In collaboration with Art & Trash, we present the text of Stephen Broomer’s Patreon exclusive video essay on Charles Henri Ford’s Johnny Minotaur, an unsung, haunting work of taboo motives and fierce, unapologetic eroticism

Queen Pasiphae slept with a bull sent by Zeus, and she birthed Asterius, who was called the Minotaur, at once infant and calf, half man and half bull. The oracles convinced King Minos to spare the Minotaur, hiding him in the Labyrinth, an inescapable maze that was built by the architect Daedalus at the Palace of Knossos. King Minos found a gruesome utility in the creature, first feeding the Minotaur his enemies, then feeding it sacrifices to ward off a divine plague. The hero Theseus set out to slay the Minotaur. In his quest, Theseus and Princess Ariadne, daughter of Minos, fell in love. Ariadne gifted Theseus a thread that would allow him to trace his path back to the exit upon killing the Minotaur; he succeeded, and in victory followed the thread back to love. More tragic turns follow, but this is the myth of the Minotaur from its birth to its death.

The Minotaur is a symbol of strength and virility, a reckoning with the duality of man, a beast of action, bereft of the gifts of the higher faculties. The Minotaur is masculinity unbridled. But it is also a figure whose meaning is completed by its environment, the Labyrinth, the archetypal multicursal maze, a maze that almost trapped its own architect. In the image of the Minotaur, man and maze become one. The Minotaur is in the loneliest condition: already the only of its kind, incapable of communicating with man or beast, it is locked away in a maze whose path can only be walked alone. The Surrealists were attracted to the concept of the Minotaur, for the creature was a triumph of instinct, but it was also an assemblage of incongruous parts, recalling the Comte de Lautremont’s statement that became a philosophy for the surreal assemblage: “the chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table!” The Minotaur inspired Albert Skira’s literary magazine Minotaure, and the image of the creature coursed through 20th century painting, in works by Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso. That century’s treatment of the beast was as a creature of complex instincts, unhindered by logic, driven by its impulses, a paragon of automatism.

Earlier movements in the arts had not been so generous to the Minotaur. The symbolist artist George Frederic Watts’ 1885 painting The Minotaur was inspired by a social crusade against child prostitution, lending another current to this dangerous, animal masculinity. The Minotaur watches the sea waiting for the arrival of young victims, the creature a collision of man and bull and sacrificial altar. Watts’s painting would later indirectly inspire Jorge Luis Borges to write about the Minotaur in “The House of Asterion.” In a role reversal, Borges’ Minotaur is the compromised and tragic hero, a hermit in an infinite house who awaits the arrival of his redeemer. Even as the avant-garde was adopting the Minotaur as an image of emancipated instinct, others were seeking to humanize and civilize it. The Minotaur could represent seduction and power, lust unbound, a sublime loneliness, or it could embody manipulation and predation. In this it is host to two competing roles: hunter and prey.

In the 1960s, poet Charles Henri Ford spent his summers in Crete. There he began to make a film that would be a film-within-a-film, a fiction film posed as a production diary, Johnny Minotaur (1971). It was inspired by the ancient myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, but Ford’s story would also involve definitively modern creatures, Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s Monster. Ford’s plans for the film were made possible by the collaboration of visiting friends and family, a local mask-maker, and young local boys to fill out his cast. Ford is the protagonist, in the sense that a fragmentary narration reflects his own thoughts and the camera is often subjective, in pursuit of intimacy. But he also has an on-screen surrogate, Karolos, played by Ford’s British friend Chuzzer Miles, which complicates the film’s documental overtures.1 Ford’s plans were loose and improvisatory, all in support of his desire to make a layered, self-reflexive work; he would later describe it in conversation with Jonas Mekas as a film operating on conscious and unconscious levels, offering that he had “made the film exactly like [he makes his] poetry … to have a graphic sequence and a rhythm.”2 Johnny Minotaur is a filmmaker’s notebook, a dream of a possible film, a doomed attempt at staging a classical allegory offered in a historic moment, as the longstanding impact of classical allusion was fading from culture. The result is a maze of sensations, confessions, taboos, interrogations, fantasies, and spontaneous inventions, a film with a willfully uncertain relation to fact. It is an erotic film, yet it is not ecstatic, but mournful: its makers, both the real Ford and the fictional Karolos, seem riddled with doubts about what the filmmaker has devoted himself to, the fading currency of allusion.

