innovative musicians — it pushes him to his best and focuses him on a single vision while simultaneously exposing him to new, infinite musical horizons. There is no better single encapsulation of this than the two Manassas albums.

However, in discussing Stills’s collaborative efforts, one with any general knowledge of his work and relationships might ask how one of the most notoriously difficult musicians of the era could be such an effective collaborator. He worked Manassas to the bone, one of the driving factors in their eventual breakup. He had a reputation for being fully aware of just how talented he was, with Rolling Stone passing him up for their May 11, 1972 cover due to the critics’ dislike of his arrogance.

While being one of the most esteemed and successful supergroups of all time, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s legacy is almost overshadowed by their lengthy and often public infighting. Of course, Manassas met the same fate. The stark contrast between his proclivity for collaborative efforts and his inability to maintain them is a startling contradiction and one that feels almost impossible to reconcile, almost as if they were two different people. Yet, the music he leaves behind with those partnerships is incredible, a true testament to collaborative efforts that had a few shining moments of unity but on the whole were quite contentious.

Perhaps it is not a question of reconciling these two sides of Stephen Stills. Instead, maybe his career is a portrait of a man so driven by his own ambition and ability that he was overcome by it. Despite his ego, it was not really about him in his mind. It was all about the music. While he frequently believed he was superior in that ability, it never prevented him from working with others in pursuit of that end vision. The music and the megalomania can co-exist — it is just not hospitable soil for an enduring collaborative model. He would quickly burn himself and others out, but it made those moments of pure collaboration, like the Manassas albums, even better. His ego drove him to constantly pursue new heights, and he almost always reached them. He believed he was the best and he would prove it, which pushed him to surround himself with the best talent he could find to do it. That is maybe what makes him such a successful collaborator, albeit never a long-lived one. In short, Stills is a fascinating character study, known for some of the greatest collaborative efforts of all time, yet also notorious for his difficulty maintaining those relationships. This contradiction only makes the study of Stills as a collaborator and the efforts that came of those partnerships all the more fascinating. Thankfully, with the timelessness of the work he created in those brief shining moments of harmony and unity, it is a consideration that can continue for years to come.

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Breanna on Twitter

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)