Synopses don’t do Brandon Colvin’s work justice. A budding filmmaker indulges his voyeuristic tendencies, an academic returns to his hometown, a mysterious group of women enter three men’s lives — Frames (2012), Sabbatical (2014) and A Dim Valley (2019) sound familiar on paper. Their premises belie a formal rigor, offbeat humor and emotional specificity that’s anything but. Colvin’s trio of features have seen the professor and programmer develop his own cinematic grammar and build a fruitful partnership with veteran actor Robert Longstreet.

On Sunday, May 31, A Dim Valley will screen as part of the Ashland Independent Film Festival. In March, Brandon and I spoke about the film and its predecessors. Other topics of discussion included Hayao Miyazaki’s dreamscapes, self-critique and the myth of prestige TV. Read the conversation below.

Split Tooth Media: You’re one of very few filmmakers I’ve encountered on Letterboxd and you’re the only one I’ve seen who rates their own films. Could you tell me more about that impulse?

Brandon Colvin: Usually when I’m rating them it’s really about whether or not I did what I wanted to do. I think I keep getting closer and closer. With more experience, I feel like I know more about managing the whole process and setting things up for success, so the ratings keep going up and up. I’m not sure if they’ll go down eventually, but I feel I’m getting more and more to where I’m in command of the process. That’s why my estimation of the films keeps going up.

Related: Michael Glover Smith: The Split Tooth Interview

You rated your first film, Frames, 3.5 stars and gave your follow-up, Sabbatical, a 4.5 rating. Could you tell me a little bit about how these compare to what you set out to do?

With Frames, there was a lot about basic filmmaking that I just didn’t know. I’d never been on a set in my life. I never took a production class. I was trusting a lot of people to manage things without the vocabulary to actually communicate with them. So, I couldn’t really comment on or make suggestions about a lot of things. I’m torn because part of me is glad it turned out that way. There’s a lot of weirdness to the movie that might not otherwise be there.

So much of movie making is trying to make everything perfect. By the time you’re done with post-production, you can still only think about all the things you’d do differently. That’s very much me with my movies. I never watch them after they’re done. With Sabbatical, there were some ideas I should’ve tweaked. It’s a pretty oblique film in a lot of ways and I think there are a few ideas I might adjust a bit if I had another shot.

SABBATICAL Trailer – A FILM BY BRANDON COLVIN from Tony Oswald on Vimeo.

Your latest film A Dim Valley gets five stars. It’s similar to its predecessor in the sense that Robert Longstreet plays an academic. Otherwise, it struck me as a definite departure from your previous work. Do you see it that way?

Yeah. I think one of the reasons for that is that all the films I’ve made so far are really responses to stuff that’s going on with me at the time, the things I’m thinking about and feeling. So, as much as they have similarities, they’re very different in their emotional palette. Sabbatical was a really dark time in my family and my life, while A Dim Valley is about embracing new aspects of myself and my work. There are things I was working out — personally and stylistically — while making those first two films that I don’t think about anymore.

Making A Dim Valley felt more instinctual. Over two movies, I think I’ve learned how to instinctually do the things that I was thinking hard about on Frames and Sabbatical. It was actually a harder script to write because, for a while, I wasn’t allowing myself to be as creatively free as I needed to be. The breakthrough with A Dim Valley was getting to a point where I was just doing everything I wanted to. Since then, scripts have been coming fast. I’ve got three more feature scripts at or near completion that are all reaching toward dreamy, unusual things and I think that’s because of the breakthrough of A Dim Valley.

Like Sabbatical and Frames, A Dim Valley goes to some dark places. In general, though, it’s a much funnier, sexier, even more hopeful film than its predecessors. Were there changes in your life or work that made it easier to explore this new territory?

It came out of a couple things. Sabbatical — even if it is a pretty dour movie — has a few formalist jokes and things we would laugh about.

Like the Hot Pocket?

Right. We had a lot of those little things that we’d joke about on set. One day we just started talking about doing something more overtly comedic. That became the challenge. I had it in my head for a while that it’d be some kind of Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati comedy and I started to get really dissatisfied. It felt too much like an exercise. I was collecting ideas, but they didn’t really go anywhere.

Around this same time Kim Davis was the clerk for my home county in Kentucky. She was the woman who became famous for refusing to sign same-sex marriage licenses. It was a huge national thing. Mike Huckabee and all these dipshits came to my hometown. It was really frustrating and made me really sad about where I live. It’s such a beautiful place with these people who are just beacons of oppression and a spirituality that feels very destructive. That found its way into the script. I kind of said, as a mission for myself, that I not only wanted the movie to be funny, but I wanted it to reject all of that stuff. I wanted to create a new cosmological order that would welcome people who’d been shunned and make something where some kind of deus ex machina could correct all the painfulness of that whole thing.

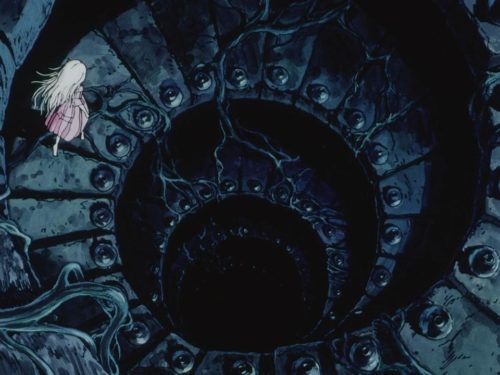

Another big thing at the time was watching all of the [Hayao] Miyazaki movies for the first time and being so emotionally devastated by how beautiful his alternative worlds were. I wanted to make something like that, something that had some kind of hope or spiritual benevolence. So, it wasn’t so much me feeling more hopeful as it was having Miyazaki as a model. In many ways I think he’s a very pessimistic person, but he has a yearning for hopefulness that comes across in his films.

I’ve only seen about half of Miyazaki’s films and I think my favorite is Porco Rosso. That’s probably his most “terrestrial” film; Porco himself is the only really fantastical element. I was really floored by that scene of him being almost cast out of heaven.

That’s my favorite one, too. And I think there’s a lot of Porco in Robert’s character.

The subject of spirituality brings up Letterboxd again. In the comments section of a user review, you suggested that Sabbatical is a film about spirituality coming out of “hibernation.” For all the differences between the films, I think there’s a sense of reawakened spirituality in both Sabbatical and A Dim Valley — particularly with respect to Robert’s characters. Could you speak to the “spirituality” in the new film? To me, it seemed not just reawakened but maybe taking form (or a certain form) for the first time.

Sabbatical is definitely about someone who has avoided a lot of things in their life and that avoidance has exacerbated their problems. It ends at a point where the character has to make a decision about how he’s going to move forward with his life — in a spiritual and existential way. What does he do at the end of that conversation? How does he behave? And part of why it’s left open is because I still didn’t know.

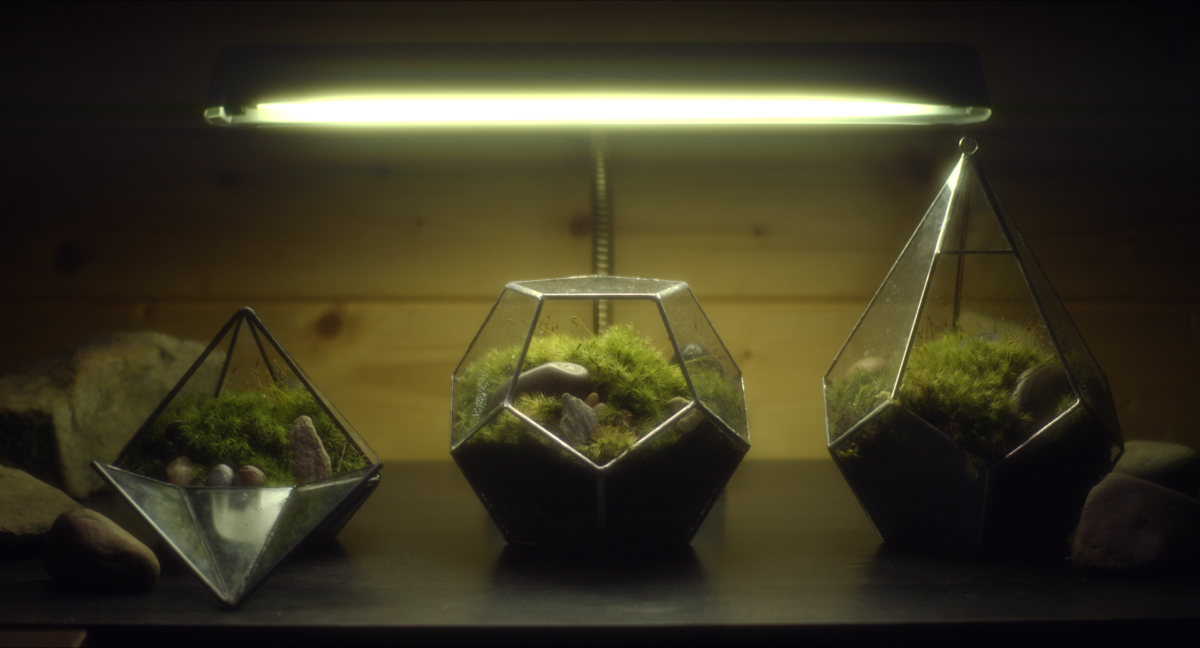

For A Dim Valley it’s less about choice and more about revelation. Having something abstract take form is another way of saying it becomes visible. I think that’s what happens in the film. These abstract, benevolent, mystical forces become visible and real and the characters can engage with them. And that’s its own kind of miracle.

The beings are summoned by Clarence in a way that’s accidental. It’s like Jimmy Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life. When he’s up on the bridge, whatever he’s doing there strikes a cord that vibrates out a call to the angel. I think there’s a sense that Clarence’s pain calls out to the beings. More than a spiritual reawakening, I see it as a force of mercy and healing that they’re encountering. It’s been a long time since he has felt like this and seeing his transformation brings about revelations for the other characters as well.

You’ve discussed the influence of painters on some of your early work. In particular, I believe you said Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper informed Sabbatical. What were some of your visual touchpoints for A Dim Valley? Is it too simplistic to assume you were calling on classic nymphs and bathers?

They definitely play into it. There are a ton of Classical Western archetypes that are informing the look, including Maxfield Parrish-type stuff. When I’m finding influences for a film, it’s really about creating a common language to communicate. It was hard for me to explain the palette and the compositions I was looking for on Sabbatical without the paintings.

For A Dim Valley, the main thing in my head was that it should feel warm and fuzzy in a relaxing way. It was definitely easier to explain what I was looking for. Films played a bigger role than paintings: Picnic at Hanging Rock, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, and other things that have this kind of smeary warmth to them. Walerian Borowczyk, he made bizarre, sexy eurotrash films like The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne. That was something I used as a reference for sure.

Where does a movie begin for you, or where has it tended to begin? Do you find yourself thinking of images, characters, events?

It’s usually images that are charged with feelings. The writing process is about trying to understand what is charging those images and why. These images stick around for a reason. There’s something that makes them a little heavier. Stuff starts to get really good when a charged image or fragment of an interaction starts to pull other things around it. Other stuff that was floating in your mind starts to orbit that thing.

Once I get enough of those charged moments and feelings, I start to connect them. Mostly, I’m just asking questions. How could these things make sense together? What’s this feeling? How can I push it in an interesting direction? Usually the characters and the direction of the plot come out of that process. Everything starts to interact and multiply.

In addition to directing films, you’re also a scholar of performance. I’m particularly interested in something you said about television performances on an episode of The Cinephiliacs. You describe TV acting as “featuring the most obvious, telegraphed form of emotion.” In the time since that conversation, streaming has blurred the lines between TV and film. How have your thoughts evolved in that time? Do you think more films are dealing in that kind of performance because they presuppose a distracted audience?

I think it’s hard to generalize because a lot of films are made with the assumption that you’ve got a distracted audience. Any blockbuster, big budget thing operates more or less that way. But there is still a fundamental distinction between film and TV that has to do with breaking the spell. When you watch a movie, the idea is that you’re consuming it in a single sitting. If you can get somebody locked into the movie, then the performances can take them to places that are pretty emotionally subtle. You can get into things that aren’t just plot-centric because you’ve engaged them. It’s not that television can’t do that — it just doesn’t.

On television, you have things broken up and that spell gets broken all the time. You can binge something on Netflix, but you’re still seeing credits and all that stuff. There’s also TV’s need to justify its extra running time with more plot incidents and characters. It leaves shows with a lot of juggling that puts pressure on the actors. They’ve constantly got to dump info on the viewer and it makes the acting so functional. It never gets to the point where it can be really nuanced and subtle because everything is purpose-built for narrative functionality.