In America through the course of the 1960s, Ford’s identity was torn between the radical modernist literary circles in which he traveled and the Neo-Dada and postmodern art community forming on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He was long entrenched in the international community of modernist poets with its difficult forms, through his long history as a Surrealist poet, as a friend to Gertrude Stein and a guest of her Paris salons, and as a member of the literary set that surrounded The Dial, Minotaure, and View, the magazine he founded with his frequent collaborator, the film critic and poet Parker Tyler. But the 1960s found Ford freed up by the emergence of the underground, embracing the graphic immediacy of Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd. It was this sense of freedom that allowed Ford to pursue a form that some of his peers — among them, Jonas Mekas — felt was corrupting the utopian beauty of the underground film, a clever self-reflexivity inherited from mainstream art cinema, the film-within-a-film. Ford, as an aspiring filmmaker, was more interested in an arthouse narrative cinema than in the underground, and like his friends Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey, he felt less that he was a part of an artistic movement and more an individual freed by this moment to make whatever films he wished to make. To have one’s identity cleaved was also a part of Ford’s experience in another sense, as a gay man, aging into a turbulent society in which knowledge was contested terrain, a society with a declining interest in the past to which it would, inevitably, relegate him.

Related: Love In Wain: The Flesh And Blood Of Paul Morrissey by Brett Wright

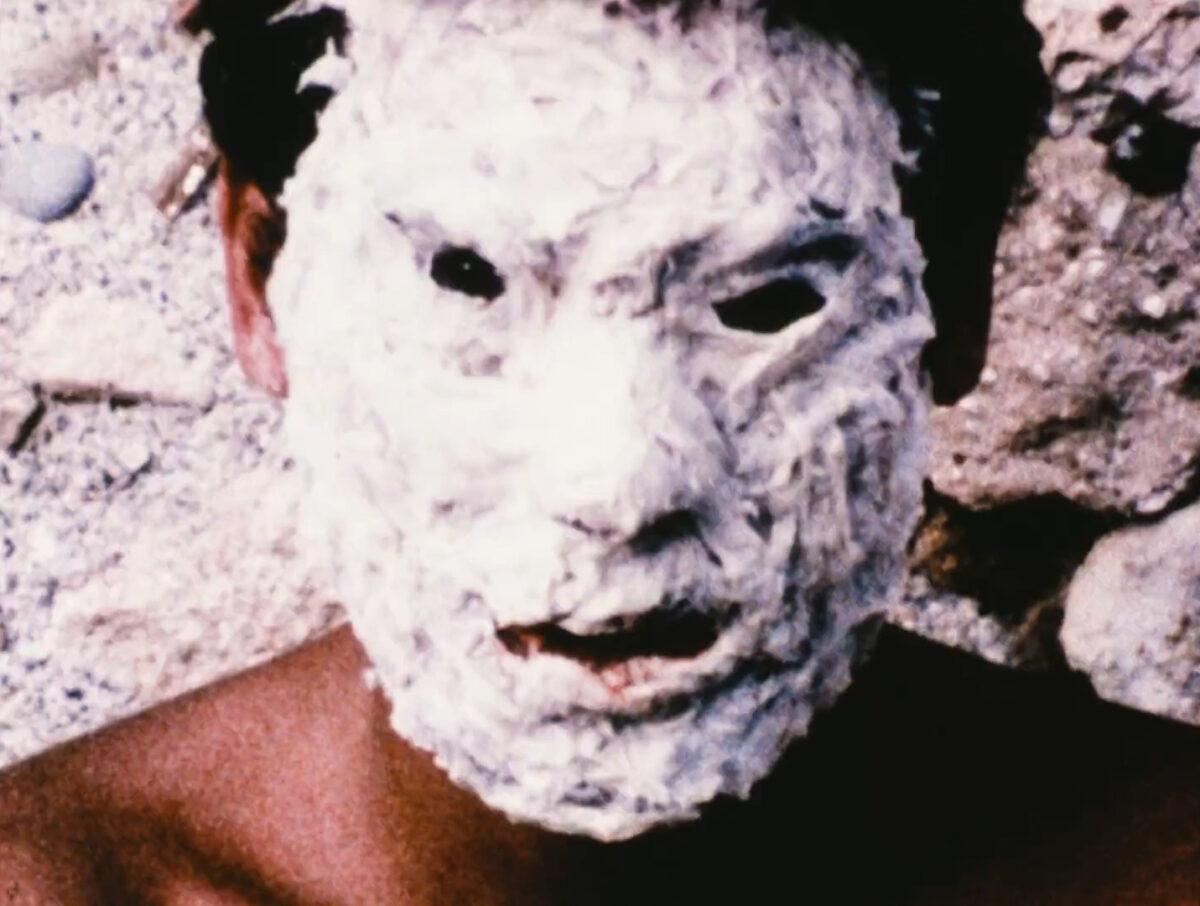

In Johnny Minotaur, fact and fiction blur totally in an apparent diary of a film that will never be made. Ford’s surrogate, Karolos, is a filmmaker who has come to Chania in Crete to stage an adaptation of the legend of the Minotaur. From the outset, the filmmaker’s task has been taken off course: Ford himself recounts a behind-the-scenes drama — his alienation from his lover, local artist and mask-maker Johnny, who spurns him to chase Ford’s niece, Shelley Scott, cast as Ariadne in the film. Subsequently, Ford has been driven to distraction by his relationships with the young boys in his cast, in particular, Nikos, who Karolos desires as both a lover and a son. In this, there is a predatory aspect to both the fictional