“I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s damn difficult to make a film. It’s such a terribly unnatural journey into all the actor’s personal lives… I try to find some kind of positive way to make a world exist like a family — make a family, not of us behind the camera, not of the actors, but of the characters.”

— John Cassavetes in Cassavetes on Cassavetes, Ray Carney

John Cassavetes holds an uncomfortably iconic place in the history of horror cinema. I say this because to this day Cassavetes — the actor, filmmaker and guiding force of the American Independent Film Movement — is still most commonly recognized by American viewers for playing Guy Woodhouse, the smirking, dishonest husband who allows Satan to impregnate his wife in exchange for a successful acting career, in Rosemary’s Baby (Polanski, 1969). To further fuel the horror movie fire beneath his legacy, recent reevaluations of Brian De Palma’s The Fury (1978) by cinephiles has caused Cassavetes’ head-popping final scene to become somewhat legendary; the clip of his bloody and explosive death at the hands of a telekinetic teenager still makes the rounds of “Film Twitter” in the form of a GIF and places regularly on “best death scene” lists.

Catch up on Split Tooth Media’s 31 Days of October Horror

Anyone familiar with Cassavetes as a director will recognize that horror movies in general stand in stark contrast to his personal philosophy on filmmaking and art. Throughout his career, he positioned himself as averse to the idea of film as entertainment or escapism; he whole-heartedly didn’t believe in it. He hated the physical violence found in the work of his contemporaries — from the bombastic shootouts in Bonnie & Clyde (Penn, 1967) to the brutal rapes in A Clockwork Orange (Kubrick, 1971) — that critics believed to be so edgy and groundbreaking. Cassavetes’ own films dealt in what he called “emotional violence.” Films like Faces (1968), A Woman Under the Influence (1973) and Love Streams (1984) are harrowing explorations into the lives and identities of himself and his actors that were unlike anything put out by Hollywood then or now. The goal during his productions was to render the divide between actor and character almost indistinguishable. He believed that the emotions of his actors and his audience were not something to play with.

Cassavetes saw the diversion presented by most movies, particularly American ones, as fundamentally exploitative not only for audiences, but for the actors starring in them. Cassavetes’ actual performances in films like Rosemary’s Baby and The Fury were often overshadowed by the on-set turmoil he could create when he didn’t feel challenged by a role or by his director. His fights with Polanski — who he saw as a poor collaborator and a control freak — remain legendary; his snarky stage whispers on the set of De Palma’s ludicrously stupid psychic film are well-documented (“She thinks she’s playing Joan of Arc,” the actor remarked aloud when Amy Irving asked for a break to think about her character’s motivations). Cassavetes understood, like few others, just how vulnerable of a position actors are placed in on a film shoot. Acting under the self-styled auteur Polanski and movie brat De Palma, Cassavetes had little room to explore his roles. He recognized that he and his fellow castmates were mostly there to say lines, take their clothes off and get killed while the camera did most of the work. He found these projects degrading. It was only through subtle acts of rebellion that he could make the productions worth his while. For instance, when he isn’t stuck playing second fiddle to a shirtless, gun-toting Kirk Douglas or combusting in front of De Palma’s bevy of cameras in The Fury, he is making odd, unexpected choices that unsettle the mostly formulaic film. As noted in Ray Carney’s Cassavetes on Cassavetes (2002), he decided to use a soft voice during his most menacing scene. He also put his arm in a sling to give himself something to work with beyond the script devoid of substance.

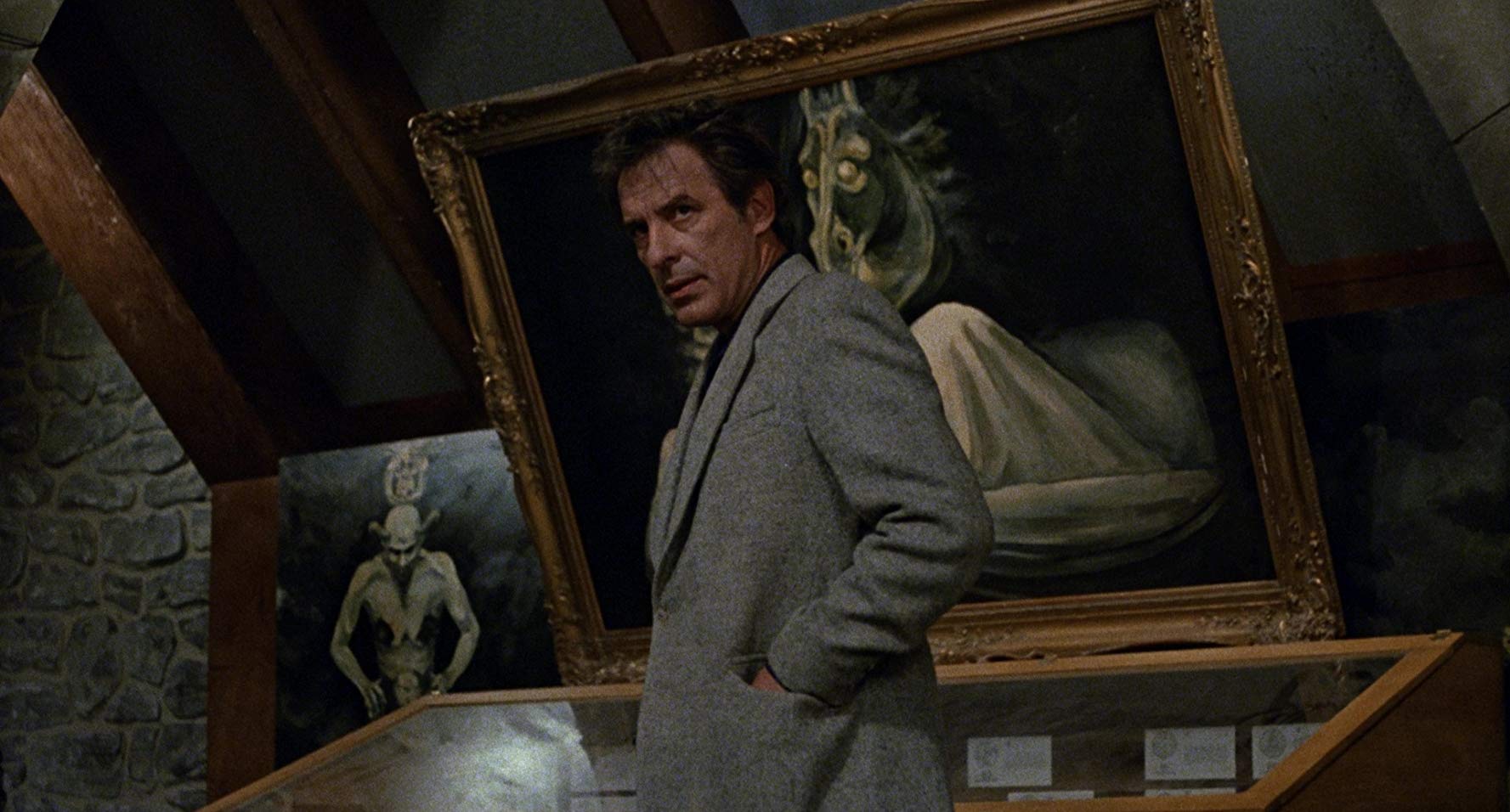

Based on his mostly negative experiences in horror films, it is strange that The Incubus (1981) — a low-budget Canadian supernatural slasher film Cassavetes starred in — is barely a footnote in most accounts of his life and career. Unlike Rosemary’s Baby or The Fury, The Incubus appears to be a project that he took closer to heart than many of his other acting jobs. In the film, Cassavetes plays Sam Cordell, a doctor in a small New England town that suffers an influx of rapes and murders. His daughter (Erin Noble) is dating a boy (Duncan McIntosh) who believes he is dreaming the murders into existence. Cordell feels compelled to investigate, with the help of a beautiful reporter (Kerrie Keane), as his autopsies are turning up strange results regarding the excess of red sperm found in all of the victims. The film eventually reveals that the town is being terrorized by a shape-shifting Incubus.

More October Horror: Joel Potrykus’ Midwestern Monsters Pt. 1: Ape and Buzzard by Bennett Glace

In general, The Incubus is a rather insignificant film in Cassavetes’ oeuvre as an actor. It doesn’t boast a big name director like Polanski; it didn’t fare well in the press (Vincent Canby said of the film, “Movies like this aren’t totally worthless. They provide employment for a number of people.”) and Cassavetes’ performance is far from his best. To be as clear as possible, I make no claims that The Incubus is a great film. It ranks leagues below Cassavetes’ own work as a director and his acting is nowhere near the greatness he achieved in Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky (1976) or even “Étude in Black,” the 1972 Columbo episode in which he steals the entire show as a murderous conductor. But as far as trashy horror films go, The Incubus is pretty darn good. Following the 2018 release of a Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray restoration of the film, The Incubus has benefitted from a minor reevaluation by horror fans. Originally written off by most viewers as a strange and “disturbingly nasty” film, a new generation of viewers have realized that the film has a little more to offer than was originally gleaned upon its release. And for Cassavetes, an actor who saw the joy of filmmaking not in the finished product, but for being a collective process shared among fellow artists, his time on the set of Incubus was a much more positive and active endeavor than most of the other films he acted in to fund his personal filmmaking endeavors.

****

“When you’re forced to play a part you don’t believe in, what you do is make it better. You make it better individually. In other words, you go on the thing, and if you don’t like your part, you argue about your part, or you find a better way than arguing… An actor is a very loyal person to life, a person who fights against all odds to make something work and doesn’t want to be fed a lot of lies.”

— John Cassavetes in Cassavetes on Cassavetes, Carney

Cassavetes could use his disdain for escapist filmmaking to turn in interesting performances in otherwise generic roles. This was a trait that could be noticed even back in his early days (notably the 1958 Western Saddle the Wind), with Cassavetes playing against the patterns of a film, creating space for himself to act while the surrounding cast stuck rigidly to the script. He could find the absurdity in treating formulaic material so seriously, much like the way he directed certain actors in his films Shadows and Husbands to “act badly” — with over-the-top, show-offish gestures and melodramatic flourishes — in order to portray a dishonest, insensitive or unimaginative identity.

In The Fury and The Incubus, Cassavetes is the scariest part of both films. He’s only the villain in one of them. He plays Sam Cordell as a troubled widower with a murky past. He has moved to a new town with his daughter and they mostly keep to themselves. His performance is shrouded with a nearly paranoiac desire for privacy; he hides a lot behind those heavy brows. Cordell has dreams that hint toward a potentially violent past with women, and it should be noted that most of Cassavetes’ co-stars — none of who knew how the film was going to end until it was shot — were shocked to find out his character wasn’t the Incubus considering the sinister way he played his “hero” character. His performance recognizes that horror is more about setting a strange tone than following a narrative.

The most important aspect that sets The Incubus apart from his other forays into the horror genre is that Cassavetes was able to use his top-billing to surround himself with people he trusted as collaborators. John Hough (Watcher in the Woods, Twins of Evil), who the actor previously worked with on the speculative WWII drama Brass Targets (1978), was brought in to direct at Cassavetes’ insistence. Recent sources, found on the Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray, tell of a production with an energy similar to those of Cassavetes’ own films. According to multiple accounts, Hough and Cassavetes worked together to rewrite most of George Franklin’s Incubus script (without taking any credit) before shooting began. Actress Kerrie Keane recalls that entire scenes would be rewritten day-of by Cassavetes and Hough. Hough remembers it differently, stating that Cassavetes was the force behind any script changes.

While it is unclear what specifically was changed or added to the script, certain elements of the final film ring very true to core themes and dramatic conflicts found throughout Cassavetes’ work. For instance, when Sam talks to his daughter about his second marriage to a much younger woman, he describes it as being plagued by infidelity on her part and jealousy and humiliation on his, many of which were issues he wrestled with not only in his personal life, but in nearly all of his films reaching from Shadows, his first, to Love Streams, his last personal project before his death. At certain points, dialogue in the film resembles the type of critiques Cassavetes would hear relating to his own filmmaking. A hyper-rational police officer tells Cordell to not let the situation “get supernatural,” in a tone that sounds like something a producer would have said to chastise Cassavetes during one of his troublesome studio-funded projects, like, “Don’t let this get artistic.” To convey the feeling on set, Hough has said that Cassavetes “made the whole situation rise up.”

The making of his own films could be physically and spiritually exhausting for everyone involved, but Cassavetes often cultivated an atmosphere of comradery through collective artistic risk-taking. The Incubus shoot was similarly lively and collaborative, albeit with lower artistic stakes. The actors speak of the production being almost surprisingly spontaneous and improvisational considering the material. Keane says that Hough and Cassavetes created an environment that encouraged “rolling with it.” Whether or not Hough helped Cassavetes with the script rewrites, he helped cultivate the openness that Cassavetes brought to the project. Cassavetes was given room to explore his character in ways he was unable to in his previous horror efforts. He did his research for the role by spending time with doctors and found many of them to be troubled figures who treated the job as an escape from their personal realities. He plays Cordell with a haunted detachment to the cadavers placed in front of him. A particular scene of note involves Cassavetes inspecting a corpse, examining the body and becoming lost in thought as he takes off his surgical gloves by flinging them across the room as his eyes seem to wander into another scene.

Fun was had as well. Apparently, during a particularly goofy scene, in which the script called for Cassavetes to use the phrase “three-pronged sperm,” he and co-star John Ireland could not keep from laughing, no matter how many takes they did. Hough pretended to be mad at them, breaking the shoot for lunch in order to make them think they were in trouble. They came back to the set only to find that the line had been cut.

Cassavetes also found ways to carry the creative spirit he developed with his fellow actors on set over into their off-hours. Keane recalls being called to Cassavetes’ hotel room one night, where she ended up playing the part of Mabel during an impromptu script reading of A Woman Under the Influence with Gena Rowlands and Ben Gazzara, whom Cassavetes had called in for the weekend. To further decrease the lack of distance between art and real life, she says the actor would host dinners at local restaurants that would resemble scenes out of one of his films — wine would flow and the table would transform into an event not unlike the spaghetti breakfast scene Mabel stages with her husband’s work friends. Keane says that Cassavetes wanted everyone to be included.

Immediately after wrapping the film in Toronto, Cassavetes was off to Boston the next day to start shooting Whose Life Is It Anyway? (Badham, 1981), coincidentally another film where he plays a doctor. He often said he didn’t care so much about finishing his films. If he could have, he never would have left many of his own productions. What he was interested in was the actual work — the interactions, the disagreements, the last-minute changes, the mistakes, the struggles that lead to new ways of understanding through writing, acting, directing and editing: in other words, each and every stage of the filmmaking process. The Incubus is certainly a film that would have meant more to him as a process than as fodder for his acting resume. But for all it’s worth, he was able to raise a would-be forgettable ’80s horror film to where his collaborators were challenged to think beyond what was required of them, helping to build an environment where, as Keane says, “knowing why” wasn’t important; it was a matter of reaching beyond the basic narrative and into the emotional core of the film.

Find the complete October Horror Archive here:

Purchase The Incubus on Blu-ray/DVD from Vinegar Syndrome or Amazon

Follow our list of the 31 Days of October Horror on Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)