TV sucks. Maybe that’s a controversial take, but I think almost any movie is better than any TV.

It’s not a controversial take for me. I think TV gets worse and worse the more we hear about how good it is. The question of quantity versus quality brings to mind an exchange from early in A Dim Valley. The students have been out collecting samples and they come back with just one. Clarence isn’t pleased and says something like, “this is about quantity here.” It made me think of a hack director or a movie franchise that’s interested in churning out a product. Do you think some of the character’s malaise has to do with feeling disconnected from his “art?” Do you see his studies as at all like an artistic practice?

Possibly, but I wasn’t explicitly thinking about art. I think it’s more of science as a form of spiritual practice. His relationship with the natural world is a form of spiritual inquiry. For the first scientists, there wasn’t really a difference between asking a question about God and asking a question about the natural world. I think that’s closer to how I see his work. What’s really important is that he’s lost the ability to communicate his enthusiasm, how emotionally intense his relationship with nature is. You can relate that to the work of a director, but you can also relate it to teaching.

There’s that hackneyed phrase, “it’s best to lead by example.” It’s also best to teach by example and Clarence has lost the ability to do that at the start of the film.

In addition to all the performances from your actors, A Dim Valley features a pair of very different musical performances. Robert’s character watches the first one and performs the second. I’m wondering who or what informs your approach to directing musical performances, and how do you see these performances as responses to one another?

You know, it’s funny. Until you asked that question, I’d never really thought of them as responding to each other. It seems insane because they so obviously are.

For the first performance, there was the formal structure of being on a stage. There’s a certain closeness at a distance. The whole arrangement of the performance means that Robert is there experiencing it, but he’s not on stage. Even if the song is activating a sense of intimacy, there’s a divide there.

Then, the song Robert plays on guitar was one he wrote and sent me when we were working on Sabbatical. It stuck with me. It helped develop his character for me. Robert’s an incredibly charismatic performer, but he’s also a vulnerable, soulful person. I thought the song spoke to that part of him and would bring out that warm part of his character. It had to be the moment where he opens up. That karaoke scene has the feeling of separation, but here there’s a closeness. There’s a sense of acceptance that he hasn’t felt in a while. It’s the yin to the yang of that rejection he felt in the earlier scene.

To my knowledge Robert is the only actor who’s appeared in more than one of your films. Do you have an interest in building a stable of actors?

I don’t know. I think Robert and I have a pretty special creative relationship. He’s probably the one person who will continue to be in most things I do. It’s hard to build that level of trust as a director. You build that relationship with your assistant director, your director of photography — people who really have to know how to work with you — and I have that with Robert. It’s not that I don’t have it with other actors. It’s just that I feel like I have something with him that’s harder to access with other actors. It feels flexible, like it could go in a lot of directions. Robert is an actor who contains certain multitudes. I feel like I understand a lot of those different flavors and colors whereas a lot of other actors tend to feel very specific to me.

In giving me a very thoughtful answer about one actor, you’ve set me up perfectly for a very dumb question about another actor. The whole cast of A Dim Valley is excellent, but I wanted to focus on Whitmer Thomas in particular. Between this movie and his HBO special, he’s having a moment. That clicking thing he does with his jaw, was that scripted?

That’s actually in the script. It’s kind of a reference to Melora Walters’ character in Magnolia. She nervously clicks her jaw because she has TMJ and it’s a part of her whole courtship with John C. Reilly’s character. I love it, it’s one of my favorite movies. When I was thinking about this character, I kept thinking about this clicking jaw thing from Magnolia. It’s kind of funny, but it’s also annoying. That’s basically how Whitmer’s character is supposed to be at the beginning. He couldn’t actually click his jaw so he made this other sound. The sound designers, Matt Baker and Justin Sloan, meticulously went through and placed these clicks they’d recorded. It was really difficult and time consuming, but they did it.

As the characters are coming together for the first time and the revelations are beginning to take shape, Whitmer says, “I’m so confused.” There’s still a lot to come. Do you think he’s more confused or less confused by the time A Dim Valley has ended?

Less, and I think that character is probably the one who changes the most throughout the film. A lot of people tell me when they first watch the film that they expect he’ll be the villain. By the end, I think he’s built this awareness. I think he understands a lot more, but I’m not sure he’d be able to explain it.

Purchase A Dim Valley on Blu-ray

Follow Split Tooth Media and Bennett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)