film-within-a-film and the film itself: Ford’s access to these boys is facilitated by his wealth and their poverty. There are admissions of the degree of that poverty, for example, that Nikos is a street kid cared for by an older sister. The drama culminates in a series of voyeuristic encounters and the inevitable collapse of the filmmaker’s project, which ends in the ritual burning of the mask of the Minotaur. Throughout, scenes depict the social rituals of the boys; staged scenes of fighting and bathing; and the trials of Karolos’ Minotaur, whose story, differing greatly from the classical tale of Asterius, is closer to a picaresque in which the Minotaur is an adolescent naif who escapes from Minos in search of the companionship of other young boys. The project is further contextualized by conversations between Karolos and fictional reporters, visiting friends, and even Ford himself.

Through the course of the film, Ford presents a series of colliding classical and modern allegories. His desire to make allusions to Count Dracula and Frankenstein suggests themes of, in the case of Dracula, vanity, seclusion, and predation; in the case of Frankenstein, the reassembly of the body, animated and reawakened, given new vitality, like that found by new parents experiencing a second childhood through their own children. This metaphor holds an ugly suggestion in Karolos’ incestuous overtures to Nikos. The filmmaker seems aware of the irony of telling the story of Dracula in the sunniest place on earth. Through Karolos, Ford speculates on the rhythms of life in Chania, and what he perceives as the poor manners of the Cretans, which he more or less admits is his reaction to the tepid and taunting behavior with which the young men meet his desperate expressions of desire. He seems to know that to them, he is Count Dracula, much as any sex tourist is a kind of vampire preying on poor boys under the Cretan sun. Karolos, much like Count Dracula, doesn’t see himself as evil but as an outsider, and he voices these pederast desires in a thread of self-pity, portraying himself as a victim of the teasing of Nikos, whom he also wishes to adopt. As Dracula, he wishes to feed on Nikos; he is also Frankenstein’s monster, decaying flesh in search of a reawakening. Here dwells a link between Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the myth of Galatea: to the filmmaker, the boys are sculptural, like Johnny’s papier-mâché mask of the Minotaur. He commands the stone to wake, to love this man.

Johnny Minotaur is a film of classical allegory; it is a film about the use of classical allegory; and finally, it is a film about the uselessness of classical allegory in a changing world. Classical allegory had been a central tool in the intellectual life of the 20th century, and in particular, in the work of gay filmmakers, grounding their eroticism in an ancient lineage of courtly love and absolutism. The classical allusion was a marker of eternity and continuity. As Orpheus was for Jean Cocteau; as Hippolytus was for Gregory Markopoulos; as Narcissus was for Willard Maas, the Greeks were an ideal for gay filmmakers because the myths were so potently queer, fables of beautiful bodies wrestling with temptations, mystical evils and the conspiracies of the gods. Allusions to ancient tales were not restricted to a Greek polytheistic mythology: Biblical allegories served a role in the evolution of queer cinema, as Salomé did for Alla Nazimova and Charles Bryant (Salomé, 1923), as Sodom did for James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber (Lot in Sodom, 1933). Charles Henri Ford made Johnny Minotaur at a time when an emerging generation of queer filmmakers, such as Tom Chomont, Ed Owens, and Warren Sonbert, were beginning to make work that dealt more directly with their own experiences as gay men in the contemporary world. The rebellious carnival of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963) was confrontational in its sexuality, but it had been anything but intimate; the new generation of gay filmmakers were exploring such intimacies. The cloak of classical allegory was fraying, and soon, with work like Michael Wallin’s The Place Between Our Bodies (1975), the ‘observational present’ of diaries and pornography would intersect to fulfill what the prior generation’s allegorical fantasies had suggested, an explicit confrontation with homosexual eroticism. For Ford, this kind of intimacy is elusive: even in its most explicit passages, Johnny Minotaur is marked by a voyeurism that speaks to the distance between Ford’s aging sensibilities and the young hearts on the other side of the camera. Perhaps Ford was reflecting on this distance when he wrote, in a poem titled “The Minotaur Sutra,” “Meshing and timing / subvert convert divert and / leave without goodbyes.”3 Neither Ford nor Karolos will mark these boys in the meaningful, romantic way that they wish to: they are phantoms of a vanishing order, sex tourists who come and go, one much the same as the next, and the self-degradation of their desperate, cloying need for loving attention can only push them further to the recesses of memory, to leave without goodbyes, better off forgotten. To say goodbye does not matter: the boys would be deaf to their goodbyes.

Johnny Minotaur was not the only film of its kind to emphasize the growing gulf between contemporary experience and myth: another self-reflexive film, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Notes for an African Orestes (1970), is a production diary that attempts, in the footsteps of Pasolini’s own classical allegories and Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus (1959), to transplant the myth of Orestes to Africa, in the process confronting the filmmaker’s own patronizing Conradian fantasy of a primeval, tribal continent. Pasolini’s film is an admission of the impossibility of classical allusion to wrestle with the complexities of a contemporary world. Ford’s allegories, more complex as a collection of classical and modern monsters, but far more indirect in their staging, are more personal than Pasolini’s and become a cause of suffering that transcends the challenges of storytelling and filmmaking. Other classical allegories are brought into play: for Ford, the Cretans are more like Talos, the mythological Cretan automaton formed from brass, who would heat himself up and embrace strangers who landed on the island, a fatal and masculine variation on the Sirens, an oven in the shape of a man. The classical allegory serves to not only declare his lust, but to enhance it, for it finds expression not only in narrative but in the mise-en-scène: it is evident in an exaggeration of features, as in the comic curvature of the plastic penis that Nikos plays with, the hung penis as comic perversity-in-extremity, curved to the golden mean.

Related: Su Friedrich Reflects On 30 Years Of Sink Or Swim by Robert Delany

While the film-within-a-film conceit lends Johnny Minotaur a thematic trajectory, Ford’s visual approach is informed by a style close to his contemporaries in the New American Cinema: discontinuous, rapidly shifting imagery, stray passages like fragments of consciousness, as in the diary films of Jonas Mekas and Marie Menken, albeit chained to sustained discussions of the themes, and palace intrigue surrounding the production of the film-within-a-film. With few exceptions, Johnny Minotaur is in a continuous state of montage, with prolonged dialogues, some scripted, some spontaneous, playing under a steady stream of observed moments from life in Chania. Throughout, Ford engages digressional motifs to provide a structure. For example, a swinging hammock, first seen being used by two adolescents to swing a third, becomes a metaphor for Ariadne’s thread, a spun web, occupied for the most part by a nude woman, aforementioned niece Shelley, playing Ariadne; a slide projection alternates rapidly between images of a bare-chested woman and a satyr-like figure with an erect penis, while a silhouetted hand mimes masturbation; in an extended sequence, two sailors dance in a bar, putting on a drunken, ecstatic, Dionysian performance of male companionship that is ambiguously erotic while the camera zooms in on the details of their bodies. Such formal digressions provide structure to a series of encounters including pageant-like executions and battles, and long-take portraits of Ford’s Chanian community, many of them turning erotic, with his subjects masturbating, most memorably, thrusting into a melon. Karolos alternately describes the filmmaking process as smooth and frustrating, and while dramatic staging and planning is underway, the filmmaking itself becomes an excuse to do what Ford would rather be doing, intent leering, in contrast to the scripted Karolos with his insistence on theme and story.

