October Horror 2022 kicks off with a movie overflowing with homemade monsters

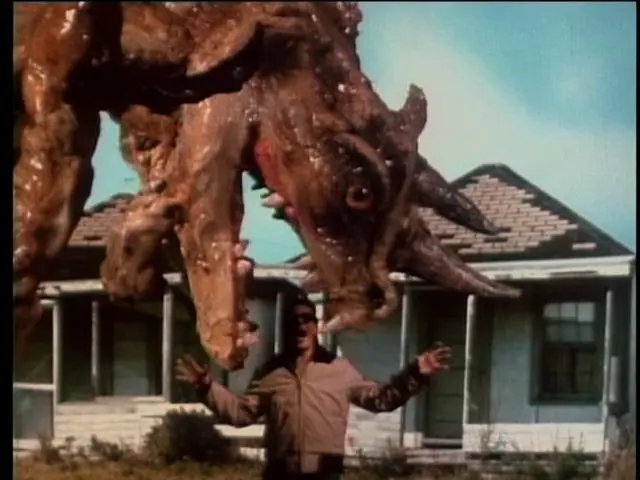

Winterbeast is the scrappy stop-motion monster extravaganza you’ve probably always desired but never knew existed. It somehow stands as evidence of both an abandoned live-action horror film shoot and what can happen when an animator, in an effort to salvage years of work, takes a Ray Harryhausen obsession as far as their creativity can go. The film is about forest rangers investigating several disappearances in the woods of New England. There’s a sinister lodge owner, and a plot involving that old outdated trope of an ancient Indian burial ground. But the story doesn’t matter much. Winterbeast is all about its set pieces. Throughout the course of the movie we encounter an alien, a dinosaur, a giant chicken, a moleman (at least, I think it’s a moleman), a mummy, various skeletons, a tree creature, and, of course, the Winterbeast, a fire-flinging warlock. Winterbeast is the type of movie that could only have been made by amateurs, for it is so clearly the product of young artists working with the sole intention of making something they themselves would want to watch — lack of funds, reputations, and all else be damned!

The film is messy and scatterbrained in the best possible ways. As it stands, the narrative feels more like the remnants of a lost drive-in flick buried under a more extravagant creature feature. This will frustrate some viewers. Anyone looking for something conventional and neatly plotted, be warned that this movie will most likely drive you nuts. But Winterbeast lives and thrives on one sage piece of wisdom that more low-budget horror films desperately need to adopt: When in doubt, add another monster.

Shot over the course of nearly half a decade, the production of Winterbeast was mounted by Mark Frizzell and Christopher Thies. Frizzell, a stop-motion animator, was working mostly in commercials at the time while employed at Boston’s Olive Jar Animation Studios. Olive Jar was perhaps most famous for their spots on MTV and Nickelodeon. Thies was a young, aspiring filmmaker with a short horror film under his belt. He showed it to Frizzell who saw promise in it and asked if Thies had anything new in the works. Thies mentioned “Winterbeast,” which at the time was little more than a collection of notes and a title. His ideas resembled a monster movie that Frizzell was developing, so they decided to work together. Thies’ notes were organized into script form, and in 1985 they began work on the film.

From the beginning, Winterbeast was conceived as a passion project. Budgets were humble. Casting was simple: for the most part, if you showed up, you got the part. The production was scheduled around its creators’ paying jobs. Frizzell, working as the producer and editor, did a great deal of work on the film’s effects at Olive Jar. He would arrive early in the morning to work on Winterbeast before clocking in to produce commercial work for clients. A good amount of the live-action footage was shot on location around Massachusetts, at landmarks such as a Native American-themed tourist stop on Route Two and on the streets of Concord. Other locations, which many initial viewers believed to be the actual homes of the filmmakers, were hand-constructed sets that stayed up in a rented studio space for years. Regarding the materials used to construct these sets, which gave the film its lived-in feel, an archival commentary track with members of the crew confirms that “everything came out of the trash.”

There was a lot of learning taking place throughout the course of the shoot. In interviews included on the recent Blu-ray release of the film, Frizzell mentions specifically that the production fell prey to many “distractions,” mostly involving money and potentials for distribution. When investors came calling, the production would stop in order for trailers or teasers to be cut by the naive crew, in hopes that their footage could draw more substantial funding. Somewhere in 1989, after nearly half a decade of work, actors and crew were worn down. Winterbeast fizzled out. Frizzell moved west for work, taking the incomplete film with him. He eventually decided to pick it up again and patch the pieces together into a finished film, which was eventually released on video in 1992.

Now, in the realm of low-budget horror films, this type of situation is rarely a positive thing. Usually, it involves a money-minded producer taking the film away and padding it out with sex scenes or inexperienced first-time filmmakers adding as much footage as they can find in order to scrape a sellable 90-minute product together. How many potentially great cheapo monster movies are ruined by the excessive use of stock landscape shots or repeating the same moon-rising-through-the-trees image over and over to fill time?

