As the mumblecore bubble was beginning to burst, Ross, always an outlier within the movement, experimented with more elegant visuals and his most unorthodox narrative yet

Despite receiving near-unanimous praise from the limited audiences and critics who saw it, Frank V. Ross’ Tiger Tail in Blue failed to gain professional distribution upon its release, ultimately earning accolades as one of 2012’s “Best Films Not Playing in a Theater Near You.” It can be said with confidence that there are few films from this past decade more deserving of discovery in the 2020s.

Tiger Tail arrived as the “mumblecore” bubble was beginning to burst. At this time, many of the filmmakers associated with mumblecore since the beginning were starting to distance themselves from their DIY roots and that dreaded m-word. Some began pursuing more studio-based work, making films that had actual — in some cases substantial — budgets. Many began crafting films with more traditionally structured narratives, some even venturing into genre territory. This period is also bookended by the releases of Lena Dunham’s breakthrough Tiny Furniture (2010) and Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach, starring and co-written by Greta Gerwig, 2013), possibly the two most popular and successful films to be associated with mumblecore. These films are distinct for taking many of the narrative and thematic touchstones of the mumblecore movement, genre, wave — whatever you want to call it — and crystalizing them into more polished and digestible presentations.

With Tiger Tail in Blue, Ross went in a different direction than many of his peers. Where his previous film, Audrey the Trainwreck (2010), perfected Ross’ particular style of orchestrated haphazardness, Tiger Tail shows a new restraint. The film demonstrates a greater interest taken in the technical aspects. The film is stunning. Its visuals are more elegant than any of Ross’ scrappier early productions, thanks in large part to his collaboration with cinematographer Mike Gibisser. Its score, composed by John Medeski and Chris Speed, is heartbreaking — especially the melancholic rendition of “Auld Lang Syne” that plays during the film’s New Year’s sequence.

But Tiger Tail also found Ross, always an outlier within the movement, experimenting with a more unorthodox narrative, even by his standards. The film follows Chris (Ross) and Melody (Rebecca Spence), a recently married couple who are stuck working opposite schedules. Melody teaches high school English, while Chris, a writer, pursues his passion from home by day and waits tables at night. Taking place about a year into their marriage, the honeymoon phase has ended and things are beginning to settle. Their love is real, but money is tight and time is tighter. The struggle to see each other between shifts causes a strain, particularly on Melody. She often has to go to parties alone and stay up late “rallying” to catch Chris for a few minutes before bed. There is also a new waitress at Chris’ restaurant, Brandy, whom he gradually develops a flirtatious relationship with.

Ross has never shied away from depicting the hard work that goes into sustaining a relationship in his films. But Tiger Tail looks deeper into the more interior aspects — the unfathomable imaginative processes that its lovers must work through to keep it all together — than any of his previous work. The film was an incredibly personal project. He conceived Tiger Tail during the early years of his own marriage while working opposite schedules from his wife and even staged the production in his own apartment and the restaurant where he was a server.

Moving swiftly through fall and winter in Chicago, Ross draws a unique attention to how time flies by his characters, building a swift, elliptical rhythm out of their daily routines. The effect created by the film’s brisk pacing is presented neither as a sentimentality for days gone by or a sweeping, Malick-like profundity, but a practical awareness to how these characters live in time. Tiger Tail evokes not only the physical wear-and-tear of working for a living, but also the mental weight placed upon these individuals. Chris and Melody are rarely able to find time to reflect or even collect themselves throughout each day. As weeks blur together and holiday decorations go up and come down, they are lucky if they can sneak away to grab a donut or go sledding on a day off, let alone get a clear idea of where they stand in any larger perspective.

Throughout the film, Ross shows Chris and Melody to be two imaginations set out of alignment in opposite directions. Chris is more self-centered and gets aggravated over all the little things throughout his day. He nitpicks about his customers and acts passive aggressively towards Melody. His venting proves to be an isolating exercise. He turns conversations into monologues, unaware of the exhausting effect his rants have on his listeners.

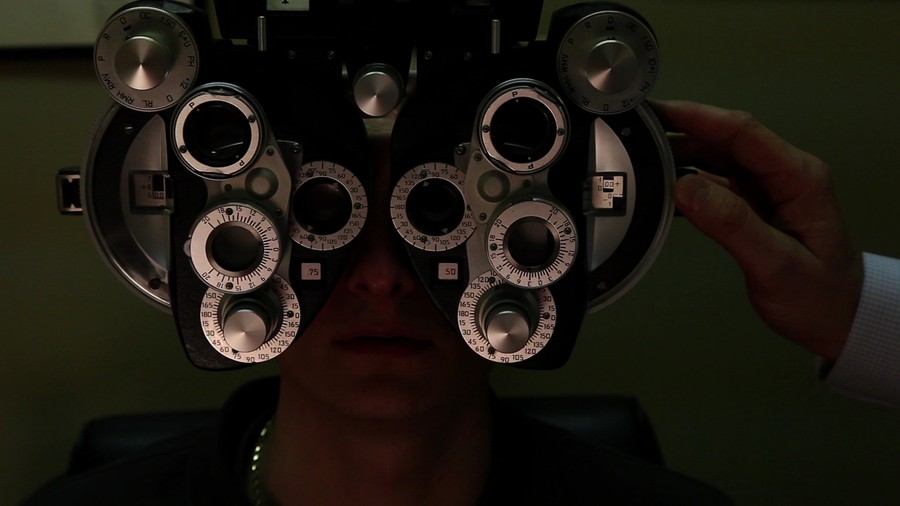

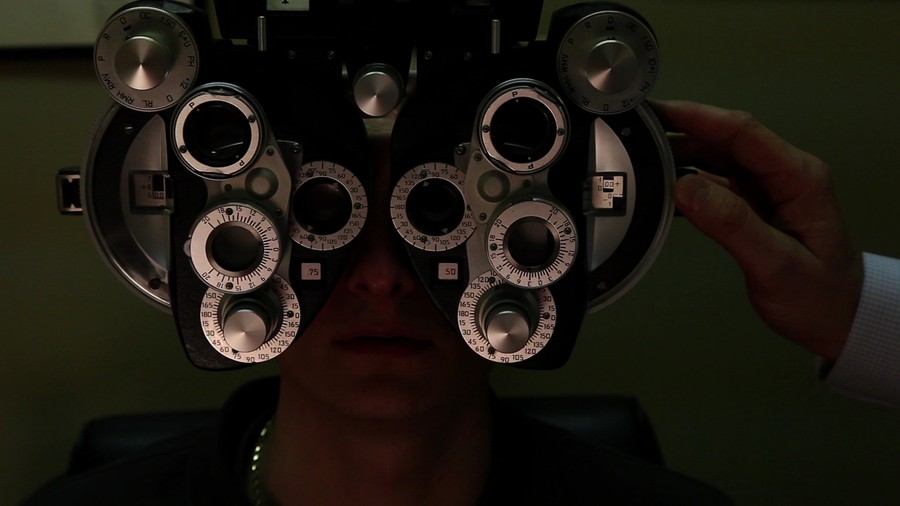

Melody, on the other hand, is preoccupied with more urgent issues. With Chris writing during the day, she takes the brunt of the financial burdens. She is dissatisfied with her job, but her worries over her profession are not solely concerned with her happiness — she isn’t even certain she will have her position next year due to budget constraints. Melody internalizes her frustrations more than Chris and sends a lot more back when confronted. When Chris starts an argument with Melody over getting a ride home from the eye doctor, the event provokes an unloading of her frustrations with her demanding work schedule, lack of a sex life and career uncertainty. Scenes of Chris and Melody addressing one problem tend to snowball into arguments about all sorts of contingent issues. When Chris sheepishly tells Melody he can’t afford his half of the rent, the scene turns combative and nearly leads to a discussion of what Chris would be willing to give up in order to help more with finances. Ross also stages this argument as Melody is leaving for work, ending the scene with an unresolved tension that festers until Melody calls shortly after to reconcile with her husband.

Like Ross’ characters, we viewers don’t always have time to catch our footing within each scene. Tiger Tail is a busy film that moves at a swift pace and plays out like a series of double takes. Part of Ross’ greatness, since his 2005 breakthrough Quietly on By, is his ability to create the sensation of time passing us by as we watch his characters going about their routines. We feel as if we missed something that was there all along but couldn’t exactly recognize it until the film offers a later opportunity for reflection — callback moments that make the realizations hit that much harder.

For his characters and viewers, Ross structures Tiger Tail in a way that insight strikes mostly through roundabout, tangential means. Of particular note, most of the film is presented as a prologue. Entire lives unfold onscreen before Ross flashes the title card around the 50-minute mark. We watch Chris and Melody go to work each morning, get ready for bed and then do it all over again. They share tender and conflicted moments and Chris strikes up a rapport with a fellow server — who looks just like Melody — then we have to recalibrate our understanding of everything we just experienced during Ross’ final act. A great deal of the film’s rhythm is established through doubled actions and match cuts that parallel Chris and Melody’s days against each other. Ross seamlessly connects a scene of Chris doing Bishop’s knife trick from Aliens (1986) while waiting for a day’s worth of writing to print, with a shot of Melody photocopying materials for class. While Chris kills time waiting for ink to dry on his accomplishments, she looks exhausted — like she has a great deal more work ahead of her.

As with Ross’ previous films, notably Hohokam (2007), Tiger Tail places great importance on the brief pockets of time where characters can take a moment to collect themselves before diving back into the daily grind. But these moments are harder to come by for Chris and Melody. Following their argument over the ride home from the eye doctor, Melody does pick Chris up from his appointment in the film’s first scene following the prologue. With Chris’s eyes dilated, Melody suggests they sneak off to share a coffee and a donut (a “tiger tail” donut) before they both have to return to work. During this scene, Ross allows the film to breathe along with its characters. The tone and pacing settle down as Chris and Melody casually walk and talk, eventually resting against their car to eat. Chris begins one of his rants about an evening he requested off — inviting Melody on a date night in the process — due to what he considered a customer’s obnoxiously early request for a reservation at his restaurant. Melody accepts and they both realize they can’t remember the last time they had dinner together.

Chris and Melody’s break is short-lived, but formally, this slight aberration in Tiger Tail’s rhythm sends reverberations through the rest of the film. As they get ready to go back to work, the film cuts away to shots of other people and details on the streets and sidewalks around them. The rhythm picks up again as our vision is drawn away by roaming views of their surrounding environment. The effect is strange, especially when we realize this is the first time that Tiger Tail has deviated beyond the short-sighted scope pervading over its extended prologue by breaking away from Chris and Melody for a substantial amount of time. The film covers so much ground that it is jarring to recognize how little we have seen of the world around its characters. But with this awareness, the film also introduces a new potential for tangential experiences within the narrative, some of them troubling and dangerous.

***

“Our life is not so much threatened as our perception… We do not know today whether we are busy or idle. In times when we thought ourselves indolent, we have afterwards discovered, that much was accomplished, and much was begun in us.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Experience” (1844)

There is a passage in Ross’ screenplay for Hohokam that anticipates certain ideas later developed in Tiger Tail in Blue. Following a fight with his girlfriend Lori (Allison Latta), Anson (Tony Baker) passes a beautiful woman outside of his apartment. As we see it in the film, he checks her out with a quick glance and goes on with his day. We see a brief shot of the back of her legs as she walks on, but then she is never seen in the film again. The encounter takes place in an instant.

Shortly after, Anson goes to buy Lori a present as a peace offering.

These two events have no direct relation as they appear in the film. But in Hohokam’s screenplay, Ross details the nuance behind Anson’s fleeting attraction to the passing stranger:

“Every man has his own definition of a beautiful woman, it varies with circumstance and is ever changing, an image [that] cannot be defined only seen… Anson himself happens to like the backs of a ladies legs, back of the knee, the hip as it stresses slightly to take another step. For lack of a better word and at the risk of cheapening this moment: Anson just fell in love… Let’s watch him go back to work as if none of this ever happened. First let’s say: when this happens to a guy and that guy happens to already be in love with someone like Lori, moments like these remind you why you love her, and starting right now Anson loves Lori more than he ever has.”

The written scene builds a connection between this tiny moment and Anson’s later efforts to make up with Lori. But it is Ross’ imagining of Anson’s interior process that is most significant.

Ross’ narratives, in general, avoid major life-altering crises and epiphany moments. In Hohokam’s case, Anson’s attraction to another woman leads to a realigning and sudden deepening of his feelings for his girlfriend. The experience is described as having a disorienting effect upon him, a sort of modest epiphany, as Ross’ language conveys a sense that Anson has reached this new understanding without entirely comprehending what has taken place. While none of this shows directly in Hohokam, in Tiger Tail, Ross manages to dramatize this roundabout, interior process on screen to provocative effect.

One may notice that Rebecca Spence is listed in the credits rather ambiguously as “The Brunette.” This is because Spence plays two characters: Melody, and Chris’s flirtatious coworker, Brandy, for most of the film. (At crucial points in the narrative, Megan Mercier takes over the role.) We see Chris flirting with what initially appears to be a flashback version of Melody. These scenes are distinguished by Gibisser’s richer color schemes, contrasting the sombre blue tones that pervade over the rest of the film. Initially, it appears as if we are seeing the scenes of how Chris and Melody met and fell in love being set against their contemporary situation as a married couple. But as the film progresses, and upon reflection, the details hint otherwise. Scenes of Melody picking Chris up from work are followed by Brandy dropping him off at home (notice the different colored beanies), or we will see Chris sharing a New Year’s kiss with Spence’s Brandy while Melody watches the ball drop alone at a party that Chris arrives at later.

“I wrote Tiger Tail for Rebecca based off working with her for just one day [on Audrey the Trainwreck]… I didn’t direct Rebecca much. In the script, the characters are listed as ‘The Brunette’ and ‘Melody.’ I think writing it like that helped her enough where I didn’t have to give her much direction. My favorite thing to do is just sort of trust people and be surprised.” — Frank V. Ross (Courtesy of Frank V. Ross)

The moment it is revealed that Spence has been playing two characters at the end of the film isn’t treated as anything so simple as a narrative “twist” — that isn’t to say it isn’t shocking. But to feel the moment’s full effect is to recognize that the sensation it elicits is not supposed to be entirely understandable. Tiger Tail has drawn comparisons to Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), in which one character is played by two actresses. But what Ross does with Spence’s dual-role is less Buñuelian surrealism and more akin to the oddly miraculous conclusion of Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy (1954). In Rossellini’s film, a wealthy and distant British couple spend their entire trip abroad bickering, avoiding each other and flirting with other people before planning for divorce. Then, at their lowest point, a shock reconnects them in a sudden and passionate bond during the film’s melodramatic final moments. Rossellini said the epiphany ending in his film is a miracle, but it is “scarcely there.” He surrounds the event with “confusion and hysteria” by staging the scene in a busy crowd and throwing the audience into it in a disorienting manner. We don’t get the feeling that their problems are solved, only that a new understanding of their love for each other has been breached by the characters just as the credits roll. The real work will be done later.

Tiger Tail’s climax is equally “scarce.” Chris doesn’t have a Hollywood-style epiphany where everything becomes entirely clear after a near-affair with another woman. He doesn’t go romantically charging back to his wife. When Mercier takes over the role of Brandy in the film’s final minutes, Chris is struck by a blast of confusion, rather than clarity, that scrambles his perceptions. Much like Anson in the Hohokam script passage, Chris appears stunned and unable to grasp the situation in front of him. He fails to retreat from the event with Brandy with any sort of grace, yet this eventually leads to a realignment of his attention when he returns to his wife.

Tiger Tail ends with Melody on her way out the door to work, presumably the next morning. When she appears in the hallway of their apartment dressed in Western garb with cowboy hat and boots, Chris stops in his tracks. He and Melody invent a scene together as she assumes the role of a tough talkin’ Westerner in their living room. They start to dance and Chris joyfully sings to her. It is a moment undisturbed by life’s problems, uninterrupted by petty complaints or arguments over rent or rides home. We see two people purely inspired by each other’s company. Then Melody heads out the door to her car and Chris begins preparations for a day of writing.

The final scene is a small, “stolen” moment — as Ross describes these slight breaks in his characters’ often grueling and disorienting routines — but through it, Tiger Tail in Blue evokes life’s most mysterious ways of refreshing itself. The film finds hope for Chris and Melody’s relationship as they recognize and make the most of this small opportunity, demonstrating a potential for putting new understandings into action in the process.

Stream Tiger Tail in Blue here

Follow our series on the Films of Frank V. Ross here:

Follow our series of The Best of the 2010s in Film here:

Follow Brett on Twitter and Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)