The melon masturbation sequence marks a turning point in the film: until this point, the film’s sequences have focused on Karolos’ social experience making his movie, with long digressions about Johnny’s education, the attempted adoption of Nikos, and an orgy, seen in slides, between the Chanian boys and tourists, all interspersed with ritualistic tableaux, frolicking battles, and diaristic behind-the-scenes footage. When the figure finishes thrusting into the melon, he sticks a blade in it, a casually violent gesture that initiates a brutal catharsis, as the themes of the Minotaur myth — slavery, barbarism, torture — come to the fore. A naked youth, wrapped in Ariadne’s thread, castrates himself; a cloaked figure, symbolic of the fates, kneels next to the boy’s body, stage blood over his crotch. In subsequent scenes, as Johnny makes papier-mâché masks, Ford’s friend Allen Ginsberg offers an interpretation of the myth of the Minotaur as a dissolution of the body into nothing; the expansion of consciousness to include the void: to embrace fear, death, the unknown. To realize that matter, self, and all things are empty; a great negation of all real things. The decadence of this life is empty too. The film becomes Ford’s confrontation with another void, the maze of experience that is leading, inevitably, to the dissolution of myth. The film becomes impossible: Karolos retells the story of Johnny and Shelley’s affair, in discussion with novelist Charles Haldeman, a friend of Ford’s who served as the film’s screenwriter. As Haldeman hears Karolos’ account, he is in the process of posing nude for Johnny, to whom Haldeman translates Karolos’ request that Johnny leave the castle. The film reveals its own maze of relations, as the surrogate asks the screenwriter to evict the art department on behalf of the filmmaker, all within a context that betrays its own staging. Did Haldeman, as screenwriter, conceive of the entire scene? This indirection also speaks to an overarching theme, inherited from the ancients, that of the enduring worth of storytelling: tales passed along, fictionalized and transformed between characters and between tongues, gathering new meanings, interpretations, and applications. Even the modest, unexceptional betrayal that has derailed Ford’s narrative deals out the mode of orality that had long served as a vehicle for the survival of culture.

Despite its discursive form — as a fictional film-within-a-film — it is easy to perceive Johnny Minotaur as lacking in self-awareness, given the various ways in which Charles Henri Ford, both behind the camera and through Karolos, appears compromised by lust and need, from his incestuous fantasies and leering camera, to Karolos’ vampiric presence on the sun-soaked beaches of Crete. Yet, Ford is painfully aware of the declining valuation of classical knowledge. His own interpretation of the Minotaur myth, the debates of his friends, which range from the studied to the juvenile, are made possible by a shared sense that myth underpins all conception of the real, that fantasy is a bridge to greater truths. Ford was never really celebrating the classical allegory when he set out to make Johnny Minotaur. He was mourning it. Ford is losing his grip on the contemporary world, and the emotional unraveling of his surrogate, the impossibility of completing this film-within-a-film, are signposts of a changing order, tombstones for the resonance of the ancient. As the currency of his allusions declines, with them fades insight. This mourning is laid bare in a late poem of his, “The Face of the Earth.”

The world’s a mirror, to break it is to die.

The way of death is wider than the road to glory.

Man can perish through love alone.

But the wine of glory without the bread of love

Turns the tongue to stone.

The rope, the plank, the poem,

Love, life, glory, call it what you will,

Draws to a close and gives you a chilly feeling.

“The clouds are looking for the wind!”

They are going, and the children are going.

Envoi and farewell…

Perhaps we’ll meet in hell or heaven.

And there’ll be other eyes to open

And see what else there is to see

On the face of the earth that once belonged to me.

Become a Patreon supporter of Art & Trash to view Broomer’s video essay on Johnny Minotaur (1971)

Broomer is also the founder of Black Zero, a home video label that specializes in Canadian underground film. Explore its collection of films at blackzero.ca.

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)

- Parker Tyler, Screening the Sexes: Homosexuality in the Movies (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1972), 160.

- Jonas Mekas, Movie Journal (column), April 22, 1971, 65.

- Charles Henri Ford, “The Minotaur Sutra.” BOMB 34 (1991).