From one of the figureheads of the Cinema of Transgression, Richard Kern’s 1985 anthology film is a violent and sexually explicit nightmare tour through a degenerate New York City

Throughout the ’80s and early ’90s, Richard Kern made a series of “hardcore” short films that became definitive entries in the Cinema of Transgression. Produced in collaboration with members of New York City’s No Wave music and art scene, these films are bloody, violent, purposefully appalling and sexually disorienting in ways that make the work of fellow shockers like David Cronenberg look about as edgy as a Spielberg flick. Kern’s shorts are not horror films in any general sense, but they are often scarier than most films that aim to be. His music video for Sonic Youth’s “Death Valley ’69” (co-directed with Judith Barry) features bodies heaped across rooms, with guts streaming out of torsos and dismembered limbs strewn all about; in his famous collaborations with Lydia Lunch — “Fingered” and “Right Side of My Brain” — explicit sexual fantasies take severe turns into very real acts of brutality and deviancy. What’s more is that Kern and his collaborators often set a tone of sheer rapscallion glee in these nightmarish films. They have a “just for the hell of it” abandon that adds a comedic strain to the sinister acts taking place — a balance many filmmakers strive for yet few have sustained so effectively.

Manhattan Love Suicides (1985) is an anthology film collecting four of Kern’s shorts about lust, obsession and self-destruction in New York City. Featuring some of his best work, the anthology format highlights the range of Kern’s early style. The films explore many of his favorite themes through a variety of forms: There is a micro-narrative of a brutal artist-muse relationship (“Stray Dogs”); a story of a woman with a new car being overwhelmed by the men in her life (“Woman at the Wheel”); a domestic melodrama about a deformed drug-dealer and his lover (“I Hate You Now”) and a music video that builds to an absolutely despicable climax (“Thrust in Me”).

Like many of Kern’s films, these shorts are about characters at their breaking points. Personal anguish has become so overwhelming that it begins to wear down their composure and lead them towards displays of violence, self-mutilation and even physical decomposition. But more so than perhaps any of his stand-alone narrative shorts, these films show that Kern’s style could be horrifying in a way that goes beyond any of the blood or violent sexual acts on screen. Manhattan Love Suicides is scary in the way that many of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s tales are scary. A similar “black conceit” — Melville’s term for Hawthorne’s darker stylistic perversities — shows throughout Kern’s narratives. They take place in that strange romantic limbo between stark reality and allegorical fantasy, where desire and lust burn away at the hearts and minds of his characters. The dark fantasies set inside their heads are met with rejection from lovers and clash against the harshness of the cruel environments they find themselves trapped in. Of course, Kern trades out New England for a dirty NYC, Salem witches for gun-toting supervixens, and artists of the beautiful for nihilistic necrophiliacs. Notions of ideal beauty (“I Hate You Now” is roughly a reversal of Hawthorne’s “The Birth-Mark”) and socially forbidden love are flipped into the gutter as these street punks seek out pain, depravity and sin.

October Horror: What Ever Happened to Spider Baby?

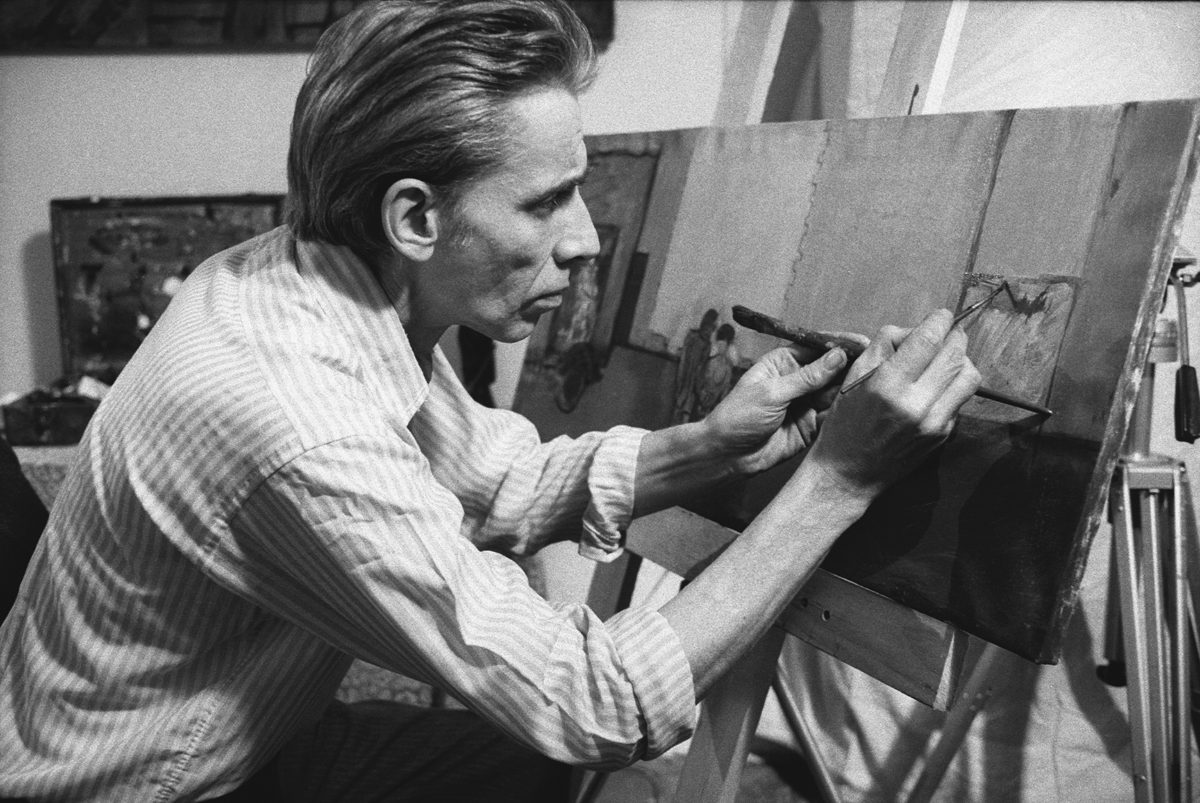

“Stray Dogs” immediately lets us know what kind of “love” to brace ourselves for. The short starts with The Artist (William Rice) casually walking down a NYC street with a beautiful woman on his arm. They cross paths with a man (played by artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz) who begins violently twitching upon recognizing the artist. Kern sketches these characters with a provocative lack of psychological detail, freeing the actors to reach for the most strained and extreme of emotions in their performances. The man begins following the couple like a zombie until the woman leaves and the two men end up alone together in the artist’s studio. Once inside, the artist begins to paint as the man tries to draw his attention. The artist scoffs at his twitchy admirer, who begins to masturbate while watching him paint.

Many of Kern’s films feature artists (often played by Kern himself) interacting with their models, exploring the complicated attractions and detachments that can develop between creator and subject when art gets involved. We learn that the man may have been one of the artist’s models — he finds a portrait of himself among a stack of photos of other men — who has grown a bit too attached. Continuing to struggle with being ignored by the indifferent man he desires, Wojnarowicz’s character starts to physically disassemble. Skin splits; veins spurt. But this doesn’t deter him, as he goes to the bathroom to freshen up, still trying to keep up appearances as his body deteriorates. The artist shows only annoyance and disgust as his guest’s limbs start to detach. It isn’t until he collapses into pieces on the floor that the artist pays any substantial attention to him by picking up a pad and pencil to sketch his death scene.

“Woman at the Wheel” makes the best use of Kern’s lo-fi aesthetics to build an urban hellscape around its troubled female character. Adrienne Altenhaus plays the owner of a new car. She picks up two different men who both shove her aside to take the driver’s seat. Over the course of the two brief trips, the film unfolds like an anxiety attack; the scenes in the car are framed to be claustrophobic as Altenhaus fights with both of her male companions. The out-of-sync dialogue drags against the images of its characters screaming at each other while speeding through city streets. At one point, the grainy black-and-white photography makes the reflection of trees flashing across the car’s windshield look more like flames engulfing the fighting couple than leaves and branches. Returning to the car with the second man, the woman bashes him with a glass bottle before snatching the keys to speed off. She eventually wrecks the car, but not before the film detours through a Carnival of Souls-style fever dream. The film abruptly cuts to a wide-open road. As she drives further, even her fantasies of escape become overrun by aggressive men jeering and forcing themselves upon her car. She begins to scream, but it only gets worse as an orgy breaks out in her backseat.

“Thrust in Me” parallels two highly melodramatic performances of extreme despair. Nick Zedd — author of the Cinema of Transgression manifesto — co-directs and stars in dual roles as a male punk and a woman contemplating suicide. Set to The Dream Syndicate’s “John Coltrane Stereo Blues,” the film is brutally simple. Any traces of background into the two Zedds and their states of degradation are absent. Viewers may benefit by approaching this film more along the lines of dance than as storytelling. Kern and Zedd explore each character’s dire emotional state through a series of brief encounters and interactions with props. The male Zedd reacts to his alienation by rejecting seemingly all notions of human decency. He stalks the city streets, staring down passers-by and violently intervening in a dispute between a man and woman on the sidewalk. The female Zedd sits in her apartment skimming through self-help books and Emile Durkheim’s Suicide. Eventually, she draws a bath, gently tears Jesus’ image off the cover of a Bible and tapes it on the wall above the tub. She then strips, sinks into the water and slits her wrists.

October Horror: George Romero’s Martin: Searching The Soul Of An Incel Vampire In 2019

When the male Zedd arrives at the same apartment, Kern stages the scene so that he repeats many of the same motions as his female counterpart. But he does so like a caged animal, throwing things and pacing around the room. He sits down to use the toilet and rips down the image of Jesus to wipe himself before noticing the corpse in the tub.

For as shocking as the finale may be — which I will refrain from describing — “Thrust in Me” stands out for how Kern builds such a menacing atmosphere out of little else than his actors’ performances. The city that the male Zedd walks through is shown to be a cruel and humiliating environment. When he engages in the sidewalk dispute, Zedd throws the man to the ground and moves along. Kern stays in the scene as the man looks up from the ground to his female sparring partner. Terror develops in his eyes as Kern cuts to a chilling close-up of the woman breaking out in vicious, uncontrollable laughter at his weakened position. In this brief, tangential moment, fear and hatred are expressed in their purest, most uninhibited forms. Through the simplicity of Kern’s narrative, “Thrust in Me” is able to reach for such terrifyingly primitive emotions along his characters’ paths to moral and corporeal oblivion.

October Horror: High Tension: Conflicting Fantasies of a Different Body

As mentioned, “I Hate You Now” explores similar territory to Hawthorne’s “The Birth-Mark.” Hawthorne’s story is about a scientist who tries to remove a birthmark from his wife’s face to perfect her beauty, ultimately killing her in his attempts. Kern creates a tale not of someone seeking to remove a blemish, but scarring themselves to match a partner’s deformities. The film begins with a rather violent sex scene between Amy and Tommy Turner before Kern establishes a strange but loving domestic normalcy for the couple in their apartment. Tommy goes to lift weights while Amy fixes eggs for breakfast. Not unlike the way Paul Morrissey introduces Joe Dallessandro’s hustler character in the first act of Flesh (1968) — in bed with his wife and playing with his baby at home before he leaves to turn his daily tricks — it isn’t until breakfast is served that Tommy is revealed to be a drug dealer with a severely deformed face. He goes to sell drugs on a street corner, leaving Amy alone to do chores around the house. She reflects romantically upon Tommy and his scar while ironing clothes, staring into the hot metal iron before smashing it into her face.

It’s clear that Amy’s attempt to reproduce her lover’s distinctive mark upon herself was done as an act of unabashed affection. But when Tommy comes home, he sees his own disfigurement unnaturally replicated upon Amy. In a fit of passion he kills himself by crushing himself with his barbells. “You have aimed loftily!” says the scientist’s wife in “The Birth-Mark” as she perishes from his experiments. “With so high and pure a feeling, you have rejected the best that earth could offer.” Amy’s feelings were, while maybe not “high,” quite “pure,” in their own unique, Kern-like way. But like the scientist, her action was fueled by a delirious romanticization of superficial aspects and appearances, blinding her to the rather idyllic relationship she and Tommy shared without wearing matching scars. And of course, the inevitable shift from lofty romance into tragedy is a severe and grisly one.

Kern has moved away from the brutal style of his earlier films. He now mostly works with young, nude models. But in his early “hardcore” years as a filmmaker, he found an ideal form in the anxious dirges of Manhattan Love Suicides. The primitive narratives, disturbing actions and melodramatic extremes lead to moments that are as overwhelmingly beautiful as they are transgressive and terrifying. Perhaps there is no better example of this than in the final shot of “I Hate You Now” — the film’s poster image — as Amy Turner sets herself on fire in a cartoonishly tiny frying pan. The image, for all of its flamboyance, is about as raw of a display of romantic despair as the human mind can conjure. As Turner writhes around in superimposed fire, mascara streaming down her face, the gritty black-and-white Super 8 film stock looks like it is going to disintegrate along with her. The image is the cinematic equivalent of a primal scream.

Purchase Kern’s “Hardcore” films on Blu-ray direct from his website

Find the complete October Horror Archive here:

Find the complete 31 Days of October Horror list here

Follow Brett and Split Tooth Media on Twitter

Follow our list of the 31 Days of October Horror on Letterboxd

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)