Frizzell took another approach: When the production first appeared to be falling apart, he decided to fill in the gaps from scenes and shots that either weren’t filmed or had to be cut due to various setbacks by adding new monsters. When he returned to Winterbeast after moving west, there was no deadline for the film so Frizzell and his colleagues had time to transform it into a ragged showcase of monster effects. For instance, when a scene involving the Winterbeast was unable to be shot for the film’s first act, instead of padding out the runtime with scenes explaining what couldn’t be shown, a completely unrelated claymation tree monster was created to fill the void. Some monsters were repurposed out of pre-existing materials from other projects the crew had worked on, including a mole monster whose first life was as an aardvark on Nickelodeon. With this freedom, the film conjures as many creatures and spirits as its creators could muster to populate the haunted forest. If Winterbeast is guilty of anything, it’s of having too many monsters — but who would ever consider that a bad thing?

Well, Winterbeast was initially panned. The less-than-stellar acting and incomprehensible plot caused viewers to believe it was a mess. But the film gradually gained a cult following on video. More receptive viewers discovered it who appreciated it on its own terms as a strange and modestly brilliant display of stop-motion work. In a sense, the closest comparison point to Winterbeast would be something like Spookies (1986), another creature feature that ran into production troubles — much more severe troubles though that involved lawsuits and feuds over the final version — and developed a cult following. Set in a haunted house, Spookies fills every room with different monsters: A spider woman, grim reapers, even a gang of fart monsters. But where the released version of Spookies utilizes an episodic, almost video game-like structure where each monster feels like a boss to be faced by the characters, Winterbeast goes further off the narrative rails and stays the rough course rather than trying to right itself. It is far less concerned with weaving its monster encounters into the story elements. Winterbeast begins in a dream sequence and cuts bizarrely between events that seem to be happening outside of the dream to characters who are never properly introduced and are never seen again. The opening sequence is completely disorienting but delivers more monster carnage in a matter of minutes than most films do in their full runtimes.

The non-monster scenes also have their moments. They frequently feature actors performing in scenes in which different shots were clearly staged months or years apart from each other. This makes the experience of watching Winterbeast almost more about watching people in the process of acting before the camera than it is about the story that is actually being acted out. For better rather than worse, it is hard to invest oneself in the narrative because the film is so off kilter. Due to the extended production and the long breaks between shoots, mustaches change shapes and sizes from one shot to the next; haircuts rarely match up; guns are fired every which way except the direction that standard editing logic would deem correct. In one particularly memorable scene, a misunderstanding of how to frame conversations by the crew caused the lead ranger to appear as if he is fluctuating in height while talking with a shorter coworker. Notions of blocking for the camera were also foreign to many of the actors. This caused some trouble for the camera operators. Due to the low budget, there was pressure to keep many scenes to single master shots to save money on film. Therefore, when actors would start wandering out of their designated areas, you can catch instances where the camera operator is having to decide in the moment whether to follow the roaming actor or stick to the initial setup and hope they find their way back into the frame. These are obviously issues that arose from lack of experience. But when taken together with the strange inconsistencies in continuity, the film creates an unintended but endearing distancing effect throughout these attempts at filming the more traditional dramatic scenes.

Related: Malatesta’s Carnival Of Blood (1973): Owning The Artifice by Brett Wright

The film is also genuinely disturbing for about four minutes. The scene in question involves no monsters. It features the evil lodge owner, Mr. Sheldon, played by an actor named Bob Harlow. For most of the film, Sheldon functions along the same lines as the mayor in Jaws. As the death toll rises around his property at the peak of vacation season, he battles with the authorities to allow his business to stay open regardless of the danger. Harlow’s loud and sassy performance makes Sheldon a highlight of the film. He chews through each of his scenes with relish and then spits them right back out so that he can move on to his next flannel-clad tirade. It’s incredibly enjoyable watching the other less exuberant actors try to hold their ground in scenes with him.

Towards the end of the film though, we are treated to Winterbeast’s most bizarre moment when Sheldon retreats to his office late at night. The lodge owner puts on a children’s record (“Oh Dear, What Can the Matter Be”) that is so sweet and cute it’s terrifying and dances around to it in a demonic clown mask. Sheldon’s office is fashioned with shrunken heads, decomposing corpses, and cheap Halloween decorations, all of which he incorporates into his private performance. And of course, the Ed Gein-esque masquerade ends in an extremely odd manner due to troubles on the set: While shooting, Harlow couldn’t remember his lines and the film supply was running dangerously low. With no time for retakes, the filmmakers decided to work with what they were able to get. They refashioned the scene so that it ends with Sheldon bursting into flames and magically disappearing. It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, but, like the rest of Winterbeast, his exit will stick in your brain. For all of its flaws, what makes Winterbeast most admirable when compared to other low-budget monster films, is that it doesn’t succumb to the usual compromises made by so many productions faced with similar setbacks. Winterbeast refuses to fall back on bland conventions and takes the strangest route at nearly every turn.

Winterbeast is available on Blu-ray as part of the Homegrown Horror: Volume One boxset from Vinegar Syndrome or Amazon

Stream Winterbeast on Shudder and Shudder’s Amazon Channel

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)

Find the complete October Horror 2022 series here: