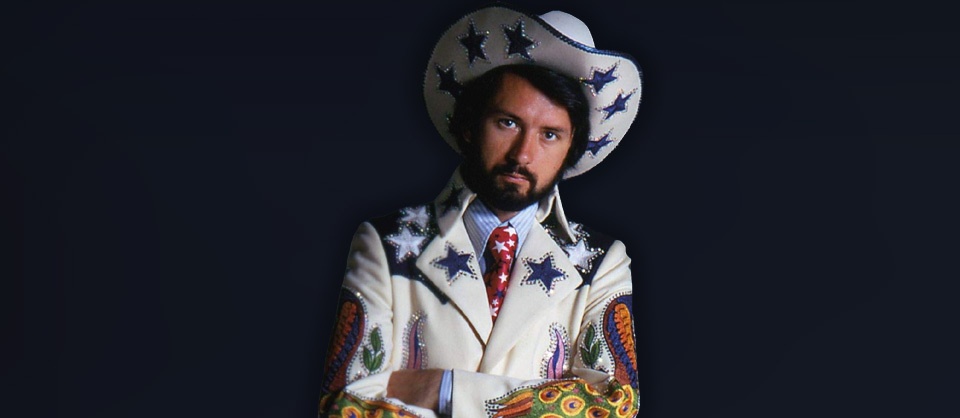

After severing ties with his Monkee Mike persona, Nesmith rebuilt his image as a cosmic country troubadour

When Michael Nesmith died in December 2021, tributes poured in for the former Monkee, who just weeks before had finished a farewell tour with his sole other surviving bandmate, Micky Dolenz. Countless images of Nesmith in the green wool cap he donned as a Monkee flooded social media and news tributes. Monkee Mike will always be Nesmith’s most remembered role, a truth he had a complicated relationship with for most of his life. Confining Nesmith’s legacy to his days with The Monkees does a great injustice to an incredibly complicated man, one whose accomplishments range from a robust solo career to being credited as the inventor of the music video. While The Monkees provided Nesmith a platform to launch this work, his most compelling legacy came when he traded the wool cap for a Nudie suit and became a pioneer of cosmic country.

Michael Nesmith left The Monkees on April 14, 1970, following two albums made as a trio after Peter Tork bought out his contract and left the group in 1969. By these later Monkees albums, coming after the end of their TV show and the colossal failure of their film Head (1968) with contemporary audiences, Nesmith had already developed a strong individual identity within the group. He was the member most responsible for the band winning creative independence over their music in 1967, and he steadily grew in influence from that point with compositions that could be either startlingly psychedelic or strongly country-leaning. It is a progression that leads relatively naturally into his first trio of post-Monkees solo albums1, all released alongside a group of musicians called The First National Band.

Released in June 1970 with longtime Nesmith collaborator Orville “Red” Rhodes, alongside John Ware, and John London, Magnetic South was the debut Michael Nesmith and The First National Band record. There is an urgency to the album, suggesting that he is keenly aware of just how important it is to make every note count as he tries to eschew his Monkee image and be taken seriously as a musician. It plays like a manifesto, or an introduction to Mike Nesmith, not the wool cap-wearing character he portrayed on TV. Magnetic South begins with a three-track run that sweeps from samba rhythms to a bittersweet ballad, finishing in one of Nesmith’s most gripping rockers. In just around seven minutes and presented as if it were one continuous song, Nesmith lays out a rich assortment of musical samplings that still do not even begin to scratch the surface of what the rest of Magnetic South has to offer.

Related: Harry Nilsson’s ‘Aerial Ballet’ Is An Under-Appreciated Masterpiece by Craig Wright

Nesmith crafts a self-contained world that manages to be both intimate and sweeping. While many artists seem unsure of themselves in their first solo outings after leaving famous and established bands, Nesmith sounds astoundingly sure of his direction. His confidence almost leaves one taken aback when considering he just left a band that was often criticized for and sometimes not allowed to play on their own records. Even though The Monkees had control over and played on their own records as early as their third album, Headquarters, the accusations of being “fake” musicians dogged them for years to come, as did the expectations inherent in maintaining their Monkee personas. Nesmith shatters those expectations by eschewing the catchy pop hooks of Monkees tunes for more complex structures and the occasional darker lyric, like references to a girl sleeping on the railroad tracks and her entire town drowning in “Little Red Rider.” These qualities that would feel quite out of place on most Monkees records feel entirely natural on Magnetic South.

What is perhaps most fascinating about Magnetic South are the points where it feels near-satirical. As a Monkee, Nesmith’s Texan heritage was gratuitously played up, meaning that a country album would have been well within the realm of possibility for his fictional persona, too. Nesmith seems to embrace that, but only to poke fun at it and use it as a vessel to further his own statement of identity. He leans so far into the country stereotype at some points, like yodeling on “Mama Nantucket,” that it borders on a mockingly ironic tone. At the same time, it manages to feel entirely genuine, blurring the lines between the real Mike and the image he cultivated as a Monkee. He comes out so confidently contradictory on the album, which opens up questions about whether that too is an act, an extension of the persona. He even breaks the fourth wall, not unlike how he frequently would in the Monkees television program, exclaiming that, “We’ll be back right after you turn the record over!” on the A-side’s final track, “First National Rag.” Nesmith remained so enigmatic through the rest of his life that it remains difficult to separate the two, but it makes his solo work, and especially that on Magnetic South, all the more engaging.

The record did help Nesmith gain some acclaim as a musician in his own right, even leading to the First National Band playing alongside Gram Parsons and his new band, The Flying Burrito Brothers. If Magnetic South is Nesmith’s strong start and declaration of values, 1970’s Loose Salute is where he settles into his role as a wry Western storyteller. The urgency of the first entry in the trilogy transforms into a swagger. On Loose Salute, Nesmith takes a much more experimental approach, really leaning into the psychedelic elements that define the “cosmic” side of cosmic country. From the expansive bridges of “Thanx for the Ride” to the hypnotic swells of “Tengo Amore,” Nesmith explores unturned stones within his own country world, seeking to make something more sonically stimulating and intellectually engaging to pair with his increasingly introspective lyrics.

Loose Salute also takes on a contrarian tone, a trait that would become the trademark of Nesmith’s creative output. From this point on, the unexpected becomes expected. As with any middle entry in a trilogy, it could be easy for Loose Salute to be overshadowed and overlooked; however, this is perhaps the most indicative record in this First National Band trilogy of what Nesmith would become. Not only did he pioneer the cosmic country subgenre, but he constantly pursued other multimedia experiments, from music videos, to television programs like Elephant Parts, to creating soundtracks to go along with books he wrote, intending them to be enjoyed synchronously. All of his most significant accomplishments came about from a desire to push his own boundaries and take the most unexpected turn he could, and while that tendency was always simmering, it boils to the surface for the first time in Loose Salute. Most directly, the more experimental parts of the album foreshadow 1972’s deeply trippy Tantamount to Treason Vol. 1.

Related: The Treasure Of The Oneness: Stephen Stills & Manassas by Breanna McCann

Nevada Fighter (1971) is a fitting conclusion to this trilogy. From Magnetic South to here, it feels like Nesmith lived a lifetime despite it being a mere 11 months between the first and last entries. What is most felt on this final First National Band album is a restlessness. It starts with the driving “Grand Ennui,” which does not feel like a coincidence. Nesmith has just hit his sweet spot — a perfect blend of cosmic and country elements to showcase his wry witticism. But he’s already listless. The album, much more low key than its predecessors, shows a desire on Nesmith’s part to find the next unconquered horizon.

Already there is a noticeable difference in the way he writes thematically similar songs. The biggest hit of Nesmith’s solo career, the stunning “Joanne” from Magnetic South, is a beautiful, lamenting love song with an abstract approach. There is considerable room left to read between the lines of Nesmith’s lyrics and interpret the events that transpired between Nesmith’s narrator and Joanne. On Nevada Fighter, Nesmith has similar love songs, such as “Texas Morning” or “Propinquity,” where he retains the heady lyrics of “Joanne” but applies it to more concrete, detailed stories. Interestingly, “Conversations” from Loose Salute provides a midpoint between the two both in its lyrical approach and chronology, further establishing some sense of progression within the trilogy despite Nesmith’s surety from the outset. The differing approaches are alternate paths to the same destination, and it provides an interesting point of comparison to see the ways he evolves and changes his approach throughout this brief era of his solo career. Through the entirety of the trilogy, Nesmith revels as the bemused narrator at the center of his strange, Western cosmos. Nesmith’s ability to wrangle with philosophy alongside an entrancing narrative is a hallmark of his songwriting, and it is so evident in these first three post-Monkees albums. The First National Band albums are the key to understanding his later work and the exploration and worldview inherent in it. While they act as somewhat of a training ground for Nesmith as he steps outside the world of The Monkees, he never once stumbles. The First National Band trilogy is better understood as a manifesto of an artist expressing and embodying who he wants to be, rather than as a search for who he is. It is a complex performance that comes across with incredible confidence in his musical identity.

If anything could define a figure as enigmatic as Michael Nesmith, it would be the consistent drive to defy expectations and turn them on their head. Many of the songs featured on these three albums were written while he was still in The Monkees, which gives further credence to the idea that Nesmith always had some grasp on his own artistic identity. The First National Band trilogy stands as his crowning achievement and unequivocally establishes Nesmith’s role as a true pioneer. Nesmith showed that country didn’t need to be confined by the limits or expectations of genre. His First National Band recordings constantly take familiar country and Western sounds into new and unexpected directions. Just when a listener thinks they have a grasp on him, he goes an entirely different way. This unpredictability became a constant throughout his career, providing a clear link from these first post-Monkees albums to his final solo works decades later.

It is rare to see an artist present their artistic vision and identity so clearly and confidently from the outset that it remains largely untouched for nearly 50 years, but Mike Nesmith was never one for convention. The First National Band trilogy is ripe for questioning who Mike Nesmith was and whether he really believed in it, but the original Cosmic Cowboy remains as enigmatic as the moniker suggests, and the intellectual and philosophical engagement that his music requires of listeners keeps it as compelling as the day it was recorded.

Stay up to date with all things Split Tooth Media and follow Breanna on Twitter

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)

- In 1968, while still a Monkee, Nesmith released an instrumental album entitled The Wichita Train Whistle Sings as